![]()

"There is Magic in Print": The Holiness-Pentecostal Press and the Origins of Southern Pentecostalism

Randall J. Stephens/The University of Florida

I believe the dear Southland will receive [a] great blessing this time. She is ripe for it. I pray that she may not miss it . . . .

—Frank Bartleman

I am so glad of all God is doing in the South-land and am pleased to put my name on record for all [Pentecostalism] stands for. I received the Baptism of the Holy Ghost at Azusa St., Los Angeles, Cal., on July 2, 1906. My heart has been overflowing with His sweet peace and love ever since.

—Mary Radabaugh

Testimonials similar to these flooded holiness and pentecostal periodicals throughout the United States from 1906 to 1910, making the religious press instrumental in the revival's formation and perpetuation. As correspondents penned their sentiments, Pentecostalism entered the South through the enthusiastic reports of an unconventional revival occurring in Los Angeles.(1) William Seymour, an African-American holiness preacher originally from Louisiana, began his revival with integrated meetings in a run-down former A. M. E. church on Azusa Street. Soon after the revival began in April 1906, the gatherings received the attention of Los Angeles Times reporters, who lampooned the attendants for their religious excesses. The spiritual acrobatics performed at the Azusa mission—including jumping, dancing, falling prostrate on the floor, shouting, speaking in tongues, and prophesying—made its participants easy targets of ridicule. One L. A. Times reporter denigrated the meeting as a "Weird Babel of Tongues." The writer mercilessly parodied Seymour: "An old colored exhort, blind in one eye, is the major-domo of the company. With his stony optic fixed on some luckless unbeliever, the old man yells his defiance and challenges an answer." The press, whether positive or negative, helped spread Pentecostalism far beyond the confines of L. A. Subsequently, Frank Bartleman, a major leader at Azusa, claimed the L. A. Times gave "us much free advertising" and made thousands aware of the revival who otherwise would never have come in contact with it.(3)

|

|

|

| "These papers described the interracial worship taking place at Azusa and highlighted the prominent roles of women in the revival." | |

|

|

The press, secular and sacred, became essential in promulgating the movement in the states and abroad. Yet, scholars have written so little on the origins of Pentecostalism in the South that the role of the press in these early years received scant attention.(4) At least two factors make this religious movement significant in larger cultural terms and worthy of critical study. First, by sheer numbers of adherents Pentecostalism is arguably the most important mass religious movement of the twentieth-century.(5) Secondly, southern pentecostals, at least in the first few years of the movement, frequently transgressed racial and gender hierarchies in a region dominated by Jim Crow and intense patriarchalism.

Historians of southern religion have clearly demonstrated the massive impact of evangelicalism on the region.(7) But Pentecostalism in particular has seldom been investigated. Consequently, many questions about the origins of this movement remain unanswered. Currently we do not know why Pentecostalism proved so successful in the South, often overshadowing other sects and mainline denominations.(8) It is also still somewhat unclear how the doctrine and practice of the southern holiness movement served as catalysts for the new sect. Moreover, it would be helpful to determine the degree to which southern pentecostals were in fact dissenters from prevailing racial and gender conventions. The holiness and pentecostal press sheds considerable light on these matters, and offers some clues as to how pentecostals imagined their religious community and transmitted and sustained their counter-cultural vision.

|

Grant Wacker, the preeminent historian of American Pentecostalism, argues that periodicals "constituted by far the most important technique for sustaining national and world consciousness" among pentecostals.(9) Much like earlier revivals in America, the press defined and invented the movement, unifying its discourse and orienting it along communal lines.(10) Without question other forms of communication, including the preached word, pamphlets, broadsides, and books, were also critical to the spread of southern Pentecostalism, but in the earliest period the press was more crucial. The immediacy of newspapers and the ways in which they allowed individuals throughout the U. S. to correspond with one another made them an unusually potent medium. Roughly three-quarters of a century before the Pentecostal Revival Alexis de Tocqueville piercingly observed, "Only a newspaper can put the same thought at the same time before a thousand readers."(11) And holiness as well as pentecostal adherents distinguished themselves as avid readers of religious books and papers. W. B. Godbey, one of the most influential southern holiness authors and evangelists, perfectly summed up his co-religionists' sentiments. "[L]et us remember that there is magic in print," he wrote in his autobiography, "rendering it far more influential than words spoken . . ." Spoken words, thought Godbey, faded away soon after they were uttered, but the printed word could last indefinitely and influence far more individuals as a result.(12) Though many scholars describe pentecostal religious culture as fundamentally oral-based and anti-modern, from the beginning believers relied heavily on print culture and shrewdly manipulated modern technologies.(13)

