A 'Black-White' Missionary on the Imperial Stage:

William H. Sheppard and Middle-Class Black Manhood

John G. Turner

Department of History

University of South Alabama

When William M. Morrison first arrived in the Belgian Congo as a missionary in 1897, he observed with great interest his colleague William Sheppard conduct a Sunday chapel meeting. “Mr. Sheppard is to preach,” Morrison wrote, “and whenever he lifts his hand there is silence, whenever he speaks there is the closest attention.” Both Morrison and Sheppard were missionaries for the southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS), and they were both from western Virginia. Yet there was one prominent difference between them: Sheppard was black, and Morrison was white. Sheppard had already served for seven years in the Congo and had perfected his ability to speak the local dialect. Morrison noted that when Sheppard finished his “impressive sermon,” six people came forward to be baptized. Although it was unusual for a white southerner in the 1890s to praise a black man in terms that evoke power, leadership, and manliness, Morrison marveled at his colleague's performance: “he is a great chief, a prince, and apostle among this people.”

[1]

Twelve years later, Sheppard resigned from the mission when accused of multiple extramarital affairs, one of which resulted in the birth of a son whom Sheppard left behind in the Congo. After Sheppard returned to his native Virginia, a resident of his hometown commented that Sheppard “was such a good darky; when he returned from Africa he remembered his place and came to the backdoor.” Similarly, after Sheppard spoke in the pulpit of a local Presbyterian church, an affluent white congregant invited him to a dinner reception. She seated Sheppard on the back porch, which was adjacent to the dining room in which the other guests ate. Through a raised window, Sheppard answered questions about his experiences in the Congo.

[2]

Sheppard's quiet concessions to southern racial etiquette fit uneasily with his public image as a missionary celebrity who symbolized a more robust black manhood in the late 1800s and early 1900s. While abroad, Sheppard made contact with a Congolese kingdom previously isolated from western colonists, uncovered and publicized colonial abuses, and won his acquittal at a libel trial instigated by a Belgian rubber company. On his speaking tours, he held both white and black audiences spellbound with his tales of cannibals, vicious beasts, colonial soldiers, and his own courageous and athletic feats. When Sheppard stepped off the stage or away from the pulpit, however, white southerners no longer saw him as an “apostle” or “chief” but instead viewed him merely as a “darky.”

Sheppard has been the subject of two recent biographers, William E. Phipps and Pagan Kennedy, both of whom ably document Sheppard's colorful years in the Congo.

[3]

Unfortunately, Sheppard left behind few windows into his interior life. His published writings and what little correspondence exists describe his missionary adventures in a manner that reveals little about his own opinions and emotions. At times, he seems to play a bit part in a larger drama dominated by white patrons, white missionary colleagues, colonial mercenaries, and native Africans. On many topics of interest to historians and biographers, Sheppard remains silent. Sheppard never voiced his feelings about race in the United States. Not surprisingly, he never referred to his extramarital affairs or his abandoned son. Sheppard frequently mentioned his reliance upon prayer and his belief in God's protection during his adventures, and he clearly enjoyed preaching to native audiences. Yet Sheppard never detailed the formative experiences of his faith or discussed theological matters, such as the question of salvation for native Africans who never heard the Christian Gospel.

The different constructions of manhood and masculinity that appear throughout Sheppard's career shed further light on his enigmatic personality and on middle-class black manhood at the turn of the twentieth century.

[4]

Sheppard cultivated a late-Victorian “civilized” manhood early in his career, adopted a more “primitive” and robust masculinity as an “imperial male,” and then returned to dignified domesticity after his resignation from the mission field. For Sheppard, masculinity was a series of performances, and his performances depended upon the setting and audience he faced. If Sheppard on a number of occasions remade himself, he did not simply choose between a variety of available “masculinities.” Instead, his choices reflect what R. W. Connell has termed the “hard compulsions under which gender configurations are formed.”

[5]

Sheppard's various masculine personas suggest that in addition to analyzing how men and women described ideal male characteristics and practices, historians of gender must pay careful attention to the ways that dynamics of power – between whites and blacks and between men and women –shaped and constrained constructions of manhood. On the stage, Sheppard posed as the “King of Huntsmen,” but off the stage he found himself pushed back into the subservient, domestic roles that his southern white patrons deemed more appropriate for black men.

VICTORIAN MANHOOD IN THE CONGO

William Henry Sheppard was born in March 1865 in Waynesboro, a small town in western Virginia. Sheppard's mother, a “dark mulatto,” had been born free; his father's status at birth is unclear. His father was a barber, and his mother worked as a “bath maid” at a resort in Warm Springs.

[6]

When Sheppard published his memoirs in 1917, his father – also William Henry Sheppard – was still living.

[7]

He briefly discusses the role of both his father and mother in his religious upbringing, commenting that his father led “family prayers” and was the “sexton” – probably a caretaker – for the First Presbyterian Church of Waynesboro. It is clear from the account, however, that Sheppard's deeper affection was for his “dear mother,” Fannie Sheppard, who “in putting me to bed would kneel and pray aloud with me . . . scratch my back … and then put me snugly to bed.” He also praises his mother for never turning “anyone from her door who came begging, whether white or colored.”

[8]

In his youth, Sheppard attended a predominantly white Presbyterian church, and as the only “colored” child he received Sunday school instruction by himself, apart from the white children.

