Randall Stephens: What drew you to the subjects of southern music and religion?

Steve Haisman: I think it was Southern music, and rural blues in particular, that was my soundtrack when I was a kid growing up in the 60’s. Of course, there was all the wonderful exciting pop and rock music—Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan and so on—and all the English bands who were playing Blues locally, in pubs and clubs—Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall—that took me back to the source, the original bluesmen from Mississippi. Robert Johnson, Son House and a lot of the other black “deep blues” musicians made a deep impression. It may have been simple romanticism, but I feel it was something more—there was something in the sound of those guys, as opposed to the musical idioms, that really attracted me. Their music had a content, it came from a deep place. I didn’t know it at the time, but I think I was more responsive to the existential elements than the music itself, imperious as it was.

David Eugene Edwards of Sixteen Horsepower and Steve Haisman David Eugene Edwards of Sixteen Horsepower and Steve Haisman |

|

|

Later, I came across Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. It was revolutionary. That collection deliberately mixed black and white artists, blues country, and gospel, without providing any information apart from the recording date, and a weird synopsis of the lyrics. No arbitrary classifications. Old-time white artists had an equally potent artistic voice. From there, I delved into people like Hank Williams and Dock Boggs and many other great white artists who laid the foundations for what we call Country music. Most of them learned the rudiments from some obscure black farm hand or itinerant and mixed this with their Anglo-Celtic oral traditions to make something new.

There was something else that intrigued me, more than the black or white issues. I heard Muddy Waters say that in order to play the blues, the deep blues—like he, John Lee Hooker, and a few others did—it helped if you were black. But more than anything else, for Waters, you “got to been to Church.” That made me think that musical genres were not solely tied to color. The content and sound of the music, and the experience of the performer, were all important. To me, Robert Johnson and Hank Williams both played the same kind of music—call it “Southern Gothic”—because their concerns are the same: existential dread and fear of eternal damnation, fighting for space with their longing for let’s say “worldly pleasures.” They share a real and tangible terror.

I think that Andrew, the director, and myself both wanted to make a film that traced the origins of that music—not in terms of sociology or musicology, but to the hard wooden benches of rural Southern churches. We wanted to ask the question: “Why does all this music and creativity come out of the South?”

Stephens: The film focuses on what appears to be a dying folk religious tradition in the region. Why did you turn your attention to that?

Haisman: What drew us to the music, both contemporary and archived, was that it all came from what you might call a real place. That authenticity seemed to contrast with our postmodernist world that has lost so many larger meanings. It may be partially true that southern roots music is dying, but it’s far from dead, just changing. Then again, it’s always been changing. (Some of the old “Christian” songs were grafted onto pre-Christian ideas—“The Coo-Coo Bird” is thoroughly pagan, an ancient mystery song that predates most Christian hymns.) In England, where I come from, there is effectively no religion. It’s just politics and class, and even those are losing their clear boundaries. So, of course, some people will want to find meaning of some kind in a world where there doesn’t seem to be any apart from materialism.

Stephens: At the outset of the film, the narrator Jim White comments that in order to make this trip he’ll “need the right car.” It seems like he’s incognito in that beat-up, 1970 Chevy. That made me wonder if, regardless of the Chevy, those you filmed were suspicious about the project. Did some question your intentions, and, if so, how did you handle that?

Haisman: Being English, and very conspicuously so, we had a kind of diplomatic immunity. We were totally shameless, and fearless, knocking on people’s doors, stopping them in the street, whatever. . . . Nearly everywhere we went people were very open and friendly—mainly because, I think, they sensed we were genuinely interested in what they had to say, and were non-judgmental. Also, we clearly weren’t from the ATF or the FBI! Most of the southerners we met had never seen an actual English person, and were as curious about us as we were about them. They were puzzled to find us wandering about in the backwoods and remote swamps. We had to give lectures in schools, and appear on local community television and radio. People offered us everything, from horrible drugs to salvation to “preacher suits,” but not many questioned our intentions—some questioned our sanity. . . . Right from the start, we reassured everybody that we weren’t interested in making fun of them for the amusement of sophisticated city folk—we were there to learn, and find the sources of the music and culture that we loved.