A paper published from the Azusa Street mission, The Apostolic Faith, and a barrage of other holiness periodicals served as springboards for southern Pentecostalism.(14) They were the primary agents through which the emerging pentecostal community first imagined itself.(15) Within their pages, radical holiness people wrote and read about the restoration of New Testament gifts occurring in Los Angeles.(16) These papers described the interracial worship taking place at Azusa and highlighted the prominent roles of women in the revival. They also covered the gift of speaking in tongues, not a feature of the holiness movement, and convinced many holiness adherents that the more zealous pentecostals were the rightful bearers of gospel truth. As editors tantalizingly described the strange new "gifts of the Spirit" manifested at Azusa, they also provided space for elaborate testimonies. Men and women, some barely literate, from Tennessee, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi wrote to the papers and expressed their hunger for experiences equal to those occurring in the West.(17) Accordingly, the reportage on the Azusa revival persuaded southern holiness leaders like the white evangelist Gaston Barnabas Cashwell and the African-American minister Charles Harrison Mason to make pilgrimages to Los Angeles in search of their "Pentecost" and the baptism with the Holy Ghost.(18) The revival that began in California spread rapidly into the South, prompting A. J. Tomlinson, the first general overseer of the Church of God (Cleveland), to apply the well-worn incendiary metaphor to this region: "The Fire is spreading for miles and miles in every direction."(19)

The newspaper accounts that followed the Azusa revival were the culmination of a movement steeped in a long tradition of theological perfectionism and religious radicalism. And although Pentecostalism was a relatively new religious sect in the early twentieth century, its roots were firmly planted in the Holiness Revival of the late nineteenth-century.

As early as 1867, a new agency led by northern Methodists, the National Camp Meeting Association for the Promotion of Holiness, began disseminating holiness doctrine in revivals throughout the North. These holiness advocates disapproved of the alleged impiety of mainline denominations. They also despised the growing wealth, smugness, and elaborateness of their churches. Lower and middle-class communities throughout America expressed in religious terms the same discontent that motivated the Populist movement.(20) Dissatisfied with the churches of their youth, they formed new religious communities committed to the theological doctrine of perfectionism.(21) These former Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists were convinced that the Holy Spirit had descended. They traced its origins to the early church as revealed in the book of Acts. Hence, the Holiness Revival produced zeal for "Spirit Baptism" (a divine empowerment of believers) and for other gifts of the New Testament church, such as healing and prophecy.(22)

Already by the late nineteenth-century the National Camp Meeting Association had introduced many southerners to perfectionism. In September, 1872 this organization held it's first meeting below the Mason Dixon line. John Inskip, president of the organization, and other northern evangelists who officiated had reason to be cautious in the post-war South. However, the Knoxville Daily Chronicle assured its readers that holiness promoters knew "no North, no South, no East, no West," but were motivated by one goal, the propagation of holiness. Some Tennesseans remained unconvinced, imagining these northerners to be paid agents of the government with more sinister designs.(23) This suspicious faction proved the minority. Most of the roughly six thousand congregants in attendance at Knoxville and other later revivals eagerly received the doctrine of entire sanctification, a second work of grace following salvation, in which, they thought, the believer was made free from sin. At subsequent camp meetings throughout the region such colorful southern evangelists as "Uncle" Bud Robinson, L. L. Pickett, Beverly Carradine, Mary Lee Cagle, H. C. Morrison, John Lakin Brasher, and W. B. Godbey drew thousands of new recruits into holiness ranks.

Editors and corespondents in newly established holiness papers wrote of their commitment to perfectionism. Accordingly, the Virginia-born evangelist G. D. Watson expressed the perfectionist sentiment in his periodical Living Words (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), arguing that anyone "born of God doth not commit sin." Other initiates believed that when they were entirely sanctified God removed their "carnal mind," cleansing them of "all sin."(24) Soon readers mastered the nomenclature and practice of this doctrine.

These papers exercised power over converts' lives in numerous other ways as well. Widely circulated holiness periodicals such as The Christian Alliance and Missionary Weekly (New York), The Firebrand (Shenandoah, Iowa), The Gospel Trumpet (Anderson, Indiana), The Way of Faith (Columbia, South Carolina), Zion's Outlook (Nashville), The Holiness Advocate (Lumberton, North Carolina), The Way of Life (Cartersville, Georgia), and Live Coals (Royston, Georgia) told black and white adherents which books to read, which evangelists to follow, who and what to pray for, and which doctrines to accept or reject.(25) Papers regularly featured full-page advertisements for holiness literature available at reasonable prices. Editors sold the works of authors from the Wesleyan canon—John Wesley, John Fletcher, Madam Guyon, and Adam Clark—as well as texts by newer lights who reshaped Wesleyanism—Phoebe Palmer, Daniel Steele, W. B. Godbey, S. A. Keen, and G. D. Watson.(26)

The holiness press also created a strong sense of fellowship, even where no physical community existed. Spread out across the South, many holiness people could not actually attend the various revivals reported throughout the region. But within the pages of their newspapers, they entered an imagined community which united them even as they were apart. In an 1899 issue of Live Coals of Fire, one initiate from Hartwell, Georgia wrote that after reading testimonies and reports of the "warfare of God" in this paper he felt as if he were in the midst of a "red-hot testimony meeting." Furthermore, he believed that if he did not write to the paper to testify about his own experience, he would somehow lose the fullness of his faith. A Mobile, Alabama judge named "Price" experienced something similar. For years he subscribed to northern holiness papers like The Christian Standard and knew the names and read the editorials of a host of holiness preachers. Yet he never met any of these in person.(27) Converts all over the South held the same feelings of community and solidarity.