[9]

In postbellum America, blacks achieved middle-class status not primarily through the accumulation of wealth but rather through a constellation of factors: occupation, complexion, church membership, and the free or slave status of ancestors. Barbering was a typical middle-class occupation, and Presbyterian church membership was another indication of middle-class status.

[10]

Sheppard, a mixed-race, Presbyterian minister, therefore became a quintessential exemplar of the black middle class at the turn of the twentieth century.

In Sheppard's adolescence and early adulthood, a series of white men eclipsed his father as paternal figures. Sheppard repeatedly cultivated relationships with white patrons and effusively praised their wisdom and character. Around the age of ten, Sheppard moved to live with an aunt in nearby Staunton, where he worked for a white dentist, S. H. Henkel. Sheppard formed a lifelong attachment to Henkel, whom he regularly wrote while living in the Congo. In 1880, he enrolled at Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute. Shortly after his arrival, Sheppard took night classes from Booker T. Washington, who had graduated from Hampton in 1875.

[11]

Much like Washington, Sheppard expressed a striking admiration for Samuel Armstrong, Hampton's white founder and president. “General Armstrong,” Sheppard later wrote, “was my ideal of manhood.” He even referred to himself as “one of General Armstrong's children.” Sheppard admired “his erect carriage, deep, penetrating eyes, pleasant smiles, and kindly disposition,” and he lauded Armstrong as “a great, tender-hearted father to us all.” “He was a man,” Sheppard proclaimed in a 1915 address at Hampton, “to inspire boys to be men – to look up, to look out, and to face the world.” He also credited Armstrong with creating an institution that took young black men in a state of ignorance and superstition, gave them education, and pointed them “to the Lamb of God.”

[12]

Later generations of black Americans resented the paternalism of white men like Armstrong and their advocacy of manual education. Although Sheppard surely found it in his best interest to warmly praise Hampton's founder, he also appears – again like Washington – to have been a genuine admirer.

[13]

Similarly, Sheppard developed a close attachment to H. B. Frissell, Hampton's chaplain and Armstrong's successor as president of the institute. Sheppard helped Frissell establish a Sunday School mission at Slabtown, an impoverished black community near Hampton. Sheppard praised Frissell as “one of the humblest and most consecrated Christian gentlemen I ever knew,” and he credited Frissell with instilling in him a concern for “the poor, destitute and forgotten people” of the world.

[14]

After his graduation from Hampton, Sheppard attended the Tuscaloosa Theological Institute (now Stillman College) and was ordained in 1888 by the PCUS. Established in 1865, the southern Presbyterian denomination included a small minority of black members and a tiny group of black ministers and churches.

[15]

After brief pastorates in Tuscaloosa and Atlanta, Sheppard applied for missionary work in Africa. Black American interest in Africa grew in the late 1800s, partly because of a modest revival of emigrationist sentiment after the end of Reconstruction.

[16]

He later attributed his desire to serve in Africa to a “beautiful [white] Christian lady” who told him “while still a barefoot boy” that she hoped he would “go to Africa as a missionary.” Moreover, Sheppard reported that both his presbytery and his seminary asked him if he would be willing to go to Africa as a missionary.

[17]

Although his inner motivations remain unknown, the fact that he received so much encouragement from white Presbyterians indicates the denomination's growing interest in African missions.

The southern Presbyterian hierarchy had mixed feelings about commissioning black Americans as missionaries to Africa. J. Leighton Wilson, the first secretary of the church's Foreign Missions Committee, had himself worked for twenty years as a missionary in West Africa. He concluded that the region was a “white man's grave” but postulated that black Americans would survive the ravages of tropical diseases more readily than whites.

[18]

This conviction – and the belief that Americans of African descent would prove effective missionaries in their ancestral homelands – helped persuade a number of predominantly white denominations to send black missionaries to Africa in the late nineteenth century.

[19]

Some whites also supported black missionaries because they hoped they would spur black emigration to Africa. Other Presbyterian leaders worried that black Americans would quickly degenerate into barbarism and lasciviousness in Africa. Charles A. Stillman, the founder of the institute at which Sheppard received his theological training, feared that single black men in particular would debauch the native maidens.

[20]

In both 1888 and 1889, Sheppard implored the PCUS Foreign Missions Committee to send him to Africa, but southern Presbyterian officials refused to place him in the mission field alone and without white supervision.

[21]

Fortunately for Sheppard, a young white minister, Samuel Lapsley, also expressed interest in African missions in 1889. Lapsley, the son of an Alabama judge and former slaveholder, had recently graduated from McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. In 1890, the denomination sent Sheppard and Lapsley to establish an outpost in the Congo.

From the start, Sheppard and Lapsley developed a warm friendship. Lapsley expressed some anxiety over how others on their ship would treat his black colleague. Yet during an extended stay in London, where they obtained provisions, Lapsley marveled at the nonchalance with which the British treated interracial interactions. Once the pair arrived in Africa, the very different dynamics of the Belgian Congo destabilized Lapsley's approach to race. At times, he apparently thought of Sheppard as white. Lapsley once referred to Sheppard and Ernest Stache, a Belgian trader, as “the two white men.”

[22]

Lapsley and Sheppard discarded southern racial etiquette and prayed, hunted, explored, and grew feverish together. In a letter home, Lapsley praised Sheppard as “a true man and a gentleman.”

[23]

Lapsley frequently professed amazement at his partner's ability to kill hippos, barter with the natives, and steer their boats away from danger.

