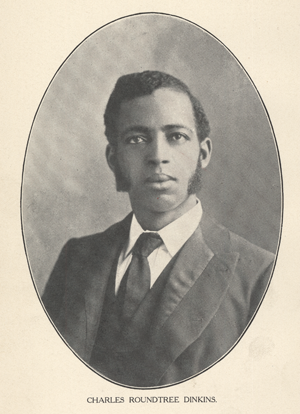

A Black Minister at the Nadir: The Poetry of Charles Roundtree Dinkins

Randal L. Hall

Managing Editor, Journal of Southern History

Associate Adjunct Professor

Rice University

In 1904 Charles Roundtree Dinkins published Lyrics of Love, a collection of more than one hundred of his religious and secular poems.(1) The Columbia, South Carolina resident was a minister and an African American community leader; and in his poetry lies all the dilemmas of a man in a deeply racist place and time. But he nonetheless claimed space for African Americans—he used his poetry to call on white people to recognize the two races' shared stake in southern soil and history. When such appeals fell on deaf ears, as increasingly they did at the time, Dinkins turned his readers' eyes heavenward as the only solution.

|

Lyrics of Love attracted some attention following its release. A 1906 advertisement from the publisher, the State Company in Columbia, quoted an approving review from the Boston Transcript, which labeled the book "the work of a colored poet who shows considerable versatility, poetic insight and skill in rhyming." However, the same advertisement by the white publishers also quoted the Charleston News and Courier's review, which was based on stereotypes: "These verses by a colored clergyman of Columbia have all the melody and fervor of the emotional race to which the author belongs."(2) The Independent magazine downplayed the book, judging that "the larger part of the volume is of religious verse of a crude order."(3)

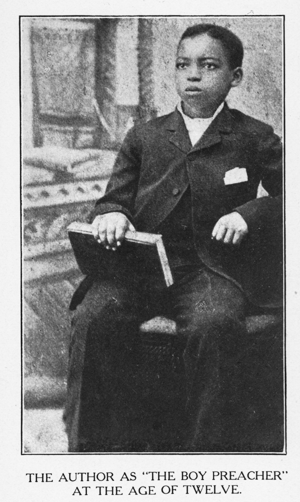

In 1924 Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson, two white academicians in North Carolina, released An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes. Preceded only shortly by two similar collections—one of them a famous anthology by the black writer and activist James Weldon Johnson—White and Jackson's work had something that neither of their competitors did: three poems by Charles Roundtree Dinkins. Jackson, a historian responsible for writing short biographies of each poet, had little to say about Dinkins: "Of the subject of this sketch we have been able to learn only that he is a minister of the A. M. E. Zion Church and that he published a little volume of poems, Lyrics of Love, Sacred and Secular, at Columbia, South Carolina, in 1904, from which these selections are taken. His last ascertainable address was New Bern, North Carolina."(4)

Even since then, though, little new light has been shed on Dinkins's life and poetry. In 1997 literary historian Keneth Kinnamon surveyed anthologies of African American literature. He dismissed White and Jackson's work as a condescending and biased work that favored dialect poems. But Kinnamon discerned one redeeming trait in their book: "Still, where else will one find . . . Charles R. Dinkins?"(5)

Indeed, some of Dinkins's work deserves to be found and read. The commonplace religious poems occupy more than half of his book, and his secular poems cover a variety of topics, including humorous takes on married life. But the handful of poems that deal with the South, race relations, racism, and the region's history offer a vivid and still valuable peek inside the conflicted mind of a man caught in the hardening world of early-twentieth-century Jim Crow. In these verses, one finds Dinkins dissecting white hypocrisy yet professing Christian love for white people. He proclaims his adoration of the South, even as he points out the brutal lynching of blacks. He joyously celebrates black humanity, manhood, and freedom, but he laments Wade Hampton's death and appreciatively imagines the farm-bound dreams of Booker T. Washington.