Devotion to the new holiness periodicals ran high. Many readers announced that they would only read holiness newspapers, leaving secular and denominational publications to "worldlings." Methodist officials fumed at the exclusiveness of the new craze. One holiness believer wrote to the journal of the South Carolina conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South to announce the cancellation of his subscription. "Dear Brother: Please stop my ADVOCATE, as I take The Christian Standard and Way of Life," he bluntly stated. The Methodist editor thought this gentleman's disloyalty incredible and rebuked him and other holiness enthusiasts who looked for spiritual sustenance outside the confines of official southern Methodism.(28)

|

|

|

| "As editors broadcast their peculiar social beliefs in newspapers scattered throughout the region, southern stalwarts constructed a counter-cultural environment that would easily be accommodated within the domain of Pentecostalism." | |

|

|

As holiness folk met with opposition among mainline groups, they found other ways to spread their message. Numbers of converts, eager that more might know about entire sanctification, circulated their older holiness newspapers among friends and neighbors. Some believed so whole-heartedly in the mission of holiness periodicals that they became ardent newspaper agents, selling or giving out copies at revivals, local stores, and on street corners.(29) Miller Willis, an eccentric evangelist based out of Georgia, even worked out a program of holiness print evangelism. He suggested to the readers of The Christian Witness (Boston, Massachusetts) that they start up holiness circulation libraries in their churches. Once holiness proponents won over their congregations they should introduce a "good holiness paper" to them and "get it into as many homes as you can." Willis found too that reading extracts out of holiness books and papers from the pulpit yielded tremendous results. Like Willis, Irving E. Lowery, an African-American minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church of South Carolina, aggressively pitched holiness newspapers. In the pages of The Christian Witness he urged black ministers of the South Carolina conference to take this northern holiness journal. At the Kingstree, South Carolina conference meeting in 1887 he gave away 110 free copies of The Christian Witness in an attempt to entice new subscribers.(30) Pentecostals, as will be shown later, would express an equally zealous devotion to their periodicals.

Two radical holiness papers in particular, The Pentecostal Herald (Louisville, Kentucky) and God's Revivalist (Cincinnati, Ohio), were perhaps most instrumental in the transition from holiness to pentecostal. Though one paper was published in a border state and the other in a northern one, both exerted profound influence upon the South. These papers represented the translocal holiness movement as a whole by eschewing geographic as well social boundaries.(31) In the 1890s and early 1900s, scores of soon-to-be southern pentecostals corresponded with both publications, seeking advice, offering their viewpoints, and reporting on local revivals.(32) The Pentecostal Herald received letters from holiness proponents in all the former Confederate states. Though exact figures are difficult to obtain, it is clear that The Pentecostal Herald and God's Revivalist maintained large circulations. In 1893 The Pentecostal Herald held a circulation of 15,000, 30,000 in 1920, 38,000 in 1934, and 55,000 in 1942. In just one week in early 1898, the Herald gained 1,078 subscribers. Nearly as successful, The Revivalist reported 20,000 copies circulated monthly by the Summer of 1899.(33)

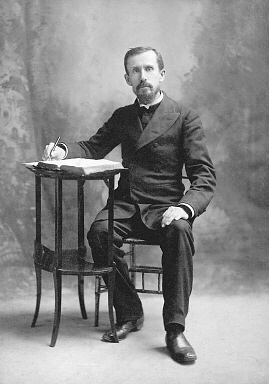

The editors of these publications vigorously spread the message of holiness, which they considered essential to any vital Christian's life. Pentecostal Herald editor, Henry Clay Morrison, would be motivated by a single-minded enthusiasm. Laying in bed one night in 1888, Morrison felt that if he could multiply himself into a "score of men," he could widely disseminate his holiness message. At this point he struck on the idea of publishing a paper. It might do the work of hundreds of preachers, reasoned Morrison. He envisioned the paper would inspire a return to plain folk religion and the "old paths" of Methodism. Morrison possessed no experience in newspaper publishing, but that seemed inconsequential to him. Small presses cost as little as $125 dollars and paper and supplies were also relatively inexpensive. Taking advantage of increasingly low-cost equipment and materials, others too soon established presses dedicated to holiness and radical religion.(34)

|

The aptly titled God's Revivalist, edited by the impassioned Martin Wells Knapp, claimed to be under the sole proprietorship of God, published in "His" interests. In this paper, Knapp employed pentecostal language that well foreshadowed the hyperbolic vocabulary of the tongues movement. Using apocalyptic imagery, Knapp published accounts of "Revival Dynamite," "Revival Tornados," "Lightning Bolts from Pentecostal Skies," and "Revival Fire."(35) Southern holiness folk were electrified by Knapp's paper and others like it. Between 1893 and 1900 twenty-three new holiness sects emerged in the South. And from the Methodist Church alone the exodus of members numbered roughly 100,000.(36)On a practical level, radical holiness commitments precluded participation in secular entertainments, such as theater going, attending sporting events, or social dancing. The faithful frequently prohibited the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, coffee, Coca-Cola or anything else that "'blunted' one's 'moral quality.'"(37) As editors broadcast their peculiar social beliefs in newspapers scattered throughout the region, southern stalwarts constructed a counter-cultural environment that would easily be accommodated within the domain of Pentecostalism.