Shortly after his arrival in the Congo, Sheppard noted his happiness to have come to “the country of my forefathers.”

[24]

He forthrightly claimed his kinship with African natives. When he and Lapsley discerned that most natives – not surprisingly – had no knowledge of Christ, Sheppard lamented, “how blind my people are.”

[25]

Many native Congolese were undoubtedly surprised to see a black missionary. On the basis of his western clothing, they named Sheppard the “black white man,” literally “black man with [western] clothes.”

[26]

Sheppard's sense of identification with Africans did not prevent him from expressing great sorrow at the state of African society. Upon setting foot on the “Dark Continent,” Sheppard commented on “the curses of Africa” and was “glad to be in this heathen land to preach Christ to dying thousands.”

[27]

As the two missionaries made their initial explorations, Sheppard bemoaned “how deeply in superstition and vice have my people fallen!” He detested their warfare, their beheading of slaves, their crimes, and their drunkenness. Sheppard expressed himself “thankful” that he and Lapsley “were born in a Christian land, and taught at the knees of very dear mothers to know Him, whom to know is life.”

[28]

Sheppard pronounced his heart “saddened on account of those [Africans] who knew Him not.”

[29]

Sheppard and Lapsley made some rather awkward attempts to evangelize native villages but hoped for greatest success once they had established a mission station.

While in the Congo, Sheppard reflected not only on the African natives he met but also on the state of Americans of African descent. In late 1891, Sheppard wrote a letter to the Indianapolis Freeman, a black newspaper which he read while abroad. The letter gives clues to his early conception of black manhood. He urged the black American man to “work out mentally, morally, and manly, whatever good he might obtain.” Sheppard identified “duty” as the “watch word” of “Afro-Americans,” as something “expected of every man.” Much as Samuel Armstrong might have done, Sheppard urged black men to “continue an unrelenting effort, till the highest civilization attainable by man is reached.”

[30]

|

| William Sheppard in an early photograph, courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society, Presbyterian Church (USA) (Philadelphia, PA). |

Many scholars have criticized the black middle class of Sheppard's day for cultivating Victorian respectability as a means of distancing itself from the “black masses.”[31] There was, however, a positive sense of Christian mission in Sheppard's emphasis on duty and in his praise of figures like Armstrong – an understanding of manhood based not only on character in terms of personal respectability but also on extending the blessings of education and character to others. For Sheppard, that sense of responsibility included a desire to bring what he perceived to be the benefits of Christianity and civilization to colonial Africa. Sheppard demonstrated a number of traits typically associated with the late-nineteenth-century black middle class: a belief in education and hard work, white patronage, and an emphasis on duty and benevolence. Early in his career, Sheppard posed as the respectable Victorian gentleman in photographs that suggested erudition, self-control, and virtue. At a time when white Americans condemned black men as uneducated, lascivious, and only a few steps removed from barbarism, middle-class black men like Sheppard cultivated Victorian respectability partly as a means of gaining greater acceptance in a white-dominated society. Even when he later adopted different representations of manhood, Sheppard always understood the significance of respectability and virtue as a necessary counterpoint to white stereotypes of black men.

“THE KING OF HUNTSMEN”

Although he continued to present himself as a Victorian gentleman in certain settings, Sheppard's masculinity evolved in the Congo. As he operated with increased autonomy in the Congo, he became an “imperial male” who embraced elements of African culture, opposed colonial abuses, and portrayed himself as a robust and athletic “soldier-missionary.”

[32]

Once he overcame his initial culture shock, Sheppard demonstrated an unusually positive stance towards native Africans. He reacted with horror towards a group of cannibals, but he became entranced with the culture of the Kuba (or Bakuba) people. Sheppard and Lapsley were both impressed with this “most artistic race.”

[33]

Sheppard praised their beautiful artwork, their monogamous marriages (with the exception of the king), and their industry. The two Presbyterian missionaries intended to explore the Kuba country in 1892, although Sheppard reported that numerous white traders and Belgian officials encouraged the two missionaries to discard their plan. Evidently, Luckenga, king of the Kuba people, had long refused contact with white traders and threatened to kill anyone who helped a westerner reach his capital. Having befriended a number of Kuba traders by offering them hippopotamus meat, the two decided to risk the journey. Lapsley, however, died of a fever in May 1892. Sheppard, having already spent several months learning the Kuba dialect, resolved to journey to the Kuba capital accompanied by several of his native friends.

Sheppard devised an ingenious and humorous plan for penetrating the Kuba kingdom and reaching its “forbidden” capital. Upon reaching the last Kuba village known to him, he followed one of the villagers heading to the next marketplace and moved closer to the capital. At each village he reached, he told the inhabitants that he wanted to buy eggs, and when the village ran out of eggs, the chief allowed one of Sheppard's native companions to follow a villager to the next marketplace. “For three months,” Sheppard later recounted, “we did nothing but buy and eat eggs.”

[34]

Along the way, Sheppard preached the gospel at each village and perfected his knowledge of the Kuba language. Eventually, the king discovered his intrusion, but the king's council – citing Sheppard's fluency in the language – proclaimed him to be one of the king's deceased relatives. The king welcomed Sheppard to the forbidden capital, where he evangelized for four months without success and recorded his observations of Kuba culture.

[35]

He also discovered a lake previously unknown to westerners, which combined with his exploits in reaching the capital earned him membership in London's Royal Geographical Society.

