|

Taking Religion Seriously in the Deep South: An Interview with Wayne Flynt |

|

Conducted by Randall J. Stephens

|

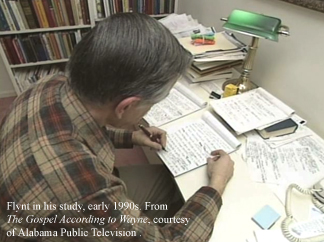

Wayne Flynt is the great contrarian of southern religious history. Whereas other scholars describe broad trends that mark the region—a white homogenous evangelicalism, parochialism, a regressive social outlook, etc—Flynt finds jack-leg socialist preachers, white liberal professors, and agrarians that certainly don't fit the mold. Flynt's work on the culture of the South's poor has influenced a whole generation of scholars. His Poor but Proud: Alabama's Poor Whites (1989) and Dixie's Forgotten People: The South's Poor Whites (1979; 2004) turned readers' attention to the countless southerners who, though marginalized by their "social betters," stood firm; strong in their faith, resisting class oppression. Flynt's long career and his work with a flurry of grad students over the years was celebrated in a 2006 festschrift: History and Hope in the Heart of Dixie: Scholarship, Activism, and Wayne Flynt in the Modern South. He was also the subject of an Alabama Public Television documentary, The Gospel According to Wayne Flynt (1993), from which we have streamed an excerpt below.

"I do so admire Wayne Flynt," said Harper Lee, author of the southern classic To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). "Here is a man with a gift for making long ago and the recent past come alive. He writes with an unclouded clarity, and makes writing history the work of an artist; I savor the delights of Alabama in the Twentieth Century." For insight on his life as a historian, a Baptist, public activist, and mentor, Randall Stephens spoke to Flynt in late October 2007 at the Southern Historical Association in Richmond.

Randall Stephens: I'd like to ask you about the early field of southern religious history. How did things look in the 1960s and 1970s, when Kenneth K. Bailey, Rufus B. Spain, and Sam Hill charted out their scholarly course?

Flynt: It's interesting that a lot of people still associate me with the early days of this field, which I wasn't a part of. I'm not the first generation; I'm the second generation really. I didn't have any particular interest in religious history early in my career. Though I had been a ministerial student as an undergraduate, I was reacting to segregation in the church, which is why I subsequently left the ministry.

Stephens: What first drew you into the field then? What did you make of Sam Hill's now-classic study Southern Churches in Crisis (1966).

Flynt: I read Sam's because I was interested in it, and I was certainly delighted with this sort of early glimmer of something other than an absolute uniformity in southern religious history. And the work of Bailey, and John Eighmy was inspirational. In their scholarship one already began to get the main trajectory of the story. But the studies of these historians provoked new questions for me. Though I agreed with much of what they had written, I was interested in the lives of ministers and laypeople, who by no means fit a uniform history of religion in the South. A hard look at the region revealed anything but uniformity. Yet religion departments in southern schools forty years ago were pretty homogenous. Most professors were orthodox, and so was I, and having gone through an undergraduate program at a Baptist university, where nobody believed you had to choose between creationism and everything else, I really felt the story had been badly distorted.

Stephens: Did you read Lillian Smith and Harper Lee in the 1960s?

Flynt: I did. Harper Lee had a major impact on me. Her book To Kill a Mocking Bird made me reconsider Alabama. Before I read that I had a negative impression of the state. I started grad school at Florida State in 1961 and the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed in 1963. I remember going home in 1961 and telling my wife that I didn't know where we'd end up teaching, but it would never be in Alabama. I'd never go back there.

Stephens: As you've written in a short piece—"A Pilgrim's Progress through Southern History," Autobiographical Reflections on Southern Religious History (2001)—you attended First Baptist Church in Tallahassee, Florida in these years.

Flynt: That's true. In 1964 that church had a vote on integration. The church chose to remain segregated.

Stephens: Did segregationists have a weaker theological argument than did integrationists? I wonder what you make of David Chappell's argument in A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (2004) about that matter.