Dinkins's religious poems and his poems about love are typical in their themes and conservative structure; many of his better-known peers among black writers sounded these same notes. Like other poets he emphasized self-discipline and sentiment, criticized racism, and hoped to be identified as both a black man and an American with political and social rights. But in the poems reprinted here, he was at the forefront of his generation in certain ways. Historian Dickson D. Bruce Jr. has written that leading black writers had considerable "difficulty in formulating a consistent ideological response to racism in the closing decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth. If it had become clear to many people that older assimilationist strategies had little chance of success, there was also a nagging sense of the negative base on which separationist ideas and strategies rested." Dinkins fits the profile of an imaginative writer in a transitional time, a man who found no consistent, workable outlook for the world around him. Other black writers soon moved beyond Dinkins by creating independent, even nationalist, artistic forms aimed solely at black audiences, but Dinkins in 1905 had already shown pessimism about blacks' ability to make progress against the hindering hand of whites. At moments, his exploration of despair and violence put him in the company of cutting-edge black writers, men like Paul Laurence Dunbar and Sutton Griggs.(6) Like them, he had no clear solution to the puzzle of how to live in a white-dominated society, but he did capture the quandary with eloquence.

At the core of that quandary lay white southerners' refusal to treat blacks justly. Dinkins laid out his hopes, and their tenuous status, in "We Are Black, but We Are Men." "Justice' mansion has no cellar," he wrote: "We must share the rights of others, / Dwelling here as kin with kin." He put blacks at the heart of both region and country. "We're a part of this great nation," the poem proclaims; and in the next verse, Dinkins zooms in on the South: "South, the land we love so dearly, / Wilt thou plunge us in despair?"

Dinkins fights such despair in poem after poem. "An Appeal from the Stake," with which Dinkins opened the secular portion of the book, takes the reader to the heart of despair. The narrator, being torched by a lynch mob, reaches out prophetically toward whites: "Am I not still your friend, / Though flayed and tortured here?" He appeals to whites' conscience—"Why make a hell for mine, / And heaven for yourselves"—as well as to their self-interested devotion to their home region. "Why stain your blesséd South"? he asks. Yet the narrator, like thousands of his fellow southerners, looks in vain to escape the "rabble's savage cry."

In "Gen. Wade Hampton," Dinkins brings his readers—many of them likely residents of Columbia, where the book was published—to their own locale. Hampton is termed "Greatest of Carolina's brothers, / Bravest of thy natal sod." The general's grave is "Shaded by an oak adoring / 'Neath Columbia's sunny skies." In paying tribute to Hampton, Dinkins echoes nostalgic white southerners, who recalled the Civil War longingly as the Lost Cause, but he does so strategically. He stakes a biracial claim to Hampton that underscores Dinkins's views of South Carolina and the southern past as places shared by freedpeople and former slaveholders. "Those whom you once held as chattels / Still recall thy name with praise," Dinkins writes. But he then lands his message: they "Wept to see you die, but saying / 'Father, bless both black and white.'" He hinted that the present generation of white people should likewise reach out across racial lines.

|

To readers in Columbia, the implication was undoubtedly clear, for Dinkins commingled a pragmatic tone and a piercing critique. During the 1890s and after the turn of the century, South Carolina's capital city had joined communities throughout the South in restricting further the already limited room for black progress and for white and black interaction. In surveying Columbia's history, scholar John Hammond Moore notes, "The years from 1890 to 1905 were unusually difficult" for black residents. New laws segregated railroads and streetcars and limited blacks' political involvement. The African American fire brigades and militia units were disbanded, and blacks became less welcome at the state fair. Lack of resources stunted black efforts to provide adequate health care and education for themselves.(7)

In 1903 Dinkins even helped lead a boycott of newly segregated streetcars in Columbia, a crusade that ultimately failed. Whites controlled the streetcar lines as surely as they had funded much of the construction of Dinkins's church. The Columbia State quoted him as declaring that the ordinance was an unnecessary affront: "Everything was going along pleasantly and preachers here have always avoided discussion of racial issues, preferring to try to inspire their congregations with faith in their own race and to encourage them to trust and to depend upon the southern white people."(8) Dinkins wrote his poems of protest while surrounded by an ever-tightening net of white supremacy, and in the poetry one finds considerably more ambivalence about white intentions than his public statements in 1903 foreshadowed. We can only speculate whether the failure of his political protests drove the tone of some of his poems, which were released the following year.

Certainly Dinkins's poetic tribute to Columbia State editor Narcisco Gener Gonzales tapped into local political tensions. Gonzales, cofounder of the paper, used its pages to oppose "Pitchfork" Benjamin Tillman's populist movement and to provocatively push the state's leaders to end race-baiting and lynching. Jim Tillman, a state official and the nephew of demagogue Ben Tillman, mortally wounded Gonzales with a Luger pistol in January 1903 on Columbia's Main Street, near the state capitol. To Dinkins, Gonzales "fell a wounded hero."