Sheppard returned to the United States on furlough in 1893 and gave a series of spell-binding lectures on his exploration of the Kuba kingdom, stressing his reliance upon God in the face of looming death. Sheppard also married Lucy Gannt while on furlough.

[36]

The couple had become engaged sometime during Sheppard's years at Stillman. Gannt, like Sheppard, was of mixed racial descent. She taught school for six years in Birmingham while her fiancé worked as a pastor and then disappeared into the African jungle. Sheppard cabled her in 1893 from London and informed her that he would be in the United States soon and would visit her. Gannt must have gained some sense of Sheppard's growing capacity for self-promotion when he spoke at a Florida school the day before their wedding. Sheppard described his African exploits and then informed the children that “[t]he man who did these things is to be married tomorrow right here in your own city.”

[37]

The February 1894 wedding was the first of many times that Sheppard's expansive personality cast his talented wife into the background.

Sheppard brought Lucy and several other black American missionaries back to the Congo mission in 1894. Several white missionaries had arrived during Sheppard's leave of absence, and the mission gradually flourished as a steady stream of both white and black missionaries arrived in the Congo. One white missionary, William M. Morrison, became the dominant force within the mission within several years after his 1897 arrival. Morrison ran the mission's main station at Luebo, while Sheppard provided most of the leadership for the Ibanj station, located on the outskirts of the Kuba kingdom.

After his return from his 1893-94 furlough, Sheppard focused his work on the Kuba people. Despite Sheppard's sense of identification with Africans and admiration for Kuba culture, he in several respects embraced the style of the colonial imperial male. Like many white colonists and missionaries, Sheppard portrayed himself as a vehicle through which civilization might come to benighted natives. In particular, he worked hard to convert the Kuba, especially the Kuba nobility. Both Phipps and Kennedy anachronistically portray Sheppard as a missionary interested more in cultural understanding and social justice than in conversion and church membership. Sheppard did devote much of his time to a wide variety of activities: charity, social justice, linguistics, and the pursuit of friendship and adventure. Nevertheless, he strongly believed that the Kuba – regardless of any positive cultural traits – needed the gospel. “Nothing remains to be taught them,” Sheppard insisted, “but the gospel, so superior is their intelligence.”

[38]

Though he spoke little about the dangers of hell, Sheppard mourned over those Africans who “died without knowing anything about the Lord Jesus Christ coming into the world to seek and save the lost.”

[39]

He carefully documented and praised conversions throughout his career and cared deeply about the progress of the churches the mission helped plant in the Congo.

Furthermore, Sheppard promoted western morals, education, and ideals. When Sheppard met a local king soon after arriving in the Congo, he commented that the king “has not learned to wear pants, hat, or shoes yet.”

[40]

Although he demonstrated more sympathy for native culture than most white and black missionaries, Sheppard still routinely denounced polygamy and what he perceived to be ignorance. He and the other missionaries sought to promote monogamous marriages, eliminate “superstitious” practices, and build model settlements with western-style homes. Sheppard also devoted considerable effort to stamping out local injustices. In 1906, he proudly reported that the mission had built a church “on the famous spot where from time immemorial the accused witches have had to be tested by drinking poison.”

[41]

|

| William Morrison, Kuba witnesses from libel trial, and William H. Sheppard. Courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society. |

While Sheppard was an agent of western civilization, he also – both implicitly and explicitly – critiqued white American understandings of the imperial enterprise. Simply by being a black agent of western civilization, Sheppard called into question the standard assumption of most white American missionaries that connected whiteness and the Anglo-Saxon “race” with civilization.

[42]

He also explicitly critiqued western – or at least Belgian – colonialism and civilization. In 1899, he became embroiled in controversy because of a dramatic encounter with colonial atrocities. Natives from a neighboring region came to Ibanj and urged Sheppard to stop a raid by a group of cannibalistic warriors, the Zappo Zaps, who were employed by the Belgian authorities to collect tribute. They had plundered and razed more than a dozen villages in the Kassai region.

[43]

Sheppard was initially reluctant to investigate matters because he feared being killed himself. “It is just as if I were to take a rope,” he wrote, “and go out behind the house and hang myself.”

[44]

Orders soon came from Morrison, however, commissioning Sheppard to investigate and stop the raid. Fortunately, Sheppard met a Zappo Zap man whose life he had saved two years before, and he was allowed to enter the cannibals' camp and discuss the raid with their chief, who explained that his people were acting on behalf of the state and the rubber companies. In the camp, he discovered partly eaten corpses and eighty-one severed right hands. “These were to have been carried up also to the state post to show how many of the natives had failed to bring in the rubber required by the state,” Sheppard reported.

[45]

The state used the threat of terror to extort the collection of rubber by natives, who saw their villages burned if they failed to produce the required tribute. Sheppard and his colleagues managed to free sixty-two captured women. Shortly thereafter, Lachlan Vass, a white Presbyterian missionary, visited the scene and confirmed Sheppard's gruesome account. Morrison took Sheppard's report to the state officials – who refused to investigate – and publicized the atrocities in missionary periodicals.

[46]

While on another furlough in the United States during much of 1904 and 1905, Sheppard spoke out against these and the many other grim horrors he witnessed in the Congo. Moreover, he questioned Belgium's claim to be a civilized nation. When Sheppard discovered the rubber atrocities at the Zappo-Zap stockade, he noted that the Belgians had employed the “cannibals.” “You would be surprised to know what civilized nation's flag it was…,” Sheppard commented. “That this tribe is in the pay of the Belgian state officers,” he stated elsewhere, “adds to the natural depravity of savage ignorance the cruelty of civilized (?) greed.”