Flynt: The segregationists' argument was almost wholly cultural, and not religious at all. Tallahassee's First Baptist Church made a political case, since it was the major church for the political establishment in the state's capital. A lot of really overt racism in that church was political. Older church members who were inactive showed up to cast ballots in the 1964 church vote on integration. They showed up that night and voted, and we didn't recognize many of them.

Stephens: Did the issue break down along generational lines?

Flynt: It was generational, overwhelmingly so. We had a very young pastor from the West, which meant he was theologically fairly conservative and socially quite liberal, as were Texas Baptists and Oklahoma Baptists.

Stephens: Did he attend seminary in Kentucky?

Flynt: No, he was from the Southwest, so he didn't go to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, in Louisville. Of course, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, in Fort Worth had a tradition of being the most liberal in terms of ethics. A whole generation of ethicists from Southwestern was quite liberal on the issue of race. That was partly because there were so few blacks in Texas. Yet theologically Southwestern was more conservative than Southern.

Stephens: The liberal/conservative lines can get rather blurred when we look at how American Christians have worshiped. I'm curious about your own theological or ecclesiastical views.

Flynt: High pulpits bother me. I don't like split chancels either. I like the pulpit in the middle and the emphasis on the word. I like the pulpit as low as it can be in terms of the congregation. I don't think there should be a great divide between the clergy and the congregation.

This partly reflects my populist political views. My early work at Florida State was in political history and labor history. My first two books were a biography of Senator Duncan Fletcher (1859-1936) and Governor Sidney Catts (1863-1936) of Florida. A lot of people see Catts, who was a Baptist preacher from Alabama, as the harbinger of my scholarly trajectory. That's not really true. Catts fascinated me solely because of his politics, and I found his religion to be a very interesting background for what he became, which was a southern demagogue, an anti-Catholic hypocrite. His daughters told me, for instance, that he drank alcoholic eggnog while campaigning against alcohol. He was involved with organized gambling in the 1920s. That was all behind the scenes. On the other hand, he was one of the most, if not the most, progressive governors Florida had in the early 20th century. He championed prison reform and education reform, and ran against the power brokers in the Democratic Party. Of course, he was elected not as a Democrat, because the Democrats stole the election from him. He was elected as a prohibitionist. He basically tried to create an independent third party that would be closely allied with Tom Watson and the old Populist anti-Catholic tradition. I found that all extremely intriguing.

At that same time I was working a lot on labor history. I wrote a paper on the 1908 transit strike in Pensacola. And I actually did research for a full-scale book on labor in Florida. One of the things I ran across was the fact that so many of these labor leaders were coming from Nazarene churches. They were also members of working-class Baptist churches. Labor in the South absorbed this extraordinarily powerful reform ethos of evangelical religion. Labor leaders in the West Virginia Coal Mine Strike of 1920, or the Birmingham Strike of 1919-1921 quoted the 25th chapter of Matthew, the Sermon on the Mount, and referred to the life of Christ. All those strikes were informed by the ethos of the Gospel. This was not Marxism. If they were socialists, they were Christian socialists, but their radicalism was a radicalism born of the church and the very literal teachings of Jesus. You could argue that they were fundamentalists—in terms of their believing that every word of the Bible was literally true—but when they quoted Jesus they picked passages that didn't make polite society feel good.

Stephens: Do you think religion has been integrated into the master narrative of southern history?

Flynt: It hasn't been integrated very well. Take, for example, C. Vann Woodward. There's no way Woodward, in the master research he did for his Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (1951), could have missed it. It must have been a blind spot. Perhaps he wasn't looking for it, or maybe he didn't want to find it. Given his experience with the Methodist Church in Arkansas, he was fleeing from it like almost all intellectuals were in the 1920s and 1930s. If a historian really feels like religion produces segregation, or that religion is a major bulwark for conservatism, or that it produces the rigid political hierarchies of the church, then it's easy not to see it.

In almost all the classes I taught I asked: "What role does religion play in the lives of the people who take it seriously?" What I like about the question is that it is an absolutely neutral question. It doesn't assume you are religious or irreligious. It just assumes you start off with a premise that's fundamental in any historian's work. If you bring a judgmental kind of attitude to your research, you do what every historian is told not to do.