The scrutiny which holiness groups applied to mainline churches was as demanding as their opposition to popular culture. Within the pages of their periodicals they held their churches accountable for any delinquency in doctrine or morality. Editors and correspondence lamented the growing indifference or outright opposition to perfectionism in mainline churches. Speaking of the late nineteenth-century, the ardent Church of God evangelist J. W. Buckalew bemoaned: "Mr. John Wesley said when the Methodist church gave up the doctrine of holiness they would be a backslidden and fallen church. They have surely given it up for the people have quit getting their [sanctification] experience."(38)

At the same time holiness folk battled doctrinal declension, they resisted the growing embourgeoisiement of Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches. Subsequently, they reacted against mainline churches and the "diversion of enthusiasm from the salvation of souls to the building of institutions," as one historian put it.(39) Because increasingly formal mainline churches could not accommodate the needs of their poorer members, many made the departure into more ecstatic, unconventional holiness churches. Once settled in the new sects, members felt free to act and dress as they pleased. According to Mickey Crews, the predominately rural Church of God (Cleveland) became a counter-cultural bulwark against its social betters. Many southern holiness papers denounced eating pork, the wearing of neckties for men and fashionable dresses or jewelry for women. They also opposed contemporary attitudes toward recreation, status, and race.

Holiness and later pentecostal churches were the most integrated religious bodies in the South. Hence, God's Revivalist frequently corresponded and supported African-American holiness evangelists like Amanda Berry Smith. Occasionally the paper included features hinting at an openness to integrated services. In 1901, a published letter to the Revivalist asked the question of whether blacks and whites worshiped together in biblical times. Kentucky-based evangelist W. B. Godbey answered emphatically, yes, offering proof texts to back up his position.(40)

There is Magic in Print, Part II

|

The author wishes to thank the following

for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article: Fitzhugh

Brundage, David Hackett, Matt Harper, Ben Houston, Charles E. Jones, Susan

Lewis, Donald G. Mathews, David Roebuck, Beth Stephens, Grant Wacker,

Brian Ward, David Harrington Watt, Bland Whitley, Daniel Woods, and Bertram

Wyatt-Brown.

|

NOTES

2. The term Holiness-Pentecostal denotes the interlocking networks and similar religious outlooks of the two movements. The doctrines of a second, purifying work of grace (usually called entire sanctification), the baptism of the Holy Spirit, and the premillennial second coming of Christ were important to both. Although Pentecostalism and speaking in tongues arose after 1900, Pentecostalism had its origins in the Holiness revival of the 1880s and 1890s. Donald W. Dayton, Theological Roots of Pentecostalism (Metuchen, New Jersey and London: The Scarecrow Press, 1987), 87-113. To distinguish Holiness from Pentecostal churches in the U. S., J. Gordon Melton asserts that the Pentecostals, unlike the Holiness people, seek and receive "the gift of speaking in tongues as a sign of the baptism of the Holy Spirit." J. Gordon Melton, The Encyclopedia of American Religions, Vol. 1 (Tarrytown, New York: Triumph Books, 1991), 41.

3. Los Angeles Daily Times, 18 April 1906, sec. II, p. 1. Ibid., 19 April 1906, part II, p. 4. Los Angeles Herald, 10 Sept 1906, p.7. Ibid., 24 September 1906, p. 7. Topeka Daily State Journal, 25 July 1906, p. 6. St Louis Post Dispatch, 2 August 1906, part II, p. 11. Frank Bartleman, Azusa Street (South Plainfield, New Jersey: Bridge Publishing, Inc., 1980), 48.

4. Southern historians, in general, have failed to take into account the impact of Pentecostalism in the New South. Donald Mathews points out that before Edward Ayers' The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), "the major synthesizers of southern history," including U. B. Phillips, William Dunning, C. Vann Woodward, George Tindall, Wesley Frank Craven, and E. Merton Coulter, had "not been forced to explain the role of religion in southern life." Donald G. Mathews, "'We have left undone those things which we ought to have done': Southern Religious History in Retrospect and Prospect," Church History 67 (June 1998), 306.

5. Pentecostalism has failed to attain scholarly attention commensurate with its size. Today, Pentecostalism is the second largest sub-group of global Christianity. It claims approximately eleven million American adherents and a worldwide following of more than 430 million.(6)

6. Grant Wacker, "Searching for Eden with a Satellite Dish: Primitivism Pragmatism and the Pentecostal Character," in Religion and American Culture, David G. Hackett, ed. (New York and London: Routledge, 1995), 440. Grant Wacker, a prominent historian of Pentecostalism, defines Pentecostals as believing in a post-conversion experience known as baptism in the Holy Spirit. Pentecostals, he says, believe that a person who has been baptized in the Holy Spirit will manifest one or more of the nine spiritual gifts described in 1 Corinthians 12 and 14. Ibid., 441.