Stephens: White comments that rather than a “state of mind” the South is an “atmosphere.” Do you think that was evident in the filming of the documentary?

Haisman: I must admit I’m not entirely sure what he meant by that. If I had to guess, looking at it from the context of our discussions, I would say that he felt there was a spirit in the landscape itself, in the swamps and woods and mountains, that was as important in the creation of character, as history or sociology. It was part of our thesis that we didn’t want to look at the Civil War, didn’t want to look at the interaction of races, and instead wanted to look at the effects of the landscape—when Robert Johnson sings about going down to the crossroads, of course he’s singing about a state of mind. But we were also interested in that real place that may have prompted those feelings.

We read a book about Ferriday, home to Jerry Lee Lewis and others, which suggested maybe there were strong telluric currents that accounted for the profusion of eccentric, talented individuals who came from that tiny town. Maybe that’s the “atmosphere” that Jim was referring to? I never got round to asking him!

Was that atmosphere evident in the filming? Oh yes—there were plenty of places that had “atmosphere.” We got ourselves very spooked one evening, about to run out of gas in the exact woods where Pretty Polly—the innocent young girl from the eponymous murder ballad—was shown her shallow grave. I have to admit, Andrew almost shoved me in that grave, as I had overestimated the frequency of rural gas stations.

Maybe it was just us, but all the murky swamps and cypress groves seemed haunted. Then again, when we were in Knoxville, talking about another murder ballad, “Knoxville Girl,” we read a local paper that had an article about a girl who was murdered in an alarmingly similar way. Maybe time is cyclical, not linear, and there is a magic to a place?

Stephens: The film devotes some attention to Pentecostal church worship. Could you describe what it felt like to be filming inside these churches?

Haisman: We spent a long time researching, driving around in a mobile home in the dead of winter—we hate leaves and flowers, we are melancholy English people—and went into loads of churches. Walked in cold.

To be completely honest, we didn’t like some of them, especially those in which we didn’t feel welcome. At this time, we were driving around listening to the car radio, usually tuned into religious stations, and we found a lot of the broadcasts very depressing, and sometimes worrying. There was a huge amount of anti-gay sermons—urging boycotts of Disney, reminding us that nobody in the Bible committed sodomy and got away with it, and other equally blunt statements. Sometimes we went into Churches where there was a disturbing para-military feel, and the preachers were talking about the bombings of abortion clinics in a way that seemed to condone the actions. We didn’t film in these churches, because we found the environment too uncomfortable, and it wasn’t what we were looking for.

Instead, we found other churches, which were everything we thought a Church should be—tolerant, open, loving, embracing and a real asset to the small communities they served. We were welcomed into those, and people shared their most intimate moments of communion and worship with us, and were glad to explain their faith to strangers. There was a mutual respect. When we discussed our project, the preachers in such churches happily adapted their sermons to accommodate us: they referred to their music having its origins in King David, and how important the parables referring to “be ye hot, or cold, but not lukewarm” is to the Southern psyche. . . .

You have to understand that we come from a very liberal society. There were times when we found some things difficult to accept. But one element in particular struck us as vital to the folk religion in this region. That was the astounding oratory of the preachers. Even in the militaristic churches, the preachers really knew how to tell a story. One even used a live painting-in-progress to illustrate his lesson. The way the preachers told a

| |

Concrete lawn Jesus on the journey Concrete lawn Jesus on the journey |

|

story—using the glorious language of King James Bible melded with an often archaic Southern vernacular, adding a showmanship and sense of dramatic timing—was almost invariably spellbinding. One preacher admitted to us that he used the techniques of pulp fiction to get his stories across. Others used the language of circus barkers. All were very graphic and often gory. An observer might feel drenched in blood—and sometimes, literally drenched in spit as the preachers prowled through the congregation. One minister made vigorous stabbing motions as he described how the centurion wounded Jesus with his lance, and how the blood ran down the spear, down his arm, onto his tunic, onto his sandals, down into the desert sand where it stained it all red. . . . Yet the language and imagery kept us in the familiar modern world. It was astonishing!