Stephens: When you were doing your work in the 1970s, did you encounter historians who thought that religion was always a mask or a function of something else?

Fynt: Oh absolutely. And the thing I was always battling against my whole career was the sort of political correctness that was present in history departments then. When I went to Auburn, some colleague said, "We like you a lot, but we wish you wouldn't go to the Baptist church." They liked me, but it was always as if they liked me in spite of my faith.

Stephens: Your work often strikes a dissonant chord. To what extent did the progressive Parker Church, a Baptist church, influence the groups and individuals you write about?

Flynt: It was certainly the most influential congregation I was in. We moved around a lot so I was exposed to many churches, but that was the most influential one. When I was growing up in Aniston, Alabama, we had a World War II naval chaplain who had come from Texas. Pastor Locke Davis went to the South Pacific as a traditional conservative Baptist, and suddenly he was doing last rites for Catholics and ministering to Jews on ships that were hit by Kamikazes. World War II changed the faith of a whole generation. They had not been very progressive. They were quite close-minded, but in that setting they changed. Davis came back, he never felt comfortable in the SBC, and actually pastored a church out in Missouri that was aligned with the American Baptist Convention and the Southern Baptist Convention, and when he decided to leave that church he had two offers. One was from the American Baptist Church in Detroit and the other was Park Memorial. For a number of reasons he decided to come to Park Memorial instead of Detroit. I don't know, I did an oral history with him but I never asked him that question about his decision.

Stephens: Could you say something about the pacifism of Davis's predecessor in the Parker pulpit, Charlie Bell?

Flynt: He voted for Norman Mattoon Thomas, socialist and pacifist presidential candidate, twice. Bell formed a racial cooperative based on another southern model, Clarence Jordan's Koinonia farm near Americus, Georgia. Bell had blacks come to eat in the living room and dining room of his house. They entered through the front door rather than the back one. He was just scandalous, for that era, and the only reason he survived was because his father owned the largest bank in town, and because of the editor of the local newspaper, a very high-ranking member of the Democratic Party in the state.

Stephens: When I read your work about some of these fascinating figures I have wondered how unique they were.

Flynt: Oh this was very unique, and I'm not seeing that growing up, as a kid I'm not seeing that, I am seeing it as, "this is how Baptists are, this is how all Baptists are." I was seventeen and preaching already, but people were supportive of what I preached, and very supportive of me. Civil rights was not yet on the agenda.

Stephens: You have written that you became more and more aware of the race issue. Was it toward the late 1950's or maybe after the Montgomery bus boycott?

Flynt: I don't remember race being a big thing in the late 1950s. The Brown v. Board decision was irrelevant in Alabama in 1958. While I was in school, of course, the freedom rides occurred.

Stephens: Do you recall hearing about the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the news?

Flynt: Certainly. But the freedom rides loomed more large for me. I'm working on a memoir now and the first public position I took on anything was against a letter in the Anniston Star defending the Adams brothers who had attacked the freedom rider's bus in Anniston and burned it. They used a passage in the New Testament about Jesus scourging the moneychangers in the temple to justify violence. It just absolutely infuriated me. So I wrote a letter to the Anniston Star and asked what do you do with the Sermon on the Mount. The idea that Jesus engaged in violence at the temple is hardly an accurate reading of the text anyway. He didn't strike anybody, he didn't destroy anything, he upset the tables and he may have given them a tongue-lashing. But that was about as far as he went. Of course, I got a lot of angry reactions.

Stephens: How old were you when you wrote that?

Flynt: I was twenty. I couldn't even vote. I had been president of the student government association. I had been on the debate team. I don't know if I could have gone to college if I hadn't had a debate scholarship. In those years I was disgusted by the Democratic Party, which was represented then by Governor John Patterson and George Wallace. So I saw Republicans as the liberal alternative to the racism.

Stephens: Was Lyndon Johnson the first Democrat you identified with?