Though Dinkins lived in the city of Columbia, the southern countryside provides the backdrop for much of his poetry. Black southerners lived overwhelmingly in rural settings, and rural blacks faced deepening problems just as their urban brethren did. Dinkins effectively uses the vocabulary of the farm and landscape to give the poems richness and depth. "The Prophet of the Plow (Washington)" employs the farmscape most effectively as Dinkins portrays a dream of a young Booker T. Washington. "The South—the vast and wondrous whole / Appears before his gaze," Dinkins writes. In Washington's imagination, thrifty black farmers find, with education, "A lump of waiting gold" within "every foot of earth." "Tuskegee like a molehill starts / Then like a mountain stands," and soon "bright mansions" replace cabins. Dinkins here seemingly accepts Washington's vision; however, he places it at a distance by using the dream as a framing device, and the poet then undercuts Washingtonian optimism in other poems. Salvation would not come easily from southern dust, for whites controlled the countryside as well as the city. The narrator of "An Appeal from the Stake" succinctly explains racial hatred with a rural reference: "Why love your dogs and mules / Much better than your blacks?"

Dinkins, like Booker T. Washington, clearly hoped that the paternalism of white men in Hampton's tradition could provide breathing space for blacks in spite of the lynch-crazed "rabble." In "Let Him Alone," the poet similarly asks whites for tolerance, this time using humorous verses to gently remind them that the Negro "has some rights as well as you." This poem places blacks in both rural and urban locations—including "school," "the street," "your field," "your melon patch," and "your hotel"—and urges whites to stop magnifying blacks' faults and responding with oppression. So what if a black man steals a chicken: "Hens are fussy anyhow, / Let him alone." Dinkins looked to leading white people to moderate the wave of violence against blacks in the city and on the farm alike, but as his flame-touched narrator in "An Appeal from the Stake" again makes clear, Dinkins could not sustain Washington's earthly optimism.

Even the angriest "secular" poems point to a transcendent place. As in the tribute to the dead Hampton, mortality is a recurrent theme. For instance, in "No Longer a Slave," Dinkins shouts, "I'm happy, O Heaven! / Since now I am free: / Though nothing but a board / Shall point out my grave, / Still write on the head-piece, / 'No longer a slave.'" Despite Dinkins's assertions of earthly manhood and his (and Washington's) blueprint for material progress, the poem's movement toward heaven is a natural step. Caught in the depths between the savage hoi polloi and the unresponsiveness of so-called better whites, Dinkins could look nowhere—Tuskegee notwithstanding—but toward heaven for relief. The narrator in "An Appeal from the Stake" best captures that hope: "But God is also just, / Alike to weak and wise; / And from my smouldering dust / Shall your damnation rise!"

Like other black writers, Dinkins vividly diagnosed the problems of early Jim Crow America. Residing in the heart of a segregated society while explaining its rotten underbelly, he desperately tried to keep hold of both religion and poetry to pull him away from the depths of despair: "Yet in spite of Death the Raider, / And in spite of hellish strife; / We must rise from this low nadir / To the zenith of this life." How to get there—how to find justice without divine intervention—was the unanswerable question in 1904.

An Appeal from the Stake

Are pagan vices thin

Ye saintly Southern elves?

Why make a hell for mine,

And heaven for yourselves?

Why wake a nation's ire

To chase a fleeing mouse?

Why set the world on fire

To burn a humble louse?

With blood of lowly pride,

Why stain your blesséd South;

And take the Negro's hide

To wipe your holy mouth—

To justify your rules,

Whose anger never slacks;

Why love your dogs and mules

Much better than your blacks?

Your friend you view with scorns,

And bind with iron thread

His feet, that crush your thorns—

His hands that make your bread.

Why burn, revile and curse

The man who would not harm—

Who rocked your cradle first,

Who nursed you on his arm?

Was I not faithful still

When brother sought your life?

Why blame me for the ill—

The issues of your strife?

Why rage, my heart to rend,

And bid your love forbear?

Am I not still your friend,

Though flayed and tortured here?

I'll suffer—though 'tis hard—

The fury of your ire:

My blood shall cry to God

Against you from the fire.

Excuse will not avail,

For Justice will pursue;

"Who by the sword prevail

Shall by it perish, too."

Where is that spark divine,

Which often did console—

Did on my pathway shine—

Around my heathen soul;

That sacred spark of love,

Which shone so bright of yore?

Does it such friendship prove?

Is this the fruit it bore?

That love which breathed within

A confidence divine—

Which made me fear to sin—

Which joined my heart to thine;

Which bound me fast and strong

To my old master's feet;

Which made me feel, so long,

That chattel life was sweet.