[47]

A number of black Americans of the era criticized Anglo-Saxon claims to civilization by portraying “civilizing” Anglo-Saxons as rapacious, domineering, and materialistic.

[48]

Sheppard similarly critiqued the Belgian capitalists and colonialists who were robbing the Congolese of their natural resources and forcing them into an abject state of economic slavery.

In 1906, Morrison published a poignant article by Sheppard in the Kasai Herald, the mission's periodical. In his article, Sheppard described the devastation that the Kasai Company – the state-sponsored firm that monopolized the rubber trade in the Congo basin – had wrought on Kuba society during the previous few years:

Their farms are growing up in weeds and jungle, their king is practically a slave, their houses now are mostly only half-built single rooms and are much neglected. The streets of their towns are not clean and well swept, as they once were. Even their children cry for bread.

Why this change? You have it in a few words. There are armed sentries of chartered trading companies, who force the men and women to spend most of their days and nights in the forests making rubber, and the price they receive is so meager that they cannot live upon it. In the majority of the villages these people have not time to listen to the Gospel story, or give an answer concerning their soul's salvation. Looking upon the changed scene now, one can only join with them in their groans as they must say: “Our burdens are greater than we can bear.”

[49]

When Sheppard and Morrison refused to retract the article, the Kasai Company sued Sheppard for defamation and injury in 1908. The court in the capital of Leopoldville dismissed the charges against Morrison, but Sheppard's case proceeded. After considerable pressure from the U.S. State Department and a heated trial, Sheppard was acquitted in October 1909. The judge took the expedient route of declaring Sheppard to have had no malicious intent in composing the article and thus avoided investigating the truth of the claims.

[50]

Nevertheless, the activities of Sheppard and Morrison – along with several reform groups on both sides of the Atlantic – helped pressure the Belgian Parliament to annex the Congo and remove it from the personal domain of King Leopold. Although freedom for the Congolese peoples remained distant, conditions in the colony did improve somewhat after the annexation.

[51]

Even as Sheppard gained fame for opposing colonial atrocities, in his talks and articles he primarily portrayed himself as a robust, athletic adventurer. During a 1905 talk at the Tuskegee Institute, he recounted his initial adventures with Lapsley, his hunting proficiency, and his crafty journey to the Bakuba capital, but spoke only briefly of the atrocities.

[52]

Despite his prominent role in the campaign against Belgian atrocities and his successful evangelistic work among the Kuba people, Sheppard left audiences with the impression that he primarily spent his time hunting and exploring. An article in the Boston Herald reported Sheppard's acquittal from the libel charge. Telling of his early association with Lapsley, the paper concluded that “President Roosevelt has had no such hunting adventures as befell these two missionaries” and noted that they had “killed 36 hippopotami, two elephants, and many crocodiles” while making five narrow escapes from “savages.”

[53]

Whenever Sheppard returned to the United States on furlough, he carted around massive amounts of Congolese art and weaponry, which he often brandished during his lectures.

[54]

As an African explorer and hunter, Sheppard symbolized aggression, strength, and courage – traits rarely associated with black Americans in the Jim Crow South.

In the style of an imperial male, Sheppard loved posing in his pith helmet and clean white clothing. In one such picture he holds the carcass of a deadly boa constrictor in front of a group of natives. Sheppard, who dominates the picture and relegates his African friends to the background, appears as a physically and culturally superior protector of native Africans. With obvious pride, he wrote his former patron S. H. Henkel that a group of Congolese had dubbed him the “king of huntsmen.”

[55]

Rather than stress his gentleness and virtuous character, he now emphasized his athletic prowess, his physical protection of the Congolese and his white companions, and his love of the jungle. One church advertised Sheppard as “Black Livingstone,” recalling the English explorer and missionary David Livingstone.

[56]

|

| William H. Sheppard with snake in the Belgian Congo , n.d. Courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society. |

By becoming “Black Livingstone,” Sheppard departed from the middle-class black masculinity typical of his era, but he painstakingly accepted the interracial standards of the Jim Crow South. Sheppard was deferential to whites. When he spoke of his missionary work, Sheppard made clear the preeminent role of his late white colleague Samuel Lapsley. In his speeches and articles, he routinely praised Lapsley's piety, concern for the natives, and self-sacrificial death. He probably discerned that white audiences – even if they thrilled to see “Black Livingstone” – also enjoyed hearing stories about the pious white martyr. Sheppard continued to repeat the same material decades after Lapsley's 1892 death. He even put Lapsley's photograph on the frontispiece of his 1917 memoir, Presbyterian Pioneers in the Congo. Black audiences easily detected and saw through this sort of deference. An article in the Tuskegee Student in 1905 observed that “[w]ith remarkable tact he [Sheppard] conveyed the impression that it was Mr. Lapsley who was ever to the fore in the missionary work and that he … was only a factor in his assistance.” “It is well known however,” the author noted, “that he labored side by side with Mr. Lapsley and that they shared hardships in common.”

[57]

Accounts by both Sheppard and Lapsley indicate that Sheppard was far more than an assistant to Lapsley. They certainly appear to have worked together closely, if not as equals, and Lapsley makes it clear that he relied heavily on Sheppard's resourcefulness and ability to interact with the Congolese. When other white missionaries appeared on the scene in later years, Sheppard still operated in a largely independent manner. In at least one year, his name appeared at the top of the mission's hierarchy, above the names of his white associates.