Flynt: He was the first Democrat I supported. In 1964 I had to form a group at Florida State called "Republicans for Lyndon Johnson" and I actually did door-to-door campaigning for the Democratic ticket. By 1968 I switched parties. The Barry Goldwater period in '64 had convinced me that the white South was going to switch to the GOP, which was what happened. By then I was a pretty liberal Democrat. In fact, when I went back to Samford to teach in '65 one of the first things I did was form a tutoring program in Rosedale, a black community. Rosedale High School had no equipment, and it was in a kind of ghetto. The first black student to enroll at Samford was a graduate of the tutoring program that I started, which was sponsored by the Young Democrats and the Baptist Student Union. I was proud of those groups. We were able to bring those two groups together, and there was a lot of overlapping membership too. I also started a drive in Rosedale to register black voters in '65. A lot of my students went door to door getting people to register.

Stephens: Was there tension over that?

Flynt: Oh yes

Stephens: From church people?

Flynt: Not from church people so much. I was at Baptist church at the time and there were a lot of people who didn't like integration and didn't like people doing stuff like that, but they didn't really know what I was up to. I had a young family and was a new member of the church. A telephone call from the pastor in Tallahassee told this Baptist church that I had been trained in Cuba and smuggled across the Mexican border to integrate the First Baptist Church in Tallahassee, which the pastor thought was the most amusing thing he ever heard. With my limited Spanish I would have starved to death, and never would have made it back.

| |

|

At any rate, there was that kind of stuff, but the people up there didn't really know much of what was going on. After the Voting Rights Act, I took some African American to vote who didn't know how to read or write. When she asked me to help her in the voting booth there was a furious reaction from the registrar. He said "you can't do that." I said, "we need to get someone from the Justice Department to instruct you on what I can and cannot do because you obviously haven't read the Voting Rights Act." I do have a temper. I lost it that day, and told them they might very well haul me off to jail but I was going into that voting booth and I was going to help her vote whether they liked it or not. There was that kind of confrontation, and the very first black student who came to our church was one of my students, he was a pharmacy student from Nigeria. That made the first round of integration more acceptable.

Stephens: That was the same with the Nazarenes.

Flynt: It was the same at Mercer University, too. Their first black student was a Nigerian.

Stephens: The first black faces you see in evangelical college yearbooks in the 1960's tend to have African names beside them.

Flynt: It made it convenient, because these individuals were the products of our missionary efforts. The Nazarene Church, pentecostal churches, the Church of Christ, and the Independent Baptists had a strong missionary outreach. The Presbyterians, the Episcopalians, the Methodists had already gotten out of missions. They were too embarrassed by it. So they were the ones who were reaping the harvest of the missionary movement.

Stephens: Could you describe how some within your boyhood community of Anniston, Alabama eventually grappled with issues of race and social justice?

Flynt: Race relations were probably the last bridge to be crossed on the journey for most. Charlie Bell, at Parker Baptist Church, was quite liberal on race. He and a handful of others brought a resolution in the 1930s to the New Orleans Baptist Convention. Bell did it to counter the Christian Life Commission, as it was later called, which brought up a resolution about alcohol. Charlie was furious. He got to his feet and said "Here we are with a quarter of our population without jobs and poverty and starvation in our land, and here you are passing resolutions about alcohol as if that's the most important issue." What they did is they started talking about race. W. O. Carver, one of the most liberal members of the faculty at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, was one of Charlie Bell's teachers. So, all of a sudden you have this movement that begins to at least run around the issue of race, and they had already taken a position on an awful lot of contemporary social problems: poverty notably, share cropping, tenant farming. Sure, there were a lot of Baptists who did not get interested in anything because they were too busy saving souls.

Stephens: That reminds me of why Sam Hill's work on the South resonated with me. Growing up in the Nazarene Church, as I did, it seemed the great commission crowded out all other concerns. Yet that was an evangelical development that was certainly not limited to the South.

Flynt: And it seems to me that this is the staying power of Sam's book. If you're looking for the core, the guts of what southern religion is all about, it is conversion. I never argued the other side of that. I conceded that from the beginning. John Boles always said that this is boiled down to the issue between splitters and lumpers.