We had a rule of thumb for picking out a church to enter. (There were just so many churches!) Whenever we saw a sign outside that read “Full Gospel,” and whenever there were more pickup trucks than family cars, we would go inside. The Full Gospel, as you probably know, indicates that they emphasize parts of the Bible others disregard, including Jesus' last words in the Gospel of Mark: “And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.” What puzzled us about this, and about many of the sermons in general, was how literal they were. We could understand the serpent as a metaphor, for being reborn, but to really go out into the woods and pick up a timber rattler!

Stephens: Were there things you left out of the film that seemed even too bizarre or unfavorable to reproduce?

Haisman: Yeah, quite a lot. I suppose the most important omission—the one that I regret most, probably—is the snake-handling churches. We had already decided we didn’t want to film them, as it was too extreme, and would be too sensationalist. But then, after we had finished filming, Andrew and myself had to take a hired car back, we had a little time to spare, so we called in on a snake-handling church in Virginia—or maybe West Virginia, Jolo—and that was the single most intense experience I’ve ever had, and the most extreme performance, if you want to call it, which I’ve witnessed. Out of all the churches, that was the one that really got through to me. In the other churches, both Andrew and myself—agnostics at best, children of rationalism—had both been surprisingly moved by the tangible presence of the Holy Ghost when people were speaking in tongues. This was something different. They were passing around timber rattlers, unmilked of poison, and drinking Drano or something like that. They weren’t just crazy hillbillies. No way! It made a lot of sense, and if I had been born in that dirt-poor community, I would be in one of those churches. But in the end I guess it worked out best that we didn’t shoot it.

Then again, there were other issues that we just walked past. The main one, which we heard about over and over, was the matter of guns. Everywhere we went, we heard what seemed a constant mantra—“ain’t nobody gonna take our guns from us!”This came up, at random, in bars, restaurants and so on. We met one man in particular, a restaurant owner in Louisiana, who had thirteen assault rifles and machine guns in an umbrella rack—all were loaded and ready to use. I’d never even seen one of these things up close before. And we met good Christian men, who felt the need to take loaded handguns with them when they went out hunting with bow and arrow “in case a junky from the city should come on to them, and they would just have a bow and arrow.” That would be out in the middle of nowhere!

Once again, we come from a society that strives to maintain a tradition of unarmed police, and no privately owned guns. But even though this situation in the South really puzzled us, it wasn’t at all relevant to our film.

The other issue that we didn’t feel we could address in this film was segregation. We were astonished to find it still prevailed in the rural areas. It didn’t seem like racism, but a matter of mutual agreement. I may be extremely naive here, but that’s how it appeared to us. We had already decided we wanted to focus on the marginalized rural white community, as their story had not really been told enough, and I’m still not sure if that was the right decision—but, for sure, it would make the film even more complicated had we included a debate about race.

Stephens: The sinner/saint motif in the film reminded me of the lives of pioneer rocker Jerry Lee Lewis and his cousin, the pentecostal televangelist Jimmy Swaggart. Lewis once proclaimed: “Either be hot or cold. If you are lukewarm, the Lord will spew you forth from His mouth.” And: “If I’m going to Hell, I’m going there playing the piano.” Those wild revellers you interviewed in a southern bar also speak the language of Evangelical Christianity. At one point a prisoner interviewed remarks that when he grew up as a pentecostal “there was no middle ground. You was either in church or you was into bars and parties. One way or another, there was no middle ground.” How did this strike you and the others who worked on this project?

