Take Away the Serpents from Us: The Sign of Serpent Handling and the Development of Southern Pentecostalism

Introduction 1

Few religious groups in the United States are more readily recognizable than serpent-handling Christians.2 Many Americans are familiar with grainy black and white photographs or jerky videos of sweaty, wild-eyed worshippers, who cram into hot, rundown rural churches where they proceed to speak in tongues, roll around on the floor, slather one another with oil, and fondle rattlesnakes, copperheads, and the rare king cobra. Sensational tales of death, endangered children, booze, and fanaticism abound in the popular media’s coverage of the practice.3 Serpent-handling Christians regularly appear as main characters in newspaper articles, novels, and television shows.4 Even in the academy, social scientists have a long history of taking up snake handlers as research subjects. Sociologists and psychologists frequently approach handlers as useful subjects that illustrate psychoanalytic, commitment, and role theories. 5

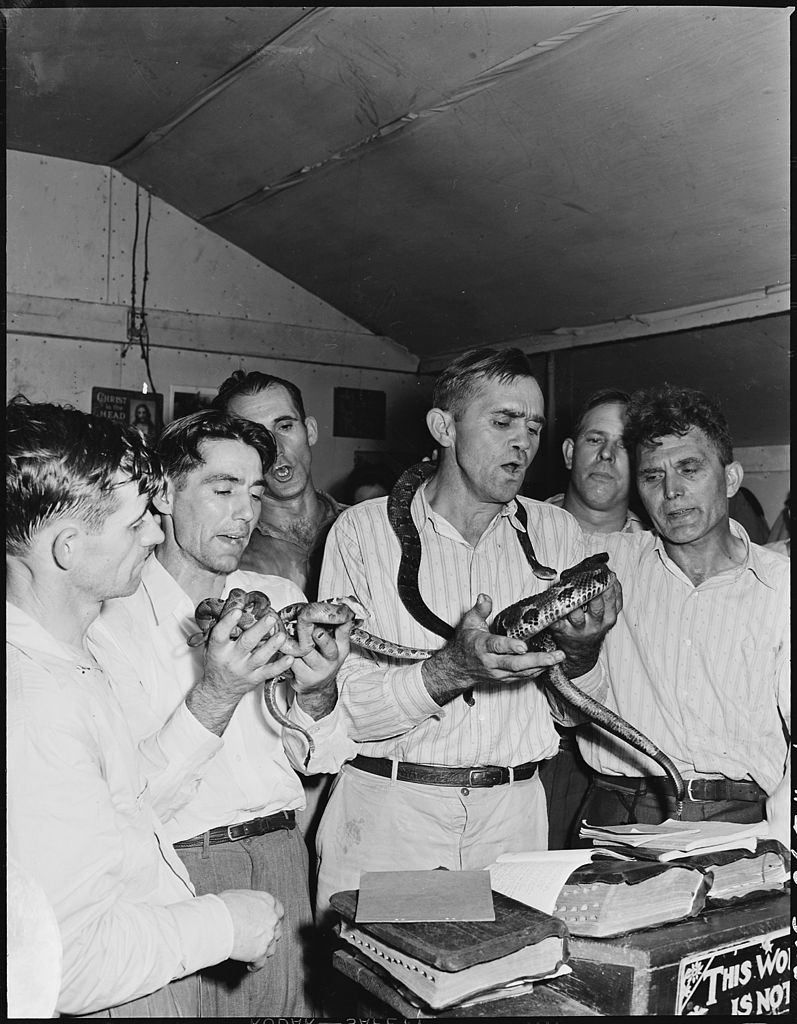

Snake Handling in Lejunior, Kentucky, September 15, 1946. Russell Lee, courtesy the National Archives and Records Administration.

Visual media, such as Russell Lee’s photography for the United States Department of Interior in the late 1940s, have solidified the iconic otherness of serpent handling for many Americans. The Interior Department hired Lee to record images of the living conditions in Kentucky’s coalfields. Lee’s work as part of the Medical Survey of the Bituminous Coal Industry (1946–1947), now in the public domain, circulate widely on the Internet and are available on may websites. Lee’s original caption to this photo read, “Handling of serpents, a part of the ceremony at the Pentecostal Church of God. This coal camp offers none of the modern types of amusement and many of the people attend the services of this church more for the mass excitement and emotionalism than because of belief in the tenets of this church. Lejunior, Harlan County, Kentucky, 09/15/1946.”

Despite the disproportional attention in popular media outlets and interest among social scientists, serpent-handling Christians remain relatively understudied by scholars of American religious history. While notable exceptions to this generalization exist, scholars in the humanities generally relegate serpent handlers to one or another subfield of study.6 Historians, for example, tend to portray handlers as a unique, nearly autonomous subset of the holiness-pentecostal movement.7 In the end, although many scholarly narratives recognize that serpent handling developed from the convergence of folk, holiness, and pentecostal traditions in the South, most scholarship represents serpent handling as a mysterious and more or less sui generis phenomenon in the historiography of American religion.

This essay reassesses serpent handling’s place in the history of the early holiness-pentecostal movement.8 It explores the problem the five signs enumerated in the Gospel of Mark 16:15–18—speaking in tongues, healing the sick, casting out demons, handling snakes, and drinking poison—posed for pentecostals in the South during the first half of the twentieth century. 9 Close readings of early twentieth-century printed sources from the holiness-pentecostal and secular presses indicate that authors and audiences viewed serpent handling as a new, innovative, and threatening religious practice. The arguments documented in these sources suggest that the identification of serpent handling as a specific practice limited to a small religious subgroup helped establish the boundaries of what today are generally recognized as legitimate pentecostal worship in the United States. Ultimately, these processes of socio-symbolic differentiation inside pentecostalism paralleled the legal construction of snake handlers as criminals whose bodies and behavior required regulation through ecclesiastic and state disciplinary mechanisms.

This historiographic reassessment of serpent handling moves through three distinct parts. First, the essay argues that serpent handling emerged as a problem for a number of religious groups in the South as the pentecostal revival spread into the region. Most significantly, under the oversight of A. J. Tomlinson (1865–1943), the Church of God, based in Cleveland, Tennessee, advocated for the handling of snakes while some of its early leaders directly engaged in the practice. As a result of the Church of God’s acceptance of the practice, other pentecostal-inspired groups in the South—most notably the Assemblies of God and the Pentecostal Holiness Church—also had to contend with the significance of handling snakes. Part one of this essay tracks how the Church of God used serpent handling to attack their rivals while other pentecostal groups warned their members to beware the fanatics in the Church of God. By highlighting efforts to embrace or reject serpent handling, part one explores how the practice helped create important boundaries between legitimate and extreme forms of worship within various church polities. The creation of these boundaries helped many pentecostals resist the imposition of pejorative designations such as “holy roller” to label all spirit-filled Christians. As pentecostal groups debated the validity of the controversial practices associated with Mark 16, they developed more precise categories for identifying different practices and theologies related to the Markan signs. This process of differentiation eventually led to the creation of snake or serpent handling as a distinct form of worship recognized by pentecostals and the wider American public.10

Part two of this essay traces the rejection of snake handling by the Church of God as it came into alignment with other major pentecostal denominations during the 1920s. Following a split with Tomlinson, the Church of God’s leaders adopted the logic of other interpreters who argued that the signs mentioned in Mark refer to the accidental handling of serpents. Leaders now dismissed those who willfully took up snakes as fanatics and showmen. Although nearly a decade passed before favorable references to serpent handling disappeared from church publications, most church leaders did eventually condemn the practice. The second part of the essay closes in the 1940s as Church of God leaders joined other major pentecostal bodies in calling for state authorities to criminalize snake handling.

Part three turns away from the pentecostal-holiness press to explore journalistic depictions of serpent handling recorded in non-church affiliated sources from the 1910s to the 1950s. From the 1910s through 1930s, the earliest stories in the popular press conflated serpent handling with holy roller and holiness worship to highlight the perceived absurdity and danger of the entire pentecostal revival in the South. By the 1940s and 1950s, however, this tendency to flatten pentecostal-holiness religious practices into a singular category gave way to reporting that pathologized snake handling as a unique aberration. Using concepts drawn from post-World War II anthropology and Cold War-era social sciences, journalists characterized serpent-handling Christians as brainwashed rural cultists who shared traits with other primitive religious groups found around the world. This later reporting coincided not only with the unanimous rejection of the practice by organized pentecostal churches, but also with state efforts to regulate the practice out of concern for public safety.