[58]

In his published reports, however, he indicated that he deferred to his white fellow missionaries. For instance, he stated that he investigated the atrocities only after receiving orders from Morrison. Sheppard employed “remarkable tact” to make sure that he appeared to be a humble worker who did not challenge the superiority of his white colleagues.

Even Sheppard's critiques of colonial injustices were somewhat hesitant and muted. He felt that it would be best if he took a secondary role in the effort to publicize the atrocities. “Being a colored man,” Sheppard explained to Vass, “I would not be understood criticizing a white government before white people.”

[59]

In 1904, the Belgian ambassador to the United States, Baron Moncheur, left a meeting with Sheppard convinced that Sheppard would not have protested the atrocities without Morrison's direction.

[60]

In later years, Sheppard somewhat apologetically insisted that he did not blame Belgium for the horrors. In a 1915 speech at Hampton, he maintained that “the Belgians” had not “sanctioned” “the murder of the people in the Congo.”

[61]

Sheppard clearly preferred to thrill audiences with stories about his adventures rather than keep the focus on a human rights campaign that could disturb his carefully maintained relationships with white Americans.

Sheppard's missionary persona as “the king of huntsmen” suggests the appeal of muscular Christianity in the black church and indicates that a black masculine fascination with the “primitive” was emerging well before the Harlem renaissance of the 1920s.

[62]

Apart from direct white control in the Congo and as a missionary celebrity, Sheppard operated with enough distance from white authority to cultivate a more athletic and robust construction of black masculinity.

[63]

Moreover, African American missions to Africa fostered a fascination with the primitive, which Sheppard furthered through his tales of native society and his displays of African art and weaponry. Interestingly, despite this different construction of masculinity, Sheppard's new persona coalesced rather easily with late-Victorian respectability.

[64]

During his years in the Congo, Sheppard married, began a family, and worked hard to build a church in Africa. Moreover, even as “Black Livingstone,” Sheppard still subordinated himself to his white colleagues and worked hard to avoid offending white sensibilities. At the peak of his fame, Sheppard juggled these different masculine personas successfully. Sheppard's delicate balancing act, however, fell apart when he became more directly subject to white oversight, authority, and discipline.

THE CHILDREN'S FRIEND

Sheppard's 1909 acquittal marked the high point of his missionary career. After the trial, he returned to his Ibanj mission station. “We are happy, so happy away over here in the remotest part of the planet,” Sheppard had written to a former Virginia patron earlier that year.

[65]

Yet only two months after the trial ended Sheppard resigned from the mission, ostensibly for health reasons. The true reason for his departure, however, stemmed from a series of extramarital affairs between Sheppard and Congolese women.

[66]

Early in his marriage to Lucy Gannt, Sheppard wrote articles for missionary journals that portrayed a happily married couple. Lucy made the journey to the Congo while pregnant with their first child. William oversaw the construction of a five-room house, which Lucy decorated based on advice from Ladies' Home Journal. She taught basic home economics to Congolese boys and girls, including lessons in laundry and cooking. She also persuaded William to allow her to join him on his second visit to the Kuba capital. “I have found out a few things since marrying,” he jested. “[W]hen women set their heads to a good work, they are not easily dissuaded.”

[67]

The Sheppards, despite Lucy's pregnancy, apparently enjoyed the journey together. William took great pleasure in introducing his wife to the Kuba king and featured her in his description of events.

[68]

During a 1904-05 lecture tour, Lucy joined William for some of his engagements, usually singing a hymn in both English and an African dialect. Occasionally, groups invited her to speak on her own. She spoke and sang at the Monteagle Chautauqua meeting in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee, and a white Presbyterian minister, D. C. Rankin, publicized the details of her talk. Rankin called her “the mother of the mission.” According to Rankin, Lucy taught in the mission schools, helped “clothe and civilize” refugees, led the singing during church services, and nursed fellow missionaries, including “young men from the most cultured white families of the South.” She even took over as mission treasurer during a time when the men were absent or sick. Rankin described the Sheppards' marriage as “one of the romances of modern missions.”

[69]

Behind the scenes, however, there was more trauma and distress than romance. The Sheppards' first two children died in Africa, one in early 1895 and the other a year or two later. After Lucy gave birth to a third child, she took the baby girl back to the United States in 1898. During her furlough, William had the first of an indeterminate number of affairs with African women. Many years later, Sheppard made a confession before the Presbytery of Atlanta. “Sometime in the years 1898-1899,” he stated in 1910, “while my wife was at home I was left alone in my work, [and] I fell, under the temptation to which I was subjected in my relations with one of the native women at Ibanj Station and was guilty of the sin of adultery." At the time of his initial confession, Sheppard denied other rumors of infidelity, but a year later he confessed to having engaged in three additional affairs between 1906 and 1910.

[70]

One of the affairs produced a son – named Shepete, after his father – in whose upbringing Sheppard played little if any role. Phipps suggests that some missionaries believed that Sheppard left a number of children behind.

[71]

Evidently, there had been rumors of such problems for some years, and it is impossible to determine the extent of Sheppard's unfaithfulness. The glow certainly seemed to fade quickly from the Sheppards' marriage. After the early accounts of their joint trip to the Kuba capital, William rarely mentioned Lucy in his speeches or articles. Sheppard's colleagues referred far more often to Lucy than he did. Lucy became a largely invisible partner while her husband occupied the limelight.