Shall love at last subdue—

This Ethiop's heart refine;

And leave it still for you

To prove it less divine;

Who saw its shining first,

And found its dear embrace;

Who saw its glory burst

On all in pardoning grace?

And why debase the Good,

With Evil to be bound;

And spill thy brother's blood

With piety profound?

Will ye your honor stain,

Ye best and wisest known,

Bid vile Anarchy reign

With Justice on the throne?

Why spread the sacred Book

Before my dimmer eyes;

And then, with pious look,

Direct me to that prize—

By meek obedience won,

The pure in heart's reward;

Then draw your torch and gun

Against the heirs of God?

Ye tell me, "God is love"—

That I should this embrace;

Then, why so different prove,

Ye children of His grace?

That I should like Him be,

Forgiving, good and kind;

Why shout with joy to see

Thy friend in flames confined?

But God is also just,

Alike to weak and wise;

And from my smouldering dust

Shall your damnation rise!

You should remember now,

The lesson of those years

When Justice made you bow

In sorrow, grief and tears.

Though hopeless of your grace

While still my flesh consume,

I'll love the ruddy race

In spite of all that come:

In spite of gun or sword,

Or fagot's cruel flame;

Like Thee, my gracious Lord,

I love them just the same!

I love ye not for aught

That your strong hands have done—

Nor what your skill has wrought,

Nor for your triumphs won;

Not to appease your laws,

Nor Color's creed approve;

I love ye just because

My Father God is love!

In spite of stifling heat,

Or rabble's savage cry;

Still, still I now repeat,

I love you though I die!

And thus my soul would heave

Its dying breath for you,

And cry, "O Lord, forgive!

They know not what they do!"

Let Him Alone

"What must we with the Negro do?"

Let him alone;

He has some rights as well as you,

Let him alone:

When you seen go to vote,

With his head set like a goat,

Don't be pulling at his coat;

Let him alone.

When he's on his way to school,

Let him alone;

He is not the only fool,

Let him alone:

If he wears a beaver hat,

Why, don't bother him for that;

He's as happy as a cat;

Let him alone.

When you find him in your field,

Let him alone;

He can eat all he will steal,

Let him alone;

If he's in your melon patch,

And it's time for them to hatch;

Don't be sneaking round to catch,

Let him alone.

When you meet him on the street,

Let him alone;

He will work enough to eat,

Let him alone;

If he comes to your hotel,

He is guided by the smell,

Please don't run him down to ——ll,

Let him alone.

If he's in your chicken house,

Let him alone;

It might only be a mouse,

Let him alone:

Though your chickens start a row,

And are cackling "wow-o-wow!"

Hens are fussy anyhow,

Let him alone.

When he's studying politics,

Let him alone;

He is learning your old tricks,

Let him alone;

Though he cannot read his name,

Heaven knows he's not to blame;

He's a citizen just the same;

Let him alone.

We Are Black, but We Are Men

What's the boasted creed of color?

'Tis no standard for a race;

Justice' mansion has no cellar,

All must fill an even place.

We must share the rights of others,

Dwelling here as kin with kin;

We are black, but we are brothers;

We are black, but we are men.

Heaven smiles on all the dwellers

Of creation's varied breeds;

Virtue beameth not in colors,

But in kind and noble deeds.

Though in humble contemplation,

Driven here from den to den;

We're a part of this great nation;

We are black, but we are men.

South, the land we love so dearly,

Wilt thou plunge us in despair?

Wilt thou hate a brother merely

For the texture of his hair?

Boast yourselves as our superiors,

We allow your claim, but then,

We are black, but not inferiors;

We are black, but we are men.

When our God His image gave thee,

We received a mortal's due;

And when Jesus died to save thee,

Died to save the Negro too.

Stabbed by death, by sorrows driven,

Through one gate we enter when

Passing into hell or heaven;

We are black, but we are men.

Hundreds crowding every college,

What will ye to them impute?

Climbing up the tree of knowledge,

Reaching for the golden fruit.

To this creed the world converting,

There's no virtue in the skin;

Daily proving, still asserting,

We are black, but we are men.

Yet in spite of Death the Raider,

And in spite of hellish strife;

We must rise from this low nadir

To the zenith of this life.

Rising though they mob and seize us,

Hound and chase o'er moor and fen;

Rising by Thy grace, O Jesus!

We are black, but we are men.

Heaven hath your deeds recorded,

Vengeance is Jehovah's own!