At no point does this essay suggest that all or even many holiness-pentecostal groups seriously considered serpent handling as a legitimate practice. In fact, there is little evidence in the historical record that any group other than the Church of God condoned the practice. The purpose of reconsidering the historiographic import of serpent handling is two-fold. First, early southern holiness-pentecostalism was an ad hoc, dynamic movement that emerged as people, interests, theologies, and bodily practices circulated through competing social institutions. Serpent handling—along with the Church of God’s attempt to appropriate it and the other churches’ steadfast work to reject it—was a manifestation of a particular moment in southern religious history. The practice of snake handling developed in the early twentieth century as a confluence of folk tradition, religious revival, and theological reflection on the signs listed in Mark 16. 11 Second, the eventual consensus among pentecostal denominations to reject the practice suggests that serpent handling played an important but unexplored role in creating popular distinctions in the ways some Americans imagined the limits of religion and its popular practice in the United States. Most notably, the rejection of serpent handling by most religious bodies paralleled the criminalization of certain forms of worship and contributed to popular imaginings of Appalachia as a regional and cultural “other” in the United States.

I. Holy Rollers and the Problem of Signs

Before delving into the problem of serpent handling as it emerged in the early pentecostal revival of the South, it is worth considering the place of the practice in historical scholarship. Since the 1970s, much of the scholarship on serpent handling has tended to frame the practice as marginalized and at odds with the prevailing theological trends and ritual practices that dominated holiness-pentecostalism in the early twentieth century. 12 For example, in a scare-quote laden section of the first edition of The Holiness-Pentecostal Movement in the United States (1971), Vinson Synan singled out the “cult of snake-handlers” as the “extremists” primarily responsible for the atmosphere of “prejudice, hostility, and suspicion that would mar the relationship of the early pentecostals to society at large.” 13 Synan dismissed the practice’s connection to the wider holiness-pentecostal milieu, arguing that it emerged spontaneously in “mountain sects which have no connection with the major pentecostal denominations.” 14 Similarly, Robert Mapes Anderson’s Vision of the Disinherited (1979) dismissed the “extreme phenomena” of snake and fire handling, which he argued were “restricted in practice to Pentecostals in the most backward and culturally isolated regions of the Ozarks and the lower Appalachians.” 15 Unlike Synan, Mapes conceded that some early pentecostal denominations recognized these practices, but he ultimately dismissed them as “sanctioned by time-honored folkways” that were not directly connected to the theological and social issues raised by the wider holiness-pentecostal revival. 16

More recent studies focusing on religion in Appalachia have given serpent handling more attention. Deborah Vansau McCauley’s Appalachian Mountain Religion (1995) dealt with serpent handling in order to correct popular misconceptions that have “elevated” it “to the position of being the primary representative of what is special and unique about ‘religion in Appalachia.’” 17 In contrast to McCauley’s corrective narrative, Randall J. Stephens’s The Fire Spreads (2008) situated the problem of serpent handling squarely within the context of controversies associated with the holiness-pentecostal revival of the first quarter of the twentieth century. Echoing Mapes, Stephens relegated serpent handling to “a small fraction of white southern pentecostals, isolated in the Appalachian Mountains and their foothills.” 18

This brief summary suggests that much of the historical literature on serpent handling rests on two basic assumptions about the practice: 1) generally, historians do not consider serpent handling to be an important component of the southern holiness-pentecostal revival; and, 2) when historians do address handling they often end their narratives by safely circumscribing the practice to the lower Appalachians: America’s imagined landscape of primordial otherness. 19 In contrast to this scholarly consensus, primary sources from the first half of the twentieth century suggest that the early pioneers of the holiness-pentecostal revival recognized serpent handling as a problem worthy of consideration. Many important publications of the holiness-pentecostal press—especially the Church of God’s The Church of God Evangel, the Stone Church’s The Latter Rain Evangel, and Assemblies of God’s The Pentecostal Evangel—discussed Mark 16: 15-18 extensively. 20 At the root of the controversy was a dispute over the various “signs” of baptism by the Holy Spirit—namely, speaking in tongues, healing the sick, casting out demons, handling snakes, and drinking poison—as indications of spiritual power. Within wider debates over the legitimacy of the Markan signs, serpent handling, for many church leaders and laypeople alike, was not simply an expression of primitive Appalachian folk culture. Rather, for some it was a modern symbol of God’s progressive, unfolding plan for humanity. For others it was a morbid circus trick that embodied the values of a sick modern culture enamored with individualism, showmanship, and media sensation that tarnished the public’s wider perception of the spreading revival. Either way, for many early pentecostals and their critics, the handling of poisonous snakes in religious meetings was distinctly modern and required explanation.

Church of God Elders Council, October 4-17, 1917. Seated: A. J. Tomlinson and Blanche Koon. Standing left to right: M.S. Lemons, T. S. Payne, T. L. McLain, F. J. Lee, Sam C. Perry, George T. Brouayer, E. J. Boehmer, J. B. Ellis, S. W. Latimer, S. O. Gillaspie, and M. S. Haynes. Courtesy Hal Bernard Dixon Jr. Pentecostal Research Center.

Of the fourteen prominent early leaders of the Church of God pictured, existing sources indicate that at least three were present during revivals in which serpents were handled: J. B. Ellis, George T. Brouayer, M. S. Lemons. Ellis and Lemons were critical of serpent handling, but ultimately accepted Tomlinson’s promotion of the practice until 1921. Brouayer, Tenessee State Overseer, is notable because he and Hensley led a revival during the Church of God’s 1915 General Assembly. Evangel accounts record that two of those pictured personally handled snakes during revivals: T. L. McLain and M. S. Haynes. Haynes, a Bishop in the church, helped Hensley conduct his infamous 1914 revival that helped solidify serpent handling’s place the in Church of God. Finally, Tomlinson, while there is no record he ever handled snakes, was the leading proponent of the practice in the church.

If there is an area where the sources line up with historical consensus, it is in terms of the number of snake handlers. The practice never captured the imagination—or the bodies—of the majority of Christians swept up in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. The population of serpent handlers has probably never amounted to more than a few thousand, and in the early days handlers likely numbered in the low hundreds. But this small number of serpent handlers generated a disproportionate amount of interest among leaders in the Church of God, one of the largest and most significant churches in the holiness-pentecostal revival. Between 1916 and 1932, many prominent leaders in the Church of God’s hierarchy actively handled serpents and many more wrote and spoke in defense of the practice. During this period, no less than seven State Overseers of the Church of God handled snakes during revival meetings. 21 Tomlinson, the church’s first General Overseer, developed a theological justification for the practice that many handlers reference to this day. Further, the Church of God’s initial acceptance of the practice led to conflict with other pentecostal bodies and became an important wedge issue Church of God ministers used to distinguish themselves from other pentecostals. At the same time, the development of wire news services ensured that handling would escape the constraints of the church that nurtured it to become a regional practice and a national curiosity. In short, much of the current scholarship on the holiness-pentecostal tradition in the South provides not only an insufficient assessment of the practice in the early history holiness-pentecostalism, but it also fails to consider how handling related to larger cultural trends in the United States, including popular imaginings of Appalachia as a site of regional otherness and normative conceptions of the limits of religious practice. The remainder of this essay seeks to outline how the contested explanations and justifications for handling poisonous snakes in religious meetings led to the creation of snake or serpent handling as a distinct form of worship both in the minds of pentecostals and in the minds of the wider American public.