7. David Edwin Harrell suggest that if southern religious experience is not qualitatively distinct, it is, nonetheless, quantitatively different from that of other sections of the U. S. The South has been the most solidly evangelical section of the country. According to Harrell, excluding "the Mormon havens in Utah and Nevada, the most homogenous religious states in the nation are in the South. The Bible Belt was a well entrenched stereotype by the early twentieth century, and it was one with clear substance to it." This region, remarks Harrell, "was a reservoir where the old-time message had remained intact amid the challenges of the twentieth century." David Edwin Harrell, "Introduction," in Varieties of Southern Evangelicalism, ed. David Edwin Harrell (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1981), 2, 3. Samuel Hill asserts that although secularization has grown in the recent South, it "scarcely made a dent in the fabled religiosity of the southern people . . ." Samuel S. Hill, "Introduction," in Varieties of Southern Religious Experience, ed. Samuel S. Hill (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 3. Ted Ownby argues that the South can be rightfully called an evangelical culture "if we realize that people who rarely attended church and who lived far outside the evangelicals' moral code nevertheless found ways to express their beliefs in the virtues of the dominant religion." Revivals, Ownby suggests, became the locus where sinners as well as saints expressed their commitment to southern Christian culture. Ted Ownby, Subduing Satan: Religion, Recreation, and Manhood in the Rural South, 1865-1920 (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 162.

8. We currently know little about how mainline denominations and local communities responded to the supposed threats these groups posed. Vinson Synan, The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century (Grand Rapids and Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1997), 66-67.

9. Grant Wacker, Heaven Below, 264. At a 1915 convention of the Pentecostal Holiness Church, leaders of the denomination recognized this all important aspect. They reported: "There is perhaps no agency among us greater than the printing press. Hence, we are admonished by the Word of the Lord to give attendance to reading . . ." F. L. Bramblett, D. R. Brown, and Hugh Bowling, "Report of Committee on Books and Periodicals," in Minutes of the Fifth Annual Session of the Georgia and Upper South Carolina Convention of the Pentecostal Holiness Church Held at Canon, Ga., Nov. 17-19, 1915 (n.p., 1915), 8-9. In the late nineteenth century the newspaper industry experienced extremely rapid growth. Between 1870 and 1900 the number of daily newspapers quadrupled while the number of copies sold daily increased nearly sixfold. Michael Emery, Edwin Emery, and Nancy L. Roberts, The Press in America: An Interpretive History of the Mass Media (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2000), 157. Technological advancements, including the development of high-speed presses, the invention of the typewriter, and the shift from rag to wood-pulp paper, greatly contributed to this boom. George H. Douglas, The Golden Age of the Newspaper (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1999), 83-86. Kevin G. Barnhurst and John Nerone, The Form of the News: A History (New York: The Guilford Press, 2001), 105-106. I would like to thank David G. Roebuck for alerting me to the importance of these changes.

10. For an examination of how the press imagined the First Great Awakening, see Frank Lambert, Inventing the "Great Awakening" (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999), 87-124; Harry S. Stout, The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1991), 113-132; and T. H. Breen, "Retrieving Common Sense: Rights, Liberties and the Religious Public Sphere in Late Eighteenth Century America," in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty: Rights in American History, ed. Josephine F. Pacheco (Fairfax, Virginia: George Mason University Press, 1993), 55-65. On the role played by the press in the Third Great Awakening, see Kathryn Long, The Revival of 1857-58: Interpreting an American Religious Awakening (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 26-45. Long reveals that "Although the Reformed clergy shaped the narrative of the 1857-58 Revival for later historians, newspapers told the story to most Americans in the spring of 1858." Religious and secular papers emulated each others' writing styles and helped organize and unify the language used to describe the event. Ibid., 27.

11. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. J. P. Mayer (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1969), 517.

12. W. B. Godbey, Autobiography of Rev. W. B. Godbey, A. M. (Cincinnati, Ohio: God's Revivalist Office, 1909), 10.

13. On the orality of holiness and pentecostal culture, see J. Lawrence Brasher, The Sanctified South: John Lakin Brasher and the Holiness Movement (Urbana, Illinois and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), xii, 69; Deborah Vansau McCauley, Appalachian Mountain Religion: A History (Urbana, Illinois and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1995), 257; Elmer T. Clark, The Small Sects in America (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1965), 85, 98; Cheryl J. Sanders, Saints in Exile: The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in African America Religion and Culture (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 49-52, 56; and Robert Mapes Anderson, Vision of the Disinherited: The Making of American Pentecostalism (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), 223-227. For an examination of how readily radical evangelicals embraced modern advertising techniques, radio, and drama, see Betty A. DeBerg, Ungodly Women: Gender and the First Wave of American Fundamentalism (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990); Douglas Carl Abrams, Selling the Old-Time Religion: American Fundamentalists and Mass Culture, 1920-1940 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001); Quintin J. Schultze, ed., American Evangelicals and the Mass Media: Perspectives on the Relationship between American Evangelicals and the Mass Media (Grand Rapids: Academie Books, 1990); Lillian Taiz, Hallelujah Lads and Lasses: Remaking the Salvation Army in America, 1880-1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 4-5, 74-75, 79-90; Wacker, "Searching for Eden with a Satellite Dish: Primitivism Pragmatism and the Pentecostal Character," in Religion and American Culture, 445-46; and Edith Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody's Sister (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993), 266-68.

14. Joe Creech argues that Azusa was only one of many historical points of origin for Pentecostalism. However, he acknowledges its symbolic and theological importance. Creech, "Visions of Glory: The Place of the Azusa Street Revival in Pentecostal History," Church History 65, no. 3 (1996): 406-408, 420. On the massive impact of the Azusa Street meeting, see Cecil M. Roebeck, Jr., "Pentecostal Origins from a Global Perspective," in Altogether in One Place: Theological Papers from the Brighton Conference on World Evangelism, ed. Harold D. Hunter and Peter D. Hocken (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 166-180. Robert Mapes Anderson estimates that pentecostals published as many as seventy-four different newspapers in the early years of the movement. Anderson, Vision of the Disinherited, 75.