And though late, you'll be rewarded,

You must reap what you have sown!

Trusting, Father, to Thy goodness,

We shall in the conflict win;

Yet, forgive our brethren's rudeness;

Let us live like loving men.

To the Sacred Memory of N. G. Gonzales

Embalmed in South Carolina's love,

He sleeps;

With lion strength and heart of dove,

He sleeps;

While o'er the tomb our heads we bow,

Love's final tribute to bestow;

Beneath a mound of flowers now

He sleeps.

With folded arms across the breast,

He sleeps;

Reposed in that eternal rest,

He sleeps;

Far from the loud, keen clash of strife,

Far from the love of friends and wife,

Far from the busy paths of life,

He sleeps.

'Tis but the wounded, mortal span

That sleeps.

'Tis not the higher, nobler man

That sleeps.

His soul, illustrious and sublime,

Soars high above the peaks of Time;

To that diviner, happier clime

He leaps!

Afterwards

There fell a man to virtue born—

To love a lord—to truth a king—

To law a priest, whose fate we mourn;

Beneath anarchy's venomed sting.

The fight for honor long had past,

And he, the victor in the strife,

Was smitten by the Luger's blast,

But triumphed more in death than life.

Beneath the dome where Hampton's voice

Still hums his last immortal lay,

Where once Calhoun (the people's choice)

With thunder rivaled thundering Clay;

A moving arsenal of death

Impaled its honored shrine in shame;

And with the fury of its breath,

Extinguished life's supernal flame!

He fell a wounded hero, low,

Yet thoughtless of his fate so nigh;

He threw his hands upon his brow

And looked into eternity.

Far viewed, the fields of Eden stood,

Inviting palm and waiting kin;

E'en on the margin of the flood,

He felt no consciousness of sin.

A stunning shock, a thrill of dread,

Aroused a trembling people's fears;

The messenger declared him dead,

And South Carolina bowed in tears.

A wounded State with Justice fled,

An orphan law with Mercy gone,

Bowed with an aching heart and head,

While bold anarchy trampled on!

Ah! weep with me, ye Muses here,

Lo! widowed love unpitied stands,

With face all torn by grief severe,

With broken heart and helpless hands—

Where lies a head with honor crowned—

Where finds the valiant heart repose—

Where sleeps a dear one 'neath the mound—

Where fades the violet and the rose!

Let marble shaft his ashes span,

And tell the listening ears of Time

The worth and virtues of the man—

The horrors of a sinner's crime.

Let fame a fadeless laurel give,

While his immortal annals tell

The life of honor he did live—

The cause for which Gonzales fell!

No Longer a Slave

No longer a slave, for

The ages are gone

Which bound us in shackles

Like monsters of stone;

Which hunted for mortals

Like beasts of the wood,

Despising the soul of

The helpless and good;

And herding and droving

The broods of the race

By the sting of the lash

And the frown of the face.

Thus hated and driven

From cradle to grave;

Now blest with their freedom,

No longer a slave.

No longer a slave, though

The dent of the chain,

And the wounds of the lash

Upon us remain;

Though the clouds of that day

So darkly depart,

Still hurling its thunders

Of wrath at the heart,

Still flashing its sabers

Of lightning again,

That terror may bind us

More fast than the chain;

But still unalarmed, in

The battle as brave,

We shout to the masters,

"No longer a slave!"

No longer a slave; for

The ransom was paid

By the life of the noble—

The blood of the dead—

By tears of the mother,

The woes of the wife—

The blood of the soldiers,

So fearless in strife,

Who, facing the cannon,

Inhaling its breath,

Did offer their lives on

The altars of death!

With groans of the dying,

And shouts of the brave,

How solemn the echo!

No longer a slave!

No longer a slave; now

In freedom to live,

In freedom to die and

To love and forgive;

In freedom to reign at

The family fold,

To shelter my own from

The storm and the cold.

Though only a cabin

My mansion may be,

I'm happy, O Heaven!

Since now I am free:

Though nothing but a board

Shall point out my grave,

Still write on the head-piece,

"No longer a slave."

No longer a slave; and

To heaven we sing

The praise of the Father,

The wonderful King,

Who gave to the Nation

A friend of the poor

Like Lincoln, who freed us;

That freedom we 'dore.

In word and in deed, and

In virtue and good,

We'll pay to this nation

The price of her blood;

A tribute of love we

Will pay to the brave,

Who fell, but exclaiming,

"No longer a slave!"