Living Signboards

In the early twentieth century, many southern holiness-pentecostals understood baptism by the Holy Spirit in terms of a question Charles Fox Parham (1873–1929) posed to his Topeka-based Bethel Bible School students. In December 1900, he asked a small group of his students what “indisputable proof” of Holy Spirit baptism might look like. 22 After studying the second chapter of Acts, they all offered the same response: the proof of Holy Spirit baptism came when the ancient apostles “spoke with other tongues.” 23 Through the ministry of African-American holiness preacher William Joseph Seymour (1870–1922), the Topeka interpretation of the sign of tongues spread to a national—and eventually international—audience. Although nuances regarding the validity of certain experiences separated Seymour and Parham, the two men cultivated what would become a widely-held belief in pentecostalism: Spirit baptism is followed by clear and unmistakable signs that attest to its reality. In Los Angeles in 1906, the blind, soft-spoken Seymour initiated the raucous, emotionally charged Azusa Street Revival. It met three times a day, seven days a week, and lasted for three and one-half years. 24 Although the Los Angeles Times ridiculed Seymour’s “weird doctrine” of “the gift of tongues” as little more than “howlings” and “babel,” by the hundreds and then thousands, people adopted the “restoration of Pentecostal power” manifested in the embodied signs of the rapidly growing movement. 25

Emphasis on signs ensured that the early pentecostal movement developed into a “semeiocracy.” 26 It was a community ordered—at least partially—according to a regime of carefully cultivated bodily signs. These signs allowed the community to read the fact of one’s Holy Spirit baptism. While Parham’s students detected the proof of the third blessing of Spirit baptism in the “other tongues” described in Acts 2:1–4, early pentecostals also turned to Mark 16:15–18 for a fuller typography of the signs accompanying the Holy Spirit. Theologians John Christopher Thomas and Kimberly Ervin Alexander’s survey of pentecostal publications from the first two decades of the twentieth century revealed that “the earliest Pentecostals saw the Mark 16 text as a kind of litmus test for the authenticity of their experience.” 27 The text’s “unrivaled” position in the early movement guaranteed that the embodied signs it enumerated would become essential symbols of one’s status not only as a follower of Christ but also signified one’s relative stature within the emerging community. 28

Gaston B. Cashwell (1860–1916) played a pivotal role in bringing Seymour’s brand of pentecostal worship to the South and inadvertently influenced the development of serpent handling. Cashwell preached a message that synthesized the “second blessing” or “sanctification” of holiness with the “evidence” of speaking in other tongues. Cashwell’s message helped lay the theological and institutional foundation for the Pentecostal Holiness Church in the Carolinas. Further, Cashwell’s teachings had a direct influence on Tomlinson, then a leader of a small holiness group in the Unicoi Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina, which would become the Church of God. 29 After hearing Cashwell’s message, Tomlinson described his struggle to embody these new signs. “I ceased not to preach that it was our privilege to receive the Holy Ghost and speak in tongues as they did on the day of Pentecost. I did not have the experience, so I was almost always among the altar seekers.” 30 The pursuit of baptism consumed him, as he “was so hungry for the Holy Ghost that I scarcely cared for food, friendship or anything else.” 31 He was rewarded with an intense experience. He claimed that he levitated, shook, and fell to the floor. He spoke in “ten different languages,” miraculously traveled to numerous countries, and saw a vision of some great, bloody future conflict. Following this experience, Tomlinson made signs and miracles a key feature of his rapidly growing movement.

Before trading the Unicoi Mountains for the nearby city of Cleveland, Tennessee, in 1905, most of Tomlinson’s followers resided in distant mountain communities in the rural areas of “Monroe, Polk, Bradley, and McMinn counties in East Tennessee and Cherokee County in Western North Carolina.” 32 According to historian Mickey Crews, early church members “tended to live outside the social and economic mainstream. Just as Appalachia was on the periphery of the South, they too lived on the fringe of the dominant society.” 33 The church’s earliest preachers and converts tended to be poor, rural whites with little education and few means. 34 Many were critical of the industrialization of Appalachia and skeptical of the middle-class values associated with urban life.

The manifestation of signs not only created distinctions between pentecostals and non-pentecostals, but also between competing pentecostal groups. From the earliest days of Parham’s Topeka outpouring of the Latter Rain to Seymour’s Azusa Street revival, pentecostals exhibited a broad consensus that the manifestation of “tongues” indicated one’s baptism by the Holy Spirit. Yet, within this wide consensus, individual signs could be interpreted narrowly or broadly, therefore creating boundaries between groups and reinforcing hierarchies within various groups. For instance, as religious studies scholar Ann Taves has noted, Parham and Seymour disagreed over which tongues counted as true signs of Holy Spirit baptism. Taves noted, “Parham believed that the authentic ‘bible evidence’ was always in a human language unknown to the speaker.” 35 In contrast, Seymour “viewed a much wider range of experiences as authentic.” 36 The struggle to define these symbolic differences and efforts to control the circulation of these signs (and the bodies that manifested them) led to shifting allegiances and conflicts within early pentecostalism.

For southern pentecostals, such as those affiliated with Tomlinson’s Church of God, controversies over the nature and meaning of signs became a significant aspect of the new movement’s development. Tomlinson was especially concerned with signs, and dedicated a large amount of his prolific writing to the subject. He saw signs as an essential component of Christian history and made them a cornerstone of his growing church. “Signs,” he wrote, “are made prominent in the Bible from the beginning to end. God gave Noah the sign of the bow in the sky. He gave Abraham the sign of circumcision. The signs God gave to Moses to convince the people of the power of God…. The New Testament signs will continue until the Lord’s people are finally delivered.” 37 Signs, therefore, not only helped establish one’s position within the Church of God, but they also bestowed a sense of spiritual power to many of the Church of God’s otherwise economically and socially impoverished members. Tomlinson enthusiastically embraced Cashwell’s holiness synthesis and aggressively popularized a pentecostal theology because the tongues of Acts and the signs of Mark formed a reservoir of spiritual and social power for the members of the rapidly growing Church of God. The collective pursuit of signs distinguished Tomlinson’s followers from their rapidly changing surroundings. Signs separated them from the market and industrial forces reshaping Appalachia and highlighted their divergence from the long-established religious bodies in the region.

Tomlinson’s followers translated his emphasis on the disciplined cultivation of embodied signs into the popular idiom of modern advertising. One Church of God member from Chattanooga told readers of the widely circulated Church of God Evangel that, just as “we walk down the street and see signs in front of the store, and we expect to find what they are advertising,” Christians too “are living signboards” who can be identified by outward manifestations of their inner faith. 38 Signs such as “speaking in tongues and taking up serpents” function as advertisements broadcasting either godliness or sinfulness. 39 “There are many wrong signs. Confusion is not a sign of godliness…. Then if you have the sign of confusion up, take it down…. The world is reading your sign.” 40 If one is to be read as Christian, the author argued, one must accumulate and display the full range of Markan signs—“taking up serpents” included—as an index of a distinct Christian life.

So what happened? How did taking up serpents, a practice once casually and unproblematically mentioned on the same symbolic level as speaking in tongues, transition from being a “sign of godliness” to one of “confusion” in the minds of many southern pentecostals associated with the Church of God? How and why did serpent handling cease being one of the acceptable Markan signs? How did it become a dangerous practice not befitting respectable pentecostals? To answer these questions, one must trace the ways in which members of the church developed mechanisms for evaluating embodied signs, regulating their practice, and determining their relative value within their respective social structures. This evaluative process emerged from engagement with popular media sources (especially newspaper reporting) and secular authorities. Members of the Church of God and other churches worked to build a community of believers simultaneously set apart from the dangerous and corrupting influences of mainstream culture and distinct from the extreme fractiousness of those who insisted that Jesus commanded the handling of poisonous snakes.

Signs and Miracles

Historian Randall Stephens has noted that holiness newspapers provided a crucial medium for spreading the pentecostal revival throughout the South. “The immediacy of newspapers,” Stephens has argued, “and the ways in which they allowed individuals throughout the U. S. to correspond with one another made them an unusually potent medium.” 41 Following Benedict Anderson, Stephens noted how the mass production of cheap newspapers helped “the emerging pentecostal community” foster an imagined sense of homogeneity and simultaneity across space and time. 42 These journals questioned the sufficiency of other modes of religiosity to express a fully sanctified Christian life, and, most importantly for this essay, helped create a common system for interpreting manifestations of Holy Spirit baptism.

Even as these publications provided an important mechanism for forging a collective, imagined identity for the growing pentecostal churches of the South, they also recorded debates over how this emerging community would and could imagine its limits. Within these debates, popular journals helped establish which signs would freely circulate as embodied expressions of Spirit baptism. For example, Stephens pointed out that as older southern holiness advocates clashed with the pentecostal newcomers, these publications recorded conflicts “between non-tongues speaking holiness people and pentecostals” as they battled over claims of “authentic” and “complete” experiences of God’s sanctifying grace. 43

Not surprisingly, as word of serpent handling spread in the holiness-pentecostal press, the controversial practice also became a contested sign of Holy Spirit baptism. These sources recorded the early history and diffusion of serpent handling in Appalachia while also illuminating the complex processes of symbolic differentiation that eventually influenced popular, non-pentecostal understandings of this controversial sign. Although many publications associated with southern pentecostalism commented on serpent handling, few lavished it with more attention—and praise—than The Church of God Evangel, the official publication of the Church of God (Cleveland). Edited and published by Tomlinson, Evangel appeared in 1910 and grew apace with the church. By 1914 Evangel was a weekly, newspaper-format publication and at the end of the decade it claimed more than 15,000 subscribers. 44

On September 12, 1914, an anonymous note appeared in Evangel: “Bro. George Hensley is conducting a revival at the tabernacle in Cleveland, Tenn. It began the last Saturday in Aug. and is still continuing with increasing interest. The power has been falling and souls crying out to God. Twice during the meeting Serpents have been handled by the Saints.” 45 Reports of the revival soon found their way into a series of secular newspapers making George Went Hensley a regional celebrity. 46 The few existing sources make it difficult to discern Hensley’s motivation for taking up serpents, but it is easier to understand why Hensley’s innovation eventually received considerable attention from early leaders in the southern pentecostal movement. 47 Hensley commenced his revival just as a generation of church leaders began defining the nature and meaning of “signs” associated with baptism by the Holy Spirit.