15. Benedict Anderson describes the unifying character of newspapers, which, as an extreme variant of print-capitalism, "made it possible for rapidly growing numbers of people to think about themselves, and to relate themselves to others, in profoundly new ways." Accordingly, the holiness-pentecostal newspapers' role in unifying the discourse of pentecostals proved particularly effective. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London and New York: Verso, 1998), 36. Ibid., 32-35. For other examples of the press creating coherent religious discourse, see also Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 11 and Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven, Connecticut and London: Yale University Press, 1989), 73, 75, 76, 146.

16. The leading sects that constituted the radical holiness movement were the Apostolic Faith (Kansas), the Fire Baptized Holiness Church, the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee), the Pentecostal Holiness Church, and the Church of God in Christ.

17. Edward Ayers notes that new musical styles (jazz, the blues, and country music) entered the South at roughly the same time as Holiness-Pentecostalism did: "Those who played and those who preached incorporated new ideas and styles from outside the South into their own distinctly Southern vocabularies." Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South, 373.

18. Long before the advent of Pentecostalism, the doctrine of Holy Spirit baptism had become the trademark of the holiness movement. Holiness people often equated the baptism with a second work of grace called "entire sanctification." Those baptized with the Holy Ghost and sanctified would receive power to serve and could live lives free from sin. Pentecostals departed from this conventional view and made speaking in tongues the evidence of receiving Holy Ghost baptism. Pentecostals, according to Grant Wacker, also came to believe that a person who had been baptized in the Holy Spirit would manifest one or more of the nine spiritual gifts described in 1 Corinthians 12 and 14. Grant Wacker, "Searching for Eden with a Satellite Dish," 441.

19. A. J. Tomlinson, "Journal of Happenings: The Diary of A. J. Tomlinson, 1901-23," 25 September 1908.

20. For a typical post-War holiness philippic, see George Hughes, Days of Power in the Forest Temple: A Review of the Wonderful Work of God at Fourteen National Camp-Meetings from 1867 to 1872 (Boston, Massachusetts: John Bent and Company, 1873), 10-17. For more on the connection to Populism, see, Joseph Whitfield Creech, Jr., "Righteous Indignation: Religion and Populism in North Carolina, 1886-1906" (Ph.D. diss., South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame, 2000); Norman Kingsford Dann, "Concurrent Social Movements: A Study of the Interrelationships Between Populist Politics and Holiness Religion" (Ph.D. thesis, Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University, 1974); and Randall J. Stephens, "The Convergence of Populism, Religion, and the Holiness-Pentecostal Movements: A Review of the Historical Literature," Fides et Historia 32, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2000): 51-64.

21. Wacker indicates that in the last two decades of the nineteenth-century evangelicals across the ideological spectrum "exhibited a deep and enduring fascination with the work of God's Spirit." Wacker, "The Holy Spirit and the Spirit of the Age in American Protestantism, 1880-1910," Journal of American History 72, no. 1 (June 1985): 54. For a history of the holiness movement in America, see Melvin Easterday Dieter, The Holiness Revival of the Nineteenth Century (Layham, Maryland and London: Scarecrow Press Inc., 1996). On the southern extension of the revival, see Briane K. Turley, A Wheel Within a Wheel: Southern Methodism and the Georgia Holiness Association (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1999). Examples of these new sects include: the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, the Church of God (Anderson, Indiana), the Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene, and the Apostolic Holiness Union.

22. On healing, see Raymond J. Cunningham, "From Holiness to Healing: The Faith Cure in America, 1872-1892," Church History 43, no. 3 (September 1974): 499-513 and Jonathan Baer, "Redeemed Bodies: The Functions of Divine Healing in Incipient Pentecostalism,"

Church History 70, no. 4 (December 2001): 735-771. For an analysis of the transformation from holiness to pentecostal, see Dayton, The Theological Roots of Pentecostalism (Metuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1987). On the millennial expectations of holiness-pentecostal groups, see Timothy Weber, Living in the Shadow of the Second Coming: American Premillennialism, 1875-1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983).

23. "National Camp Meeting," Knoxville Daily Chronicle, 24 September 1872, p. 1; 25 September 1872, p. 1. Seven years later, southern Methodists in Texas were similarly apprehensive about the holiness movement. In there chief periodical writers lambasted holiness "cranks" as prideful fanatics and disturbers of denominational peace. They were, as one critic wrote, outside agitators from the North bent on driving congregants "mad" and causing women to become "boisterous and rough." "Sanctification - So Called," Texas Christian Advocate, 1 November 1897, p. 4; 29 November 1879, p. 2. These fears are not at all surprising. The post-bellum battles between the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South revealed intense lingering sectional hostilities. See Hunter Dickson Farish, The Circuit Rider Dismounts: A Social History of Southern Methodism, 1865-1900 (Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, 1938), 25-26, 78, 101, 107, 161. Daniel Stowell, Rebuilding Zion: The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863-1877 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 130-145.