Gen. Wade Hampton

Veteran of a thousand battles,

Conqueror of unnumbered frays!

Those whom you once held as chattels

Still recall thy name with praise;

Those who knelt around you praying,

With their shackles harnessed tight,

Wept to see you die, but saying,

"Father, bless both black and white."

Though in calm repose you slumber,

All of life an afterdream;

Though you've gone to join that number

Far beyond the solemn stream;

Though you're harping with the singers

In that Home to which we tend;

Sweet! ah, sweet! the memory lingers

Of a master and a friend.

Right e'er found thee brave, but tender;

Wrong could not around thee grow;

Virtue knew thee as defender,

Vice regarded thee its foe.

Greatest of Carolina's brothers,

Bravest of thy natal sod;

Lo! thy life was spent for others,

For thy country and thy God.

Say, ye friends, let all repeat it

While receding ages move—

Fled from strife but not defeated,

Dead, but lives embalmed in love!

Speak, ye tongues, your chieftain's glory;

Rhyme his name, ye bards, and sing;

Tell to the unborn the story

Of the patriot, soldier, king!

Fame her sacred beams is pouring

Where the world's Wade Hampton lies,

Shaded by an oak adoring

'Neath Columbia's sunny skies.

Earth! the good increase thy numbers,

Clay! this mortal star enclose,

Tomb! in thee a conqueror slumbers;

Hampton resting in repose!

The Prophet of the Plow (Washington)

Recumbent on Hope's couch he lies,

Serenely calm and still;

To dreamland sweet his spirit flies

O'er ocean, vale and hill.

With eagle speed his pinioned soul

Encircles and surveys

The South—the vast and wondrous whole

Appears before his gaze.

At first the giant wild is seen,

With here and there a place

Where massive woods stand up between

The sparsely tilléd waste;

And there the thriftless toiler plods,

Nor gaining what is his;

He tramples on the golden clods,

And starves where plenty is.

Like hungry broods, his weeping race

Is crying loud for more,

While manna grows in every place,

E'en at the cabin door;

While taller heads than theirs demand

For rent, what crumbs they find;

And leave them empty purse and hand—

The worst, an empty mind.

There Woe and Want stand grim and tall—

More dangerous than the rope;

One slays a few, the other all—

A helpless people's hope!

Like herded brute they're driven still,

While stronger chains confine;

They toil and faint, the earth to till,

And eat the husk of swine.

Hoar Winter falls and finds them bare,

With nothing to inspire;

A host of shivering children there

Sit freezing at the fire.

Nor safely sheltered from the storm,

While biting winds invade;

Diseases at the doorway swarm

And death will not be stayed.

The vision takes a brighter turn

(And 'tis a smile of God);

His people gathering to learn

The mysteries of the clod.

He, their forerunner, stands to plead,

And pave their pathway now;

From far they come, with joy they heed

The Prophet of the Plow.

He sees in every foot of earth

A lump of waiting gold;

For every stroke, a drop of mirth;

And thus he cries, "Behold!

The ready fields their harvests shed;

Go forth, and plenty find;

Prosperity's rich store is spread

Before my people blind!"

The forest felled, bright mansions start,

The cabin to supplant,

While thrifty hand weds honest heart,

And Plenty buries Want.

He cries, there's bread for every mouth—

For each a portion just;

And the salvation of the South

Is wrapped up in the dust.

Back to the plow now each returns,

And to the waiting sheaf;

While Hope her sacred candle burns

And labor brings relief.

Vast fields on every side—how vast—

With proffered riches wait;

Go forth and reap, your sickles cast,

Nor grovel here too late.

Tuskegee like a molehill starts,

Then like a mountain stands;

The joy and pride of laboring hearts

Upreared by loving hands.

Proud sphinx and pyramid of mind

All former days excel;

Who enter in thy halls, though blind,

Shall not in darkness dwell.

Lo! the astonished nation views—

And marvels at the sight—

The prophet of contrasted hues,

Who leads his race to light.

And on his tiara they read

What ages could not find:

That curls upon the Negro's head

Can never chain his mind;

That blackness may be just as whole,

And just as pure and brave;

That color does not stain the soul,

Nor make the heart deprave.

A monument he rears above,

To all creation's view—

A monument of racial love,

Of faith and friendship, too.

Grief yields to song; made friends of foes,

While skill their hands employ;

And the sad tales of Negro woes

Are turned to shouts of joy.

Just then a rapid rustling broke

The sweet and pleasing spell;

An angel kissed him and he woke,

And made the vision real!