Scholars have long speculated that snake handling—as both a religious ritual and a folk practice—predated Hensley by perhaps a decade, but apparently religious leaders did not feel a need to record earlier incidents of snake handling at coal camps or in brush arbor meetings. 48 The earliest references to serpent handling appeared in non-southern sources. 49 Secular news sources from 1909 reported on a “queer sect” of “snake worshippers” in Hutchinson, Kansas, that allowed snakes to bite one another during worship services. 50 These accounts did not frame the worshippers as holy rollers and did not regard them as pentecostal even though the handlers quoted in these reports directly appealed to a pentecostal logic for handling snakes and specifically cited the “signs” of Mark 16. 51 For their part, the “snake worshippers” self-identified as the “True Followers of Jesus of Christ.” As with Hensley’s later embrace of the practice, these earliest accounts suggest that a certain convergence of reading, healing, and preaching strategies connected to Mark 16—in conjunction with attention from the popular press—led to the development of the practice in the early twentieth century. The Hutchinson church attracted attention because it allowed children to handle snakes and at least one church member had gone “missing” (likely died, but the sources are not clear on this issue) as a result of handling snakes in church.

By the 1910s, however, as more and more pentecostals throughout the South debated Holy Spirit baptism, secular and religious media alike appropriated this new practice into the holy roller phenomenon. If in the 1909 accounts of serpent handling reporters failed to connect the practice to holy rollers, by 1913 reports in Texas and Georgia newspapers did make the connection. These stories recounted events in northeastern Alabama and specifically related them to a series of “Holy Roller” revivals near Sand Mountain. One story described children handling snakes. 52 Two others told of a Rev. James Halsop’s death following a series of snakebites as he tried to pull a rattlesnake from a bag. Halsop’s death appears to be the first recorded that is clearly attributable to serpent handling. 53

Despite this earlier spotty evidence of several groups taking up serpents as a result of their contact with holiness-pentecostal theology, the sensation caused by Hensley’s 1914 revival has become synonymous with the origin of serpent handling. 54 In many ways, Hensley embodied the target demographic of the early Church of God. Before he began handling snakes, Hensley was an illiterate moonshiner with no permanent residence who supplemented his ill-gotten income by working variously as a miner, a lumberjack, and as a factory worker. Like many other early Church of God members, Hensley had roots in rural mountain communities in West Virginia and Tennessee. 55 Many of these communities were more-or-less homogeneous, made up mostly of poor whites from the same economic and educational strata of society. They worked in coal mines, as day laborers, semi-skilled factory laborers, or rural subsistence farmers. Initially, in the early 1900s, the Church of God preached almost exclusively to these communities in Appalachia. Indeed, as some scholars have noted, there seems to be a complex relationship between industrialization, greater mobility, social change, and the explosion of the holy roller revival in the South. 56 These changing patterns of communication and transportation brought men like Hensley into contact with the Church of God and became the primary channels for spreading serpent handling.

Given Hensley’s apparent appeal to this target audience, it is hardly surprising that a week following the initial report of the revival, Tomlinson’s lead Evangel article, “Sensational Demonstrations,” discussed the sign of serpent handling at length. 57 Tomlinson reported that he was told, “the saints had been handling snakes and that it was creating quite a sensation.” 58 The more Tomlinson asked about the revival, the more interesting the story became. First, Hensley had preached on all of the signs listed in Mark 16:18. Next he prophesied that some rabble-rouser would bring a snake for the saints to handle. The following night an unbeliever brought a rattlesnake which several saints handled “and no one was injured by it. Some were bitten, but with no damage to them.” 59 After this successful sign, “outsiders got enthused and wanted to test the matter further. So on Sunday night Sept. sixth they took in a ‘Copperhead.’” 60 The saints successfully handled this snake too. News of these demonstrations generated “large audiences.” 61

Had Tomlinson’s engagement with serpent handling ended with a single article, it is likely Hensley’s revival would have been as easily forgotten as the Hutchinson and Sand Mountain churches. Instead, Tomlinson continued to write about the practice and used it in his outreach to the local media. Tomlinson’s reason for embracing serpent handling grew from the competition between various pentecostal groups hoping to legitimize the relative intensity of their respective Holy Spirit baptisms through the manifestation of signs. “A letter from some uniformed personality,” Tomlinson reported to readers, “found its way to my desk recently which stated that the Church of God people were far in the rear in regard to manifestations of the presence and power of God and the salvation of souls. It stated that God was evidencing His approval of other ‘apostolic movements’ far more than the Church of God.” 62 To concede that the Church of God had fallen behind in the manifestation of signs would have been an admission of the church’s deficit of symbolic capital. Not to be outdone, Tomlinson emphasized that the church had manifested basic signs such as glossolalia and divine healing. Then he upped the symbolic ante. “During the past year,” wrote Tomlinson, “new experiences have materialized. In several instances, as has been noted in the paper, fire has been handled by several parties.” 63 Along with fire handling, Tomlinson also noted, “the saints had been handling poison snakes.” 64 Later in 1914, Tomlinson doubled-down on serpent handling at the Church of God’s Tenth General Assembly in Cleveland, telling the church’s leaders, “Wild poison serpents have been taken up and handled and fondled over almost like babies with no harm to the saints. In several instances fire has been handled with bare hands without the saints being burned. … I Have seen no reports of anybody outside the Church of God performing this miracle.” 65

The following year, Tomlinson elevated serpent handling up the semeiotic hierarchy above the more commonly practiced signs. “The past year,” wrote Tomlinson, “has been one of progress which has led us into many miraculous things. Quite a number have been able under the power of God to take up serpents and thus demonstrate the power of God to a gainsaying world.” 66 With the emphasis on “progress,” Tomlinson indicated that handling emerged out of lower signs such as divine healing and speaking in tongues. Later in a 1917 speech before the Thirteenth General Assembly, Tomlinson reiterated the Church’s support for the practice. “The Church of God,” he insisted, “stands uncompromisingly for the signs and miracles, and upholds the taking up of serpents and handling fire under the proper conditions.” 67

From 1914 to 1920, Tomlinson authored no less than eighteen lead Evangel articles touting the sign of serpent handling. 68 In the same period, he also published at least 53 reports of serpent handling authored by revival leaders, preachers, and laypeople. 69 These short revival testimonies and conversion accounts, written in bursts of evangelical fervor from the frontline of the “battlefield for God,” tell of revival meetings full of all manner of miraculous signs. 70 A representative dispatch recounted: “Hot lamp chimneys were handled and some handled the hot torch without hurt. Large snakes were brought in… and were successfully handled.” 71 Reports rendered graphic tales of severe snakebites, swollen limbs, and vomiting saints in the matter-of-fact tone of spiritual utility: God allowed snake bites to demonstrate God’s control over the situation. 72 Militaristic metaphors of “battle” against Satan and “victory” over sin framed the way the authors imagined their evangelistic efforts. 73

While most accounts concealed the sources of the snakes in the passive voice—“there was a rattlesnake brought in”—some reports do indicate that outsiders brought the snakes to challenge the congregations. 74 For his part, Tomlinson believed that these sorts of challenges and the saints’ willingness to meet them had “been a great factor in stopping the mouths of gainsayers, and convincing unbelievers of the power of God.” 75 In an account of one such confrontation, a group of skeptics brought a “rattle snake pilot” to a meeting and challenged the saints to handle it. 76 In an act of marketing savvy, the group scheduled to handle the snake the next day at two in the afternoon. Word of the event spread and the “country was stirred for miles and a large crowd came.” 77 The group preached for two hours on the “Signs of God,” then four members of the Church of God handled the snake. According to the account, “The Lord allowed him the snake to bite two of the sisters. This was to show the healing power of the Lord.” 78 Some accounts claimed hundreds of witnesses to similar events and many indicated that some observers converted after seeing snakes handled. 79

Even though these reports in Evangel suggest that only a tiny minority of the Church of God ever handled snakes in their meetings, the frequency of their publication (sometimes two or three accounts of handling appeared in a single issue) indicates an interest on the parts of both Tomlinson and his readers. The rhetorical consistency of the reports suggests that their authors and many of the thousands of subscribers to Evangel believed that the sign of handling not only attested to the basic validity of their Spirit baptism experiences, but that it was also an important aspect of their spiritual symbolic order. The handling of dangerous snakes reinforced the Church of God’s imagined status as some of the most sanctified and blessed people on earth. Tomlinson often made this claim. In one particularly pointed response to a critic of the church’s position on signs, Tomlinson chided, “I suppose this gentleman is angry because God is so wonderfully blessing our people and confirming the Word by so many signs. I suppose he the critic is not able to do such things as we are doing, such as taking up serpents, handling fire, casting out devils, and healing the sick, all by the power of God.” 80 Failure to handle poisonous snakes or fire was akin to the failure to manifest other signs such as speaking in tongues. This failure suggested a real spiritual deficiency, while the presence of serpent handling in the Church of God symbolized its holiness.