24. Living Words, April 1903, p. 7. The Bridegroom's Messenger, October 1 1907, p. 2.

25. The Church of God paper, The Gospel Trumpet, boasted of sixty thousand subscriptions in 1908. To this the editor hoped to add another 140,000 by 1909. The Gospel Trumpet, 10 December 1908, p. 15. In 1896, J. M. Pike, editor of The Way of Faith, wrote that his publication carried a circulation of eight to ten thousand in South Carolina alone and reached nearly every state in the Union. "Advertisements," The Way of Faith, 5 August 1896, p. 4. W. A. Dodge's Georgia holiness paper, The Way of Life, ran at six thousand issues during the peak of its influence. Around 1890, one-year subscriptions for The Way of Life cost one dollar. J. WM. Garbutt, William Asbury Dodge: Southern Holiness Pioneer, ed. Kenneth O. Brown (Hazelton, Pennsylvania: Holiness Archives, 2001), 69. In 1900, the editor of The Firebrand reported a circulation of 10,000 issues, some for regular subscriptions, and others for sample copies. The Firebrand, November 1900, p. 1. Two holiness papers, The Way of Faith and The Pentecostal Herald focused almost exclusively on the movement's peculiar views concerning eschatology, healing, and entire sanctification. By the mid-1890's, the vast majority of southern holiness folk had adopted beliefs in healing and, more importantly, a pessimistic end-times theology known premillennialism. Holiness adherents cited a number of reasons for accepting premillennialism. Most felt rejected by mainline churches and came to see the world as fundamentally corrupt, even irredeemable. Southern premillennialists believed Christ would return before the millennium to take his loyal followers into heaven. Hence, they grew increasingly uninterested in social reform. If anything made the southern holiness movement unique it was the nearly unanimous adoption of these views. Every issue of The Way of Faith for 1896 included pieces on either the premillennial coming of Christ, healing, or both. Readers of Southern Methodist periodicals would have rarely if ever seen articles on these themes. For an excellent treatment of premillennialism among early pentecostals, see D. William Faupel, The Everlasting Gospel: The Significance of Eschatology in the Development of Pentecostal Thought (Sheffield, England: Shefffield Academic Press, 1996).

26. The Way of Life listed 157 books for purchase in an 1891 issue. These ranged in price from ten cents for Wesley's ever-popular Plain Account of Christian Perfection to three dollars for a two volume set of Frances R. Havergal's poetry. "Our Book List," The Way of Life, 24 June 1891, p. 4. An 1885 issue of The Christian Witness advertised 211 books and tracts for sale from a wide range of holiness affiliated authors and hymn writers. "Books and Tracts on Christian Holiness," The Christian Witness and Advocate of Bible Holiness, 5 November 1885, p. 7.

27. Live Coals of Fire, 27 October 1899, p. 4. Eva M. Watson, George D. Watson, Fearless for the Truth (Salem, Ohio: Schmul Publishing Company, 2001), 54.

28. "Denominational Loyalty," Southern Christian Advocate, 26 August 1886, p. 4.

29. Emma Christmas, "An Experience," The Way of Faith, 8 January 1896, p. 5, 25 November 1895, p. 4. The Way of Faith solicited this help with adds calling on readers to circulate holiness papers and magazines. For one dime agents' names would be added to the Holiness Exchange List, a document "sent to all publishers of holiness literature." These publishers would then mail sample copies to those on the list. The Way of Faith, 25 March 1896, p. 7.

30. W. C. Dunlap, Life of S. Miller Willis: The Fire Baptized Lay Evangelist (Atlanta, Georgia: Constitution Publishing Company, 1892), 140. I. E. Lowrey, "The Colored Ministers and Bishop Taylor's Steamer," The Christian Standard and Advocate of Bible Holiness, 8 March 1887, p. 2.

31. Southern holiness and pentecostal folks seldom identified with the shibboleths of sectionalism. In their papers they never championed the Lost Cause which the mainline press so often did. Historian Roger Glenn Robins finds radical holiness representative of a growing late nineteenth-century transregional culture. The connections holiness advocates made with other believers throughout the country—much like Populists, temperance enthusiasts, and women's rights activists—undercut regional and local affiliations. Moreover, holiness people came to think of themselves as part of a larger religious family that obliterated many sectional, class, and racial barriers. Roger Glenn Robins, "Plainfolk Modernist: The Radical Holiness World of A. J. Tomlinson" (Ph.D. diss., Durham, North Carolina: Duke University, 1999), 47, 48, 103-105. Robert Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), 47, 53. Holiness advocates often testified to being cleansed of all sectional prejudice. For examples of this phenomenon, see W. C. Dunlap, Life of S. Miller Willis, 26; "That They May Be One," Zion's Outlook, 7 February 1901, p. 8; and Timothy Smith, Called unto Holiness: The Story of the Nazarenes, the Formative Years (Kansas City, Missouri: Nazarene Publishing House, 1962), 178.

32. For example, A. J. Tomlinson, a founder of the Church of God (Cleveland), avidly read and corresponded with God's Revivalist, The Christian and Missionary Alliance, and Way of Faith. Robins, "Plainfolk Modernist," 264. J. H. King, a leading figure in the Fire Baptized Holiness movement and later in the Pentecostal Holiness Church, recalled being strongly influence by holiness papers like The Way of Life, The Vanguard (St. Louis, Missouri) and The Christian Witness. Joseph H. King, Yet Speaketh: Memoirs of the Late Bishop Joseph H. King (Franklin Springs, Georgia: Publishing House of the Pentecostal Holiness Church, 1949), 43, 81.