Haisman: That was exactly what we were looking for. Because the stakes were very high, the music and writing were all the more powerful. As Flannery O’Connor wrote, “I am no vague believer.” We’re very vague, over in England. That’s why Jerry Lee Lewis could never have come from, say, Brighton, or some

cozy place over the water. It was our thesis that the art, the great, enduring folk art, arose from intense internal conflict. The church, and a strange Southern Jesus, was everywhere, even lurking at the bottom of all those wonderful morbid stories and old sinful blues records. Nothing is wishy-washy or compromised, every little thing matters, because a real and tough God is always watching you. No escape. So against that background you have to be pretty definite—and that’s what makes it so fascinating for us.

Stephens: How has the film been received in the U.K.? Do you feel that American and British audiences have responded to it in different ways?

Haisman: I think that a more interesting comparison is the way that supposedly sophisticated city people have seen the film—they may live in New York, Amsterdam, London, or Los Angeles. For those urbanites, the southern religious landscape in the film looked like a strange, exotic world. And that is something that is often as foreign to Americans as it is to Europeans. Of course, it’s more unfamiliar in some ways to Europeans—but for all our audiences, and we’ve seen quite a few at festivals and screenings, the thought in the background has always been the same: “this is the richest, most powerful nation on Earth, but its backyard is dirt-poor and medieval!”

Regardless of that response, we feel the film has done what we hoped—it asks questions, rather than provides answers. The main question being “Is what they have better than what we have?” Most Americans have not seen much of that world, judging from the responses at screenings.

Stephens: Some critics have written that the film caricatures the modern South with slackjaw, hillbilly stereotypes and Menckenesque observations. How would you respond to such statements?

Haisman: I would say those critics aren’t seeing the respect and affection with which we filmed all the contributors to the film. As far as we are concerned, nobody looks “slackjawed” in the film, and we didn’t

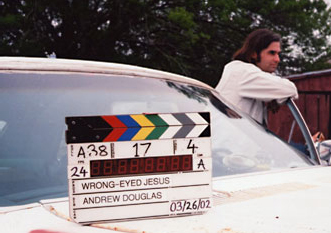

Jim White and Chevy Jim White and Chevy |

|

|

aim to make fun of anybody. We did meet plenty of stupid people—like you would in any country, especially our own—but we didn’t film any of them. Why should we have? As you can probably tell, it annoys me when people say our contributors are dumb yokels—that says a lot about the people complaining! I would never call any of them “hillbillies.”

As for stereotypes—well, of course people will be identifiable as “types,” from their clothes and accents and attitudes, but a stereotype is one-dimensional. I think all the people we filmed are a lot more than that. They are real characters with individual stories to tell, and once again if somebody wants to say they are stereotypes, I would say that’s their problem and maybe they should look beyond their surface prejudices.

Stephens: In an interview with the BBC, Andrew Douglas, the film’s director, commented: “The South of that film is very much a South of our own design. It’s a South defined by musicians and storytellers we liked, and by the Bible Belt.” Do you agree?

Haisman: Yes, I do. Following on from the last question, we didn’t set out to make a comprehensive, all-embracing documentary about “The South,” just that tiny little part of it that interested us, and fit into our admittedly obscure thesis. Hence there were a lot of people we left out—as Andrew put it, “All the golfers.” And, all the college professors, electronics engineers, surgeons, accountants, politicians . . . all that makes up the urban “New South,” and those who are part of the sanctioned “heritage industry.”

It simply wasn’t our intention to be all-inclusive. Who would want to see a film like that? What we focused on is a small part of the South, but it’s also a special part, the part that has changed the rest of the world forever, and given us the musical culture that underpins so much of the stuff we listen to today—so much of it coming out from those tiny little wooden churches, so long ago! At least, that’s our fanciful little theory. All we wanted to do was to find out if there was any of that creative spirit still there, if there was something in the land itself, and the poor rural community that engendered it.

And there is, but it may well disappear under the floods of the homogenizing “New South.” The film may be a time capsule, or like those African villages sitting at the bottom of the Aswan Lake after they built the dam.

Preview the Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus trailer