As the 1910s drew to a close, Tomlinson and many others believed that members of the Church of God could successfully manifest the most dangerous signs in the symbolic hierarchy of Holy Spirit baptism. This emphasis on dangerous signs coincided with a period of rapid expansion of church membership. From 1914 to 1922 the Church of God more than tripled in size to nearly 20,000 members and the circulation of Evangel surged to 16,000 by 1916. 81 Reports of Hensley’s 1914 revival in regional newspapers had heightened the public’s awareness of the church and linked its growth to the handling of poisonous snakes. The combined weight of church growth and frequent press coverage of serpent handling points to a general willingness on the part of Tomlinson and other Church of God leaders to adopt controversial signs in order to gain symbolic leverage over their religious and secular adversaries. Further, Evangel’s frequent coverage of handling indicates that the practice was important to how the publication’s community of readers imagined their status as saints. Within this imagined community, serpent handlers were not a distinct or separate group of worshippers. Those who took up snakes were identified as saints, brothers, and sisters. Each title testified to their acceptance within the wider Church of God polity. The saints of the Church of God distinguished themselves from members of other denominations who failed to manifest the progressive expressions of Holy Spirit baptism represented by all of the Markan signs, including serpent handling.

Before turning to non-Church of God responses to the practice, it is worth reiterating that the practice of serpent handling did not originate with Tomlinson and its continuation was not contingent on his approval. The practice predated its appropriation by the Church of God, emerging more or less simultaneously in Kansas, the Ozarks, the Sand Mountain region of Alabama, and in Tennessee around the cities of Chattanooga and Cleveland. Many of these incidents—recorded in local newspapers, Evangel, and enshrined in popular memory—happened in proximity to the early activities of the Church of God but were not directed by it. The Church of God, under Tomlinson’s leadership, attempted to ride the whirlwind of serpent handling by providing a retrospective legitimation for an independently emerging practice. The church appropriated the practice to cultivate its members’ sense of distinctiveness and to attack its religious and secular adversaries. Other denominations perceived this challenge and immediately condemned the practice in their official publications even, as outlined in the next section, some of their readers exhibited a sustained interest in the validity of the sign and pushed back against their hierarchies’ rejections of the sign.

II. Signs and Serpents in the Holiness-Pentecostal Press

In the early 1920s, Tomlinson lost control of the ecclesiastical structure of the Church of God. A revolt in 1923 over fiscal issues and ecclesiastical power forced Tomlinson from his position as General Overseer of the church and led to the creation of two competing groups both vying for the title of “Church of God.” While Tomlinson continued to advocate for serpent handling as a legitimate sign, he did so from the weaker position as the Overseer of the much-diminished Church of God of Prophecy. 82 The departure of Tomlinson and his loyalists led to a rapid reassessment of the sign of serpent handling within the body of the Church of God (Cleveland). There had long been quiet rumblings of discomfort regarding Tomlinson’s support for the sign, and now the remaining leaders moved to rethink and ultimately reject the practice. In this process, the Church of God adopted a position that mirrored other pentecostal denominations’ rejection of willful or active snake handling. As a result, snake handling developed into a distinct practice of a small, ostracized minority at the edge of the Church of God’s polity. This repudiation of the practice led to the creation of a hard boundary in the Church of God between the saints and a new class of spiritual outlaws who persisted in the eccentric practice of snake handling.

Serpents as Signs

Despite Tomlinson’s insistence that the Church of God was unique in its embrace of serpent handling, material published by other early pentecostal denominations indicates that he was hardly alone in explicating the symbolic importance of “taking up serpents.” Myriad non-Church of God publications from the early 1900s attest to the symbolic implications of the serpent for the growing pentecostal movement. Many stories published during this period discussed the serpent as a tempter that sowed discord among pentecostals. 83 Other stories were especially concerned with explaining the Christological implications of Moses’s brazen serpent and its relationship to Mark 16 as harbingers of Jesus’s Great Commission. 84 Had such symbolic interpretations ended there, then one might rightly conclude that Tomlinson’s literal reading of the Markan signs was an idiosyncratic and ephemeral project of the early Church of God. Yet, during the first decade of the pentecostal revival, reports flowed into non-Church of God newspapers and magazines recounting the miraculous manifestations of the Holy Spirit as they related to the handling of poisonous snakes. Nowhere was this clearer than in the network of publications associated with the Assemblies of God.

From the 1910s to the early 1920s, the vast majority of these reports were especially interested in Mark 16:18—”they shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover”—because of its relationship to various missionary activities abroad. Many of the early reports collected in the Chicago-based Stone Church’s The Latter Rain Evangel told of missionaries in India, China, and Africa. These tales resounded with praise for God’s protective power against poisonous serpents in the missionary field. Led by William Hamner Piper, Stone Church, as historian R. G. Robins has noted, “quickly emerged as a force for missionary outreach and publication of the young pentecostal movement. Its presses churned out volumes of tracts, books, and pamphlets, along with The Latter Rain Evangel.” 85 Stone Church hosted the second general meeting of the Assemblies of God in 1914 and its publications had a major impact on the early theological development of a host of pentecostal denominations. Within this context, the Stone Church helped influence a generation of early pentecostals with reports of missionaries threatened by snakes and poison. For example, one representative report from 1913 linked Mark, serpents, and foreign missions: “Our faith is quickened as we read of the remarkable providences and deliverances in the lives of missionaries; how God closed the mouth of the wild beast, took the poison from the serpent’s bite, and manifested Himself in innumerable ways as the Deliverer of those who were faithful to His last commission.” 86 Thus, The Latter Rain Evangel set an early precedent encouraging missionaries and average readers alike to associate the Holy Spirit baptism with power over poisonous snakes. 87 This would have consequences for the Assemblies of God as readers of its publications would connect miraculous missionary work abroad with spiritual warfare in revivals at home.

Beyond references to missionary work in exotic lands, some Assemblies of God publications also contained accounts of worshippers at revival meetings in the United States who were accidentally struck by snakes. These testimonies are relevant because they highlight the similarities and differences between the Assemblies of God’s emerging understanding of “taking up serpents” and the Church of God’s alternative interpretation of the practice. In the Assemblies of God, serpent bites were more often than not directly associated with the healing power of the Holy Spirit indicated in Mark 16: 17-18. 88 For example, in a notable case at a prayer meeting in Dayville, Oregon, a rattlesnake struck Ralph C. Burnett who had recently received the gift of the Holy Spirit. Immediately following the bite, “Brother and Sister Walter Morris who lived nearby… anointed me with oil, and prayed for me according to Mark 16:17, 18. The healing virtue of the Lord Jesus went through my body like an electric current and I was instantly healed…. My companion, Brother Stockton, and I were singing, ‘These Signs Shall Follow Them That Believe,’ when without any warning the rattler struck me.” 89

While Burnett sought healing through prayer and laying on of hands, at least a few others prayed for the danger associated with snakebites in order to witness for God’s power. In a case similar to many recounted in Tomlinson’s Church of God Evangel, Alice Hannah of Prescott, Arkansas, was accidentally struck by a snake. As her fellow churchgoers anointed her with oil and prayed for healing, Hannah prayed her own prayer: “I told the Lord to leave any sign He wanted, that others might know He could heal the bite of a poisonous snake; so He let my foot swell. I was bitten on Monday and never put my shoe on that foot for five days, yet never failed to play the organ and help in every service.” 90 Her prayer implied not only familiarity with Mark 16:18, but also a selfless willingness to accept the risks of a severe snakebite. Similarly, Lucy A. Luttrull of Bruner, Missouri, reported being bitten by a copperhead while speaking in tongues. She refused medical treatment and allowed a brother and sister to anoint her with oil and pray over her. 91 As with Hannah’s prayer, Luttrull willfully accepted the risk associated with the bite as a sign following from her belief. 92