Stephens: It is interesting, then, that you have found so many figures in southern history, many not attached to institutions, renegade preachers and the like, who do not figure into the work of other historians. I found some of these people in my research as I mined denominational papers for pentecostal voices. How have you found some of these fascinating individuals?

Flynt: Backwards. What basically took me into reconstructing history backwards was my first book, Duncan Upshaw Fletcher: Dixie's Reluctant Progressive (1971), based on my doctoral dissertation. When Fletcher died—after he had been one of the most influential men in the U.S. Senate during the first few decades of the 20th century—his secretary, the interim Senator chosen to take his place, burned all of Fletcher's papers. He had no space to store them and nobody wanted them in those days. So when I was writing my dissertation, I had to go to somebody else's papers to find his letters. I went to Carter Glass's papers, I went to Woodrow Wilson's papers, and I went to Roosevelt's library. And I reconstructed background.

By the same token, if you can't find anything about Populist-supporting preachers in denominational newspapers, you must go to the Populist papers. Populist newspaper editors invariably took such pride in ministers who supported Populism. Historians who have written about Populism have pointed out that populist rhetoric is straight out of the gospel. These individuals upheld the idea that there is a world of justice out there and the world is to be changed by Christians who apply the gospel to all sorts of unjust situations. The temperance movement was clearly there because the Democratic Party was a wet party. The Populists were running dry.

|

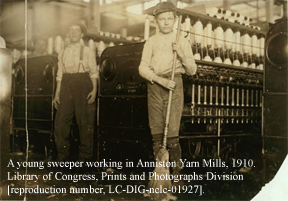

But the most important thing was the vocation of those who supported Populism. They were coal miners in Alabama. Alabama is the most industrial southern state. It is the state with the largest number of union members outside of Kentucky. In many ways it's more like Pennsylvania than it is like Mississippi, and therefore you get people who are being forged by the same kind of things that were happening in Pittsburgh.

Stephens: I didn't know that about Alabama.

Flynt: Aniston was the soil pipes center of the world, which means they made sewer pipes for Cairo, Egypt. These Aniston pipes were used all over the world. They also had railroad shops, which made railroad cars. As a result Aniston was basically divided in two. West Aniston was working class through and through, while East Anniston contained those who had crossed over, the wealthier.

Stephens: I recall you describing East Aniston as having a kind of country club atmosphere.

Flynt: That's right. My dad was very much from West Aniston. He moved to the East side when he got the money. He aspired to be a part of that world. The first place we lived was one fence removed from the black section of Aniston, right on the boundary of East and West Aniston. When we came back, Dad was a manager, he managed the branch even though he never went to high school, and he had made enough money and was successful enough as a businessman. There were two sides up on the mountain. One was very rich, with wonderful houses, and the other, the side we lived on, had very simple abodes. But they were the kind of homes my Dad could afford.

Stephens: Do you think this is a kind of a metaphor for your work? You seem to be in between in a way; you see things from these two different sides.

Flynt: Absolutely. That is absolutely true Randall. A lot of people assume I wrote the sort of history I wrote because I was so fiercely determined to have the world I came from represented. Actually the truth is that until I began to do research on poor whites in the South I had no idea of the poverty of my parents. They had very carefully shielded me from it, the same way first-generation immigrants shield their children from the Old Country. They don't want their children to be Old Country. They don't want them to talk like that, they're perfectly happy for them to be totally different. Which is why second-generation people usually are running from that.

When I was interviewing my dad I was teaching a world history class, and I started interviewing him because I remembered his stories when I was in my thirties. When I began to talk to him—he was an incredible storyteller—the pressure of modernity and my mother always saying: "Homer get to the point . . . Homer they don't want to hear that story . . . Homer they've heard that story 15 times," made him truncate his stories, so it was never as rich as when I had first heard it. Both my mother and dad had been extremely poor, but by the time I had been born they were moving into the lower middle class and the middle class. They never talked about that world they had once been a part of. Dad told stories, rural stories about farming, but only when I began asking probing questions about my grandfather especially, a sharecropper. Then my dad began filling those stories in. So, in a sense, I was almost like a second-generation immigrant kid who decided he wanted to know where he came from.