33. Percival A. Wesche, Henry Clay Morrison: Crusader Saint (Berne, Indiana: Herald Press, 1963), 62. I am indebted to William Kostlevy for providing me with this source. The Pentecostal Herald (Louisville, Kentucky), 9 February 1898, p. 1. Editor of The Revivalist, Martin Wells Knapp, changed the name to God's Revivalist in 1901. Lloyd Raymond Day, "A History of God's Bible School in Cincinnati, 1900-1949" (M.A. thesis, Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati, 1949), 22.

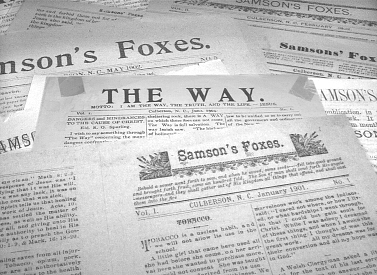

34. Wesche, Henry Clay Morrison, 52. Other holiness enthusiasts reasoned the same. Before W. A. Dodge began his The Way of Life, he had no experience publishing or editing a paper. Likewise, Texas holiness minister Denis Rogers edited and published his paper, True Holiness, though he "knew nothing about the printing business and had scarcely seen [the] inside of a printing office." Rogers made up for his deficiencies by taking courses in typesetting and editing at a printing office in McKinney, Texas. WM. Garbutt, William Asbury Dodge, 40. Dennis Rogers, Holiness Pioneering in the Southland (Hemet, California: n.p., 1944), 28. In January 1904, A. J. Tomlinson purchased a small treadle press for $125. With this easy-to-operate machine, Tomlinson began publishing The Way from his home in Culberson, North Carolina. Joel R. Trammell, "Publishing the Gospel," Church of God History and Heritage (Winter 1998): 2. Years before M. M. Pinson helped establish the Assemblies of God, he bought a press and type in New Orleans, Louisiana for approximately three hundred dollars. He intended to reach thousands with a planned holiness paper. However, an insolvent business partner wrecked the venture. M. M. Pinson, "Sketch of the Life and Ministry of Mack M. Pinson," 6 September 1949, Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center, Springfield, Missouri, p. 6.

35. Martin Wells Knapp, "The Revised Name," God's Revivalist (Cincinnati), 3 January 1901, p. 1. Similarly, in 1908 the pentecostal paper Latter Rain Evangel began publication, identifying the "Holy Sprit" as its exclusive editor. Wacker, Heaven Below, 139. On holiness adherent's use of pentecostal imagery, see Dayton, The Theological Roots of Pentecostalism, 174-75.

36. The Revivalist (Cincinnati), January, 1894, June 1894, January 1893. Lightning Bolts from Pentecostal Skies, or Devices of the Devil Unmasked was also the title of an influential book Knapp published in 1898. For the most incisive discussion of Knapp's role in the radical holiness movement, see William Kostlevy, "Nor Silver, Nor Gold: The Burning Bush Movement and the Communitarian Holiness Vision" (Ph.D. diss., South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame, 1996), 21-48. Synan, The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition, 41-43.

37. Turley, A Wheel Within a Wheel, 149-180, 65.

38. J. W. Buckalew, Incidents in the Life of J. W. Buckalew (n.p., n.d.), 55.

39. Charles Edwin Jones, "The Holiness Complaint with Late-Victorian Methodism," in Rethinking Methodist History: A Bicentennial Historical Consultation, eds. Russell E. Richey and Kenneth Rowe (Nashville: Kingswood Books, United Methodist Pub. House, 1985), 62, 63. Jones also alludes to the return to an evangelism of the past in Perfectionist Persuasion: The Holiness Movement and American Methodism, 1867-1936 (Metuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press Inc., 1974), 79-82. Timothy Smith traces these volatile years of "come-outism" in Called unto Holiness, 27-47. On the holiness reaction to Methodism and the restorationist thread, see Turley, A Wheel Within a Wheel, 151-167, 172-180. David Edwin Harrell Jr. discusses such religious revolts occurring in the South from 1885 forward in "The evolution of Plain-Folk Religion in the South,"in Varieties of Southern Religious Experience, 32-42. Similarly, James N. Gregory shows how holiness and pentecostal sects flourished among the Okies in the 1930s and 1940s. Hungry for the familiar world of plain-folk, revivalistic Christianity, Okies flocked to the new sects which catered to their sense of cultural loss. American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 191-221.

40. The Revivalist, June 1897, p. 6. W. B. Godbey, "Question Drawer," God's Revivalist, 31 January 1901, p. 12. A caveat: holiness and pentecostal groups' equality of fellowship seldom generated institutional equality. Donald G. Matthews, "'Christianizing the South'—Sketching a Synthesis," in New Directions in American Religious History, ed. Harry S. Stout and D. G. Hart (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 103.

There is Magic in Print, Part II

© 1998-2003 by The

Journal of Southern Religion. All rights reserved. ISSN 1094-5234

This article published 12/02