The slipperiness between the incidental handling of dangerous serpents and the willful courting of suffering to prove the sufferer’s status as one of “them that believe” seems to have necessitated a series of statements from early leaders in the Assemblies of God. Unlike the Church of God’s theology that handling emerged as a progressive sign of the power of the Holy Spirit, leaders in the Assemblies of God instead emphasized that Mark 16:18 served as a general “promise of protection in the face of every believer” who might encounter a deadly serpent. 93 Significantly, the Assemblies of God’s unambiguous insistence that the Markan signs promised limited protection against accidental contact with serpents and poisons did not end questions from church members regarding the sign of serpent handling. On no less than four occasions between 1915 and 1922, E. N. Bell, the First General Chairmen of the Assemblies of God, felt it necessary to respond directly to questions about the practice of serpent handing in his regular columns. He insisted on protection against the “incidental” handling of snakes but rejected anything else as “tempting God.” 94 In the late 1910s and early 1920s, Bell condemned serpent handling, but was less explicit in condemning the handlers themselves. It is instructive to note that this question arose repeatedly during the period when the Church of God advocated for the sign throughout the South. Explicit condemnation of serpent handlers as evil agents of Satan became more common in the 1920s as the Church of God revised its position on handling serpents—a revision that allowed other groups to condemn not only the practice, but also its practitioners.

“Beware the Church of God”

Even with the Church of God’s initial support for Hensley’s sign, there were skeptics in the body of the church who fretted over serpent handling’s divine validity. Their concerns echoed the consensus emerging in the publications associated with of the Assemblies of God. Long before Tomlinson was forced to relinquish control over the Church of God in 1923, two early dissenters raised concerns about the practice. First, in 1914 shortly before Hensley held his Cleveland revival, J. B. Ellis, an important minister of the church, offered a stern warning to handlers: “I would like to say a few words to the saints who handle fire and serpents. These things come under the head of miracles, and Paul says ‘All do not work miracles’…. Only the mercy of God has kept some of them saints who take up serpent out of the grave. God has given them several object lessons that ought to teach them there is a limit to it.” 95 Ellis concluded that handling was a miracle, but he presented it as an individualistic pursuit that did not strengthen the collective body of the church. Instead of focusing on handling serpents, Ellis urged members to use the signs of Spirit baptism in a “more excellent way.” If the saints would “command the lame to walk, the blind to see, and the deaf to hear” then “they would use their gifts to profit withal.” 96 Next, in a 1919 Evangel article M. S. Lemons authored a convoluted report that suggested serpent handling is sometimes “A Misappropriation of His God’s Power.” 97 On one level, Lemons argued that it is impossible for “weak men” to misappropriate the power of the Holy Spirit “for illegal purposes,” therefore implying that handling serpents is legitimate. 98 On another level, however, Lemons worried that believers had “got the cart before the horse” and instead of letting the signs follow from grace, believers were attempting to “follow the signs” by taking up snakes. 99 In such cases, he warned, God “will let them the snakes take your life.” 100 He ultimately concluded, “If this work is of man it will come to naught.” 101

After Tomlinson’s forced departure in 1923, critics of handling started to condemn the practice. This condemnation emerged as the Church of God’s leaders sought cooperation rather than competition with other pentecostal groups. The Church of God’s need to distance itself from the practice was partly a function of Tomlinson’s early success at making serpent handling a divisive issue in other pentecostal denominations. Groups ranging from the Pentecostal Holiness Church to the Pentecostal Mission to the Assemblies of God warned against the practice. Of these groups, the first to offer a straightforward rejection appears to have been the Pentecostal Holiness Church, which condemned snake handling in 1917. 102 Anthropologist Steven M. Kane has argued that the Pentecostal Holiness Church told its members to “Beware the Church of God” because serpent handling was attracting converts to the Church of God and interrupting Pentecostal Holiness Church meetings. 103

Unlike the Pentecostal Holiness Church, the Pentecostal Mission warned against handling but, because of connections to the Church of God, initially stopped short of condemning serpent handlers. Hattie M. Barth, an early leader of the Atlanta-based organization, wrote in 1919 in the Bridegroom’s Messenger, “Two of these signs of God’s Word, which are at present attracting much attention, are the handling of serpents and the handling of fire. These displays of supernatural power attract crowds to the services, and some are favorably impressed with these things, while to others they are stumbling-blocks.” 104 After carefully considering these signs, Barth concluded that handling serpents is acceptable if it is accidental, as in the example of the Apostle Paul being struck by a snake while collecting wood. 105 However, in the cases of willingly handling fire or poisonous snakes, she dismissed such actions as “misdirected power.” Echoing J. B. Ellis, she concluded, “We understand that in these very assemblies where there is handling of serpents and fire, the lame come away unhealed, the blind eyes are not opened, nor the deaf ears unstopped.” 106

While competition with the Church of God had prompted the Pentecostal Holiness Church to condemn serpent handling, institutional connections between the Pentecostal Mission and the Church of God forced Barth to refine and clarify her position two months later. In a conciliatory note, she responded to “several of the saints” who attacked her original article on the subject. While she remained convinced of the danger of these signs, she conceded that she had not witnessed them firsthand and therefore did not “oppose the rightful use of these signs, but the abuse of them.” 107 Ultimately, her response suggests that the real issue was not the handling of serpents and fire per se, but rather the notion that these signs might attest to some sort of spiritual superiority on the part of handlers: “they the handlers also claim greater power than other Pentecostal people because of this handling of serpents and fire, although it does not seem, from what we can learn, that they have greater power along other lines, such as healing the sick.” 108 Barth’s argument pushed back against Tomlinson’s insistence on the progressive spiritual superiority of the Church of God. With this concern in mind, it is worth emphasizing that, in the end, Barth referred to supporters of handling as “friends” and “saints.”

Although Barth had to admit that she had not personally witnessed handling, some in the Assemblies of God did have direct contact with the practice. This is likely because of the overlapping territory of the Assemblies with the Church of God. Initially organized in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1914 as an umbrella organization combining more than one hundred pentecostal congregations throughout the South and Midwest, the Assemblies of God became one of the largest and most dynamic of the early pentecostal denominations. As the memberships and geographic boundaries of the Assemblies of God and the Church of God exploded in the late 1910s, the two groups often found themselves in contact with one another and competing for converts.

In September 1917, Jethro Walthall reported on his contact with the Church of God. While proselytizing in rural Arkansas, Walthall reported on a small congregation in Marysville:

From thence we went to Marysville, Ark., where we found the little assembly confused, a number of young people having backslidden, and others discouraged. A man of the Church of God plea was in the community and had taken advantage of the conditions to install his second cleansing, snake handling theories. We allowed him liberty in the meetings until we saw he was determined to use every opportunity, in testimony and otherwise, to get his tenants before the people. When we saw that he would not work in harmony with the spirit of the meeting …e had to forbid him, who then went from us crying persecution. We never rallied over the confusion and hence the meetings were a failure, except that the Saints were helped and established. 109

Walthall’s account illustrates three important facts related to serpent handling in both churches. First, on a popular level, serpent handling was nearly synonymous with the Church of God; Walthall, and likely many others in the Assemblies of God, understood the two to be inseparable. Second, when one considers Walthall’s anecdotal evidence within the contemporary context—which included the pushback against Barth’s condemnation of the practice, the institutional competition between various pentecostal groups, members of the Assemblies of God courting snake bites, numerous letters published in Evangel recounting the draw of the practice in revival meetings, and a host of stories and letters to the editor published in non-religious newspapers—it seems likely that the practice was having an influence beyond the Church of God and leading to conflict in some revival meetings and rural churches. The Church of God representative in this account used his “theories” to highjack a congregation that Walthall believed should be closer to the Assemblies of God’s interpretation of signs. Walthall deemed this novel interpretation dangerous and believed it contributed to confusion within the church. Third, even though he clearly rejected the practice of handling, Walthall was reluctant to aggressively condemn the handler and instead initially allowed the Church of God supporter “liberty” to speak on the issue. As with Barth’s hesitance to reject the handlers, Walthall’s account suggests that serpent handling retained enough of a miraculous aura that outright condemnation might have alienated many in his target audience. This hesitancy to condemn the handlers diminished as the Church of God ceased to use serpent handling as cudgel to bludgeon its opponents.