[72]

Morrison took the leading role in communicating the mission's displeasure with Sheppard's behavior to denominational authorities. Samuel Chester, the executive secretary of the PCUS Foreign Missions Committee, met with Sheppard, cried with him, accepted his resignation, and expressed his satisfaction at Sheppard's partial confession. Sheppard's marriage and career survived his forced resignation from the mission, and the church did not severely sanction its missionary hero. Even after Sheppard's additional confessions, the Presbytery of Atlanta only suspended him for a year and did not make Sheppard's indiscretions public knowledge. As J. O. Reavis, another Presbyterian official, wrote Morrison, “only a few need know about the trouble at all.”

[73]

The church's handling of the case is somewhat curious. The timing of Sheppard's resignation – a mere two months after his acquittal – suggests that Sheppard's colleagues did not wish to press the matter while Sheppard played a visible role in the Congolese human rights campaign. Reavis's assurance of near secrecy reveals a concern for the reputation of the mission. At the same time as Morrison proceeded against Sheppard, he also corresponded with Chester about the alleged infidelities of two other black missionaries, Henry Hawkins and Joseph Phipps.

[74]

Hawkins had traveled with the Sheppards to the Congo in 1894, and Phipps had served with the mission for at least ten years. Hawkins, who evidently also fathered a child in the Congo, resigned about the same time Sheppard did.

[75]

The details of Phipps's case are unclear, but he evidently was also forced to leave.

[76]

Thus, the mission quickly lost most of its black male leadership at the instigation of its white male leadership. Kennedy speculates that Morrison was “given to episodes of paranoia,” disliked Sheppard's largely autonomous leadership of the Ibanj mission station, and envied Sheppard's fame and celebrity.

[77]

This is certainly possible, but Kennedy presents no evidence to support her assertions. Given the common stereotypes of black male sexuality, however, it seems reasonable to conclude that white men like Morrison were at least predisposed to take seriously charges of sexual improprieties against black men like Sheppard, Hawkins, and Phipps.

Both white and black missionaries – as well as other colonists in West Africa –engaged in sexual liaisons with African women. Samuel Verner, a white man who briefly worked with the Presbyterian mission in the late 1890s, fathered a child with a native mistress.

[78]

Lapsley wrote about his fascination with “a really beautiful woman, with pretty small mouth … and eyes like a gazelle, a modest and womanly and charming expression withal.”

[79]

There is no evidence that Lapsley entered into any sexual relationships in the Congo, but the litany of romances and affairs provides clear evidence that both white and black men found it difficult to maintain their Victorian mores overseas.

Sheppard's infidelity was thus not unusual. It does, nevertheless, suggest an additional aspect of his persona as an imperial male. In the Congo and on his speaking tours, Sheppard symbolized robust, masculine physicality. Throughout his career, though, Sheppard still retained an image of “civilized manliness” through his cultivation of respectability, his occasional displays of domesticity, and his mission to uplift African culture. Sheppard's extramarital affairs illustrate a private rejection – or at least transgression – of the Victorian respectability that he as a Presbyterian missionary could not publicly reject. In the Congo, away from southern racial dictates, he was free to be a hunter and a courageous fighter for African rights. Sheppard was also free to ignore the Victorian morality – white and black – that formed an integral part of black middle-class respectability and character. Sheppard's forced resignation, of course, demonstrated that Sheppard was only temporarily at liberty to disregard those constraints. Sheppard's liaisons also illustrate the more sinister aspects of the “imperial male” persona. Lucy Gannt Sheppard waited patiently while her fiancé explored Africa, lost two infants in the Congo, and then returned home in the wake of her husband's disgrace.

[80]

Sheppard, as a black American Presbyterian, served at the mercy of a white hierarchy. Yet as a male clergyman, he had considerably more access to power than his wife, the women with whom he had affairs, or his abandoned child.

Sheppard's moral shortcomings recall the fears of Charles Stillman – the founder of Sheppard's alma mater – that black missionaries would debauch the native maidens. Many white Americans portrayed black men as sexually unrestrained, licentious, and predisposed toward the rape of white women. Whites also alleged that a lack of sexual restraint made men of African descent “uncivilized.” Many black middle-class men sought to present themselves as virtuous and gentle in order to counter such negative stereotypes. In a sense, then, it is tragic that Sheppard's actions could not rebut the racist beliefs of men like Stillman. Several scholars have lambasted the black middle class of Sheppard's day for its false pretensions to Victorian virtue and sexual purity.

[81]

Sheppard praised the monogamy of the Kuba people while living more like the Kuba king. It is, however, worth considering that those false pretensions arose in the context of white stereotypes that misrepresented and distorted the masculinity and virtue of black and white men alike.

Sheppard's affairs ended an illustrious missionary career highlighted by his accomplished record as an explorer, evangelist, and champion of justice. After his suspension ended in 1912, he accepted a call to pastor Grace Presbyterian Church in Louisville and work in the Presbyterian Colored Mission, an urban ministry run by John Little. Little, a white Presbyterian minister, did not advocate racial equality.

[82]

He designed his programs not to encourage a generation of well-educated black leaders, but rather to provide blacks with religious training and some basic skills to enable them to work in subordinate positions to whites as “chauffeurs, janitors, workers in factories, laundresses, and cooks.”