Rank Fanaticism

Under the leadership of Flavius Josephus (F. J.) Lee (1875–1928), the Church of God’s second General Overseer, the church moved to undermine its association with the practice of serpent handling. As historian Mickey Crews has noted, Lee considered merging with the Assemblies of God and as a result downplayed the practice. 110 In 1928, at the church’s Twenty-Third General Assembly, leaders refused to make handling a test for fellowship, although the assembly did not officially ban the practice. 111 Shortly before the Twenty-Third General Assembly’s clarification regarding handling, S. J. Heath published an article in Evangel that indicated a clear transition in the church’s collective interpretation of the sign. He took exception with serpent handlers because they were “using the Church of God as a medium to advertise snake shows.” 112 This, wrote Heath, “is absurd and ridiculous” because “many have gone into rank fanaticism, and false teaching, bringing reproach on the Church of God, and disgust to intelligent people.” 113 The evocation of advertising alluded to the established theme that the body is a signboard for various Godly or un-Godly messages. If Ellis and Lemons had earlier paid lip service to the legitimacy of the sign, Heath, in contrast, now openly condemned snake handling. In the end, all three critics sought to change the entire symbolic framework for understanding the sign by shifting it from the religious to the secular realm. In this way, they read pride, showmanship, and illegality written on the bodies of snake handlers. This symbolic shift marked the beginning of the end of the practice’s association with the Church of God.

The new focus on pride and showmanship brought the Church of God in line with other major denominations such as the Assemblies of God. If, as outlined in the previous section, the Assemblies rejected the practice in the 1910s but hesitated to condemn the handlers themselves, then by the mid-1920s the body, perhaps freed by the Church of God’s moderation on the issue, had changed course. Ernest S. Williams—who would eventually serve as the Fifth General Superintendent of the General Council of the Assemblies of God—called the practice Satanic. “What shall we think of those who for vain show would presume to take up serpents, and otherwise tempt the Lord our God? Shall we consider them superior in spirituality? Nay, but rather they are drawn away of Satan being enticed to presume on gospel favors.” 114 By the end of the decade, condemnation had given way to a general insistence that taking up snakes or drinking poison are merely “passive signs” needing no sophisticated interpretation. 115 Those who insisted on such interpretations were—consciously or unconsciously—agents of Satan.

As the 1920s closed, only a tiny handful of stories in the Church of God’s Evangel favorably mentioned revival activities including serpent handling. By 1936 the few remaining positive references were replaced by harsh condemnation. 116 In 1939, E. L. Simmons, the editor and publisher of Evangel, dismissed “modern ‘snake handling’” as feeding “upon a spirit of showmanship.” 117 His invocation of the category of the “modern ‘snake handling’ movement” marked a culmination of two decade’s worth of rethinking of the sign of serpent handling on the part of the Church of God’s leadership. As snake replaced serpent in the church’s symbolic framework, the practice no longer possessed any lingering spiritual aura and, consequently, demanded neither the respect nor the support of the church. To handle a snake is to manipulate a mere animal, not a serpent, humanity’s great spiritual adversary. Further, the suggestion that the spirit of snake handling is showmanship displaces the Holy Spirit from the practice. Suddenly, “modern ‘snake handling’” was little more than a carnivalesque aberration whose practitioners misappropriate Scripture for un-Christian purposes.

III. Serpent Handling in the Secular Press

The shift from serpent to snake within the Church of God not only marked a transition toward denominational cooperation, but also coincided with intensified secular media coverage of the practice. Church leaders came to regard the once-perceived evangelistic benefits of the practice as liabilities. As the Church of God withdrew support for the practice, municipalities and states passed laws banning it. Appalachian states began banning the handling of snakes in public venues in the 1940s. Kentucky went first in 1940 by explicitly banning the use of “any kind of reptile in connection with any religious service.” 118 Most other Appalachian states followed (with the exception of West Virginia), but none adopted Kentucky’s broad approach. For example, Georgia (1941) and North Carolina (1949) banned exposing people to poisonous snakes and also made it illegal to encourage someone to handle a poisonous snake—a prevision aimed at ministers who preached on the subject.

These state laws had the combined effect of focusing the public’s attention on the specific act of picking up a snake in a public venue. Nowhere was this focus on the act of displaying a snake in public clearer than in the media frenzy surrounding the run up to and the aftermath of Tennessee’s ban of the practice in 1947. A series of highly-publicized deaths and conflicts between serpent handlers and police prompted the state to do something about the practice. 119 Tennessee determined, “It shall not be lawful for any person, or persons to display, exhibit, handle or use any poisonous or dangerous snake or reptile in such a manner as to endanger the life or health of any person.” 120 The Tennessee law prompted the arrest of Hensley and other handlers and led to a trial and national media coverage.

George Went Hensley preaching near the Hamilton County Court House in Chattanooga,Tennessee, in 1947. Photograph by J. B. Collins. Courtesy of Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University, J.B. Collins Collection.

Following Tennessee’s 1947 ban on serpent handling, officials in Hamilton County arrested twelve members of the independent Dolley Pond Church of God with Signs Following, including its head preacher Tom Harden and Hensley. The case ended in convictions and \$50 fines for the handlers, both of which the Tennessee State Supreme Court later upheld. The media spectacle turned Hensley and the other handlers regional celebrities and aroused national interest in the “strange religious cult” of the “snake handlers of Tennessee.”

In the years leading up to Tennessee’s ban and the decade’s worth of coverage of the enforcement of the law, readers of regional newspapers, national outlets such as Newsweek, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Time, and any number of popular books learned of snake handling in Appalachia. 121 But this recognition of snake handling was hardly spontaneous. Just as it took holiness-pentecostals nearly three decades to reach the consensus that snake handling was a distinct practice at odds with mainstream forms of pentecostal worship, similarly it took decades for the secular press to identify snake handling as something unique from holy roller religion. This process of differentiation moved through three distinct but mutually reinforcing phases. First, initial reports of the practice in the secular press conflated snake handling with not only the Church of God but also holy rollers more generally. Next, as reporting on the practice increased, stories focused on the dangers of taking up snakes and sought to explain the seemingly pathologically irrational behavior of handlers with various psychological and sociological theories. It is in this era that the secular press identified the distinct practice of snake handling. Finally, by the late 1940s, reporting and editorials focused on the criminalization of the unique practice identified during the previous decade. The development of the pathologized and criminalized category of snake handling paralleled the decline in usage of pejorative categories, such as holy rollers, by the press and the growing normalization and wider cultural acceptance of pentecostalism.

From Holy Rollers and Cultists…

The earliest coverage of snake handling in the secular southern press tended to focus on the absurdity of the practice by mocking the leaders of the various revivals in which believers handled snakes. For example, in a series of articles published in and around Chattanooga and Cleveland documenting George Went Hensley’s 1914 Tennessee revival, reporters noted the dangerousness of the practice, but chose to use handling as a vehicle for ridiculing holy rollers—that is, pentecostals in general. 122 In these early stories, reporters most commonly referred to the handlers as holy rollers or members of the Church of God. The reporters imposed the former title on the handlers, while the handlers self-identified with the latter title. Even though the Church of God despised the epithet holy roller, the conflation of terms in the minds of the reporters and, eventually, their readers was not accidental. 123 One story reported that the Church of God office in Cleveland actively promoted serpent handling as part of its public outreach:

There are evidences that the leaders of the Holy Rollers in this vicinity are conducting a thorough campaign to win strength of a financial and material sort to their organization. In a little house in the northern part of Cleveland one man, one woman and two girls are kept busy setting type. Between takes they invite you to church, explaining that, perhaps, as a special inducement, there’ll be a rattlesnake to give tone to the meeting. 124

No doubt the typesetters identified here played an important role in publishing many of the accounts of serpent handling that appeared in Evangel in the 1910s.

From the late 1920s to the early 1940s, most reports abandoned labels such as holy rollers or Church of God to identify serpent handling saints. 125 The new titles that dominated the coverage during this period included cult (or cultists), believers, religionists, and fanatics. At the national level, the New York Times took particular interest in the practice during the Depression, running no less than fourteen articles on the subject between August 1934 and August 1940. 126 In these articles, Times reporters variously referred to handlers as “Holiness,” “‘snake’ preachers,” and members of a “sect” or “religious cult.” 127 The use of this wider range of terms indicated a comparative trend in reporting that implied the practice’s similarity to other sectarian religious groups and its dissimilarity with mainstream groups. 128

… To Snake Handlers

As reporters refined their categories of religious difference, holy rollers and fanatics became snake handlers and serpent handlers. The Knoxville News Sentinel appears to be the first publication to have consistently used “snake handling” as both a hyphenated adjective and a non-hyphenated noun. 129 The Sentinel also ran a series of articles that used “Serpent-handling” to describe the practice. Many of the references in these articles place “serpent” in scare quotes, perhaps indicating that this is how the handlers self-identified or in order to highlight the implied religious distinction between snake and serpent. 130 The articles in this era frequently offered medical, anthropological, and psychological explanations for the practice. 131 The near-synonymous uses of snake or serpent handling displaced older usages as more and more reporters recognized that snake handlers were worshipers with a difference. News accounts of snake handling services slowly abandoned the association of snake handling and holy rollers and the Church of God as various pentecostal groups became more well-known and significant in American culture, although more generic terms such as holiness and cultists uneasily persisted beside the newer designations until the 1980s.

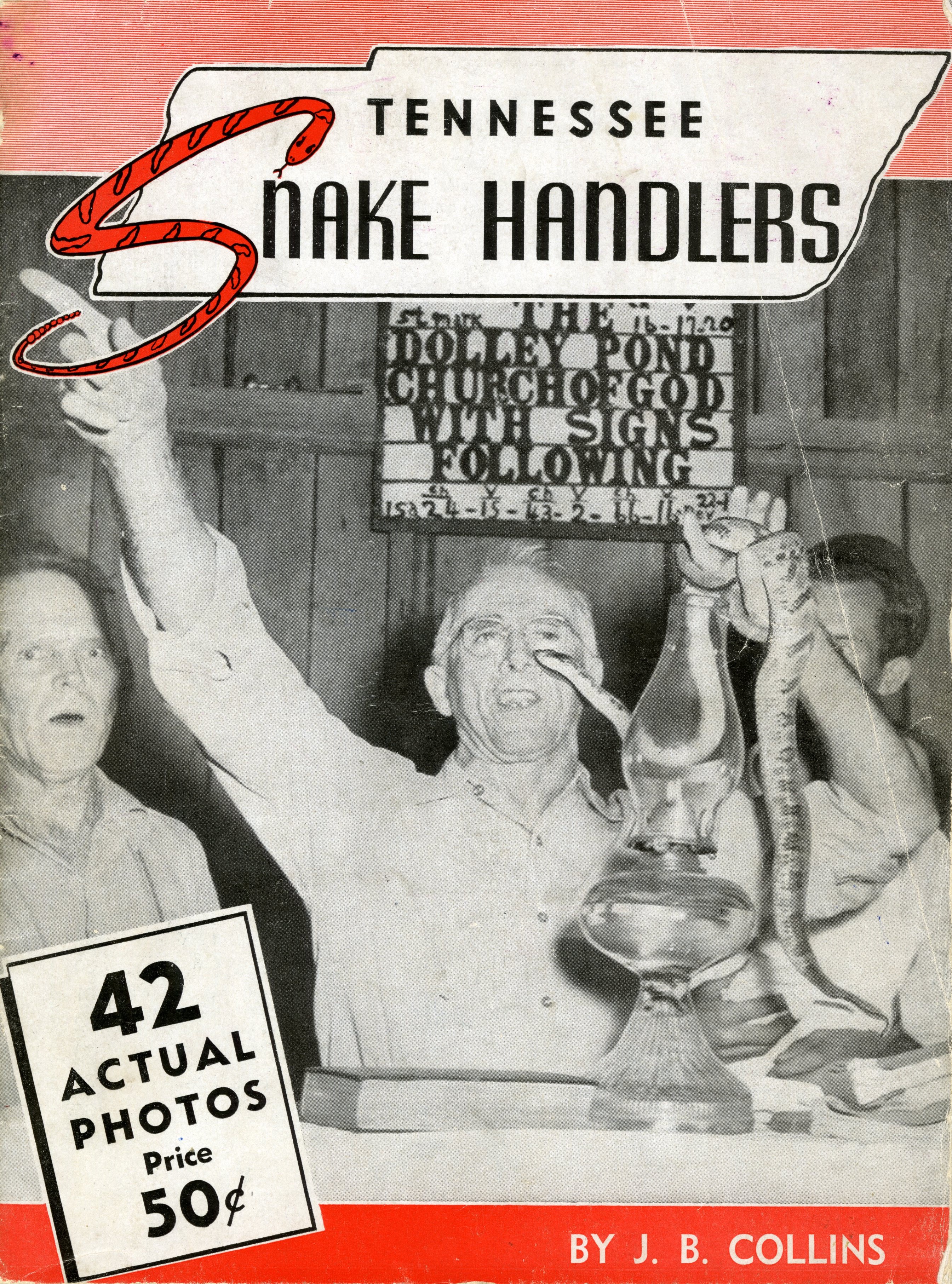

Cover to J. B. Collins, Tennessee Snake Handlers (Chattanooga: Chattanooga News-Free Press, 1947). Courtesy of Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University, J.B. Collins Collection.

The 1947 arrest of Hensley, Harden, and ten other members of the Dolley Pond Church of God with Signs Following tested Tennessee’s recent ban of snake handling leading to significant local and national coverage of the trial. Papers throughout Tennessee and the United States covered the trial, with many wire sources relying on the images and stories produced by J. B. Collins for the Chattanooga News-Free Press. Popular interest in the trial helped propagate usage of the phrases snake-handling (adjective), snake handler, and snake handling (nouns), although Collins also used cult and cultist in his reporting. This image is the cover to a 32-page booklet containing Collins’s reporting on the history of the Dolley Pond church and an account of the 1947 trial. Drug stores and newstands in Chattanooga, Dayton, and Cleveland sold the book. At the height of the trial, Collins autographed a copy for Tom Harden, an event recorded in September 11, 1947, issue of the Chattanooga News-Free Press. The book is unique for Collin’s access to the church, the vivid photos of worship services, and an in-depth interview with George Went Hensley. Collins’s interview with Hensley is one of only a handful with the preacher who would die eight years later of snakebite.

In the 1940s, the Church of God’s position on snake handling converged with these widely disseminated popular conceptions of the practice. In a 1940 Evangel article, Simmons, an elder in the church, washed his hands of the whole issue and turned snake handling over to the state. During a controversy over an independent Kentucky congregation of handlers who called themselves the Pine Mountain Church of God, Simmons rebuked the group for misappropriating the name of his church. 132 Further, Simmons wrote that snake handling was not a matter for the Church of God to deal with, but rather belonged to the secular courts:

It may seem at first that such a law banning snake handling is a violation of the Constitution but this is not true for the Constitution is founded upon the Bill of Rights and the Bill of Rights provides protection to all parties, so when people are displaying poisonous snakes in meetings they are not upholding the rights of all people. … True Church of God people will not be disturbed nor carried away with any such fanatical display as these people “snake” handlers put on for showmanship. 133

Rather than defend the sign, he argued that the serpent—the creature that caused the “trouble” and the “first break made in the beautiful order that God established”—had again caused a break and thrown the body of the Church of God into confusion. As far as the church was concerned, the handling of snakes was a dangerous expression of a corrupt secular culture of showmanship and individuality that needed to be regulated by state authorities, not by ecclesiastical discipline.

By the 1940s, the Church of God, along with many other pentecostal groups, had completed a radical transition. Under Tomlinson’s leadership in the 1910s, the church traded the rugged Unicoi Mountains for the small, but rapidly developing urban setting of Cleveland, Tennessee. With this transition, the fundamental demographics of the church’s members and subsequent converts began to change. By the 1920s and 1930s, the uneducated, poor white mountaineers who had once formed the bedrock of the Church of God—and some of its most active serpent handlers—gave way to a growing middle-class, urban-centered constituency. F. L. Lee and his successors continued the transition started by Tomlinson and eventually led the Church of God away from its rural roots. “In the years following World War II,” Crews observed, “the Church of God completed its transformation from an obscure radical sect to a church within the mainstream of conservative evangelicalism…. In the postwar years, the Church of God’s sectarianism mellowed. It repudiated snake handling…. Pentecostal worship became less emotional and less dependent on the supernatural.” 134 That such positions would have been unthinkable during Tomlinson’s overseership of the Church of God—and perhaps even under Lee’s—hardly bothered the church’s leadership from 1940 forward. The church’s shift toward urban, middle-class society and its cultivation of a less emotional form of worship that downplayed supernatural experience paralleled the rise of a new, upwardly mobile South. The moderate consensus forged between the Church of God and other pentecostal bodies rejected the ritual excesses of early pentecostal worship and led to support for the criminalization of snake handling in order to draw a clear distinction between the saints of the Church of God and the wild snake handlers of some dangerous, irreligious movement.

Conclusion