[83]

Little did not invite blacks to serve on the board of the mission. He did not socialize with the Sheppards, although William's fame was largely responsible for the growth of the mission and church.

[84]

Starting from a base of around forty, Grace Presbyterian added sixty additional members during Sheppard's first year.

[85]

By 1926, the final year of Sheppard's active work as pastor, the congregation reported 334 members, nearly a tenfold increase in membership during Sheppard's tenure.

[86]

He suffered a stroke in late 1926, never fully recovered, and died in November 1927.

[87]

As always, Sheppard remained deferential towards southern racial etiquette during his Louisville pastorate. He often lectured at white church luncheons, but he agreed to leave after his talks so that the churches would not have to confront the nettlesome issue of segregated dining.

[88]

It seems that Sheppard's attitude pleased many whites. S. H. Chester commented upon Sheppard's return that “he has come back to us the same simple-hearted, humble, earnest Christian man that he was when first we sent him out.”

[89]

Other black leaders in Louisville, including some clergy, organized a NAACP chapter to fight a 1914 residential segregation ordinance. They also protested a 1924 ordinance that officially segregated the city's public parks.

[90]

Sheppard, however, never joined such efforts, and he apparently never spoke out against Jim Crow. The only hint we have of Sheppard's politics is one recorded instance in which he served as an informant for Booker T. Washington against W.E.B. Du Bois.

[91]

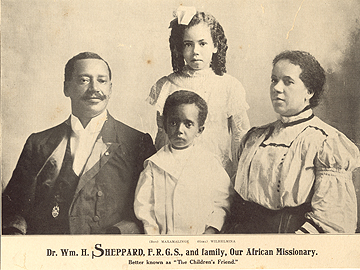

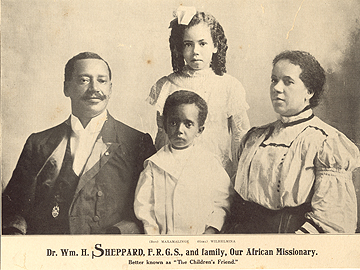

Once his fame dissipated, Sheppard could no longer play the role of “King of Huntsmen” or “Black Livingstone.” In his later years, Sheppard reassumed a Victorian middle-class manhood, presenting himself as a loving husband and father. A portrait taken of Sheppard with his wife and children shortly after his return to America refers to Sheppard as “Our African Missionary … Better known as ‘The Children's Friend.'”

[92]

Sheppard looks unusually solemn, especially in comparison with the broad grin that he wore in his hunting pictures. Given the circumstances surrounding his departure from the mission field, Sheppard's re-creation of himself as “The Children's Friend” represents an ironic twist in his constantly evolving masculinity. In an article published in the Louisville Courier-Journal, Anne M'Neilly White observed that Sheppard had moved from “Darkest Africa to Darkest Louisville” and perceived no difference between Americans of African descent and African natives. White found it remarkable that “a little pickaninny” had become a “Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of England.” Furthermore, White commented that Sheppard was “still in the prime of manhood, going about his work in the city of Louisville as quietly and as unostentatiously as if he had never carved a hippopotamus for a flank steak.”

[93]

He might have remained in “the prime of manhood,” but it was a different manhood than he had displayed in Africa. Retired from the mission field in segregated Louisville, Sheppard retreated to a dignified domesticity.

|

| William H. Sheppard and family, n.d. Courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society. |

Sheppard's multiple personas and shrouded personality suggest the difficulty scholars face in forming generalizations about fin-de-siècle black middle-class masculinity. Sheppard was certainly not the “beast” of the white imagination, but he was also not the Du Boisian dandy, not the combative Jack Johnson, and not simply the Washingtonian conservative.

[94]

Sheppard's many and at times contradictory masculine constructions suggest that for at least some middle-class blacks, masculinity was as much a series of performances as a cluster of ideals. Furthermore, Sheppard's masculinity depended largely on the setting he inhabited and the relative amount of autonomy he enjoyed. Sheppard found an opportunity to travel to a colony where race was an unstable category and he could operate with an autonomy virtually unthinkable for African Americans in the South. While in the Congo and as a celebrity missionary, he embraced a black version of muscular Christianity and provided an early example of the fascination with African culture and the primitive that later became more prominent in African American society. At the same time, Sheppard was unswervingly careful in negotiating the hazards of southern racial etiquette. His interactions with whites reveal a conscious desire to remain quiet and unostentatious, traits that helped him maintain a safe respectability but diminished the more robust masculinity he had embraced overseas.

At an 1895 Congress on Africa held at Gammon Theological Seminary in Atlanta, AME Bishop Henry McNeal Turner asserted that “there is no manhood future in the United States for the Negro.” “[H]e can never be a man – full, symmetrical and undwarfed,” Turner concluded.

[95]

Sheppard's career provides a stirring example of an African American man who temporarily escaped the conventions of southern racism, but his years in Louisville well illustrate Turner's lament. Sheppard carved out enough autonomy in the Congo to adopt a very different style of manhood than he displayed earlier in his career. In the end, however, his transgressions of Victorian respectability cost him his autonomy and forced him to abandon his robust masculine persona. Indeed, the viability of the celebrity personalities Sheppard adopted ultimately depended on the support of a white denomination and the cooperation of white missionary colleagues. For a respectable middle-class black man in the Jim Crow South, “Black Livingstone” and “The King of Huntsmen” could only exist as characters on the stage. Away from the mission field, “The Children's Friend” was his